About 20 miles north of Dhanushkodi lies Katchatheevu, a 285-acre uninhabited isle born of a 14th-century volcanic eruption. Ceded in a goodwill act in 1974 by the Indira Gandhi administration to Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s Sri Lanka, Katchatheevu was the nucleus of the 1976 bilateral maritime boundary division. With the outbreak of the Lankan civil war, it became a battleground between Indian Tamil fishers and a Sinhala-dominated Lankan navy, leading to the loss of livelihoods and lives of accidental Indian forayers into Lankan territory. Sinhalese fishermen now fear that the Lankan administration might lease the island to India. But the Katchatheevu dispute’s complex, colonial legacy cannot be distilled down to parochial anxieties.

The dispute dates back to October 24, 1921, when Indian and Ceylonese delegations negotiated a ‘Fisheries Line’. The Ceylonese claimed Katchatheevu given the presence of St Antony’s Church. Once a part of the Ramnad zamindari under the Sethupathis, Katchatheevu was established in 1605 by Madurai’s Nayak dynasty. In 1767, the Dutch East India Company signed an agreement to lease it. In 1822, the British East India Company leased it from the Sethupathis. A number of leases in favour of the British government between 1880 and 1910, the judgment in the Annakumaru Pillai vs Muthupayal case (1904), a 1913 agreement in favour of the Secretary of State for India, and a 1922 report from the Imperial Records Department on the “Question of the ownership of the Island of Kachitivu [sic]” attest to India’s historic right over Katchatheevu. Yet, in 1921, the two sides informally agreed on an unratified border three miles west of Katchatheevu.

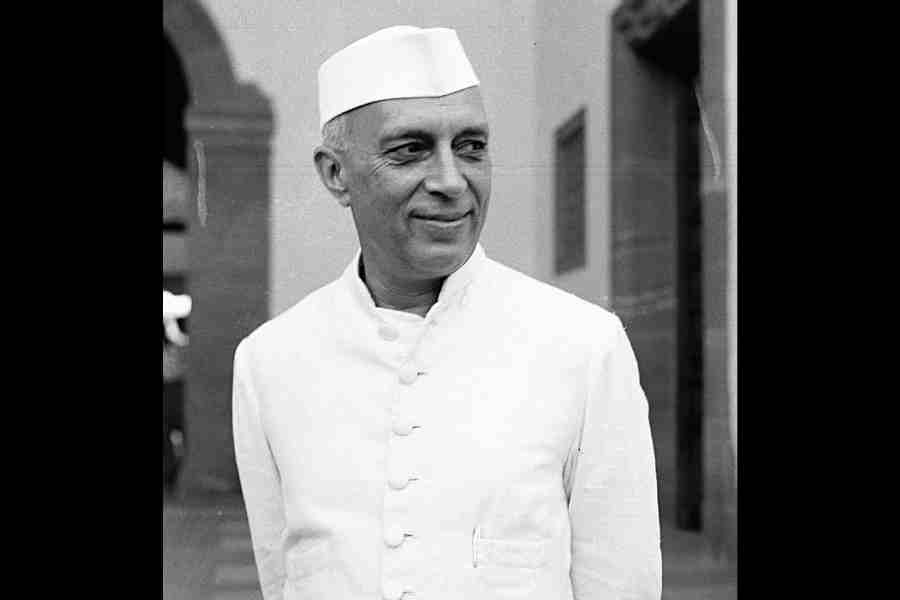

Since 1956, when India and Ceylon recognised the need for a maritime boundary, the ‘Kachcha Thivu [sic] Island Dispute’ echoed in the Lok Sabha, only to be overruled by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Ceylon, however, was adamant to enforce the principle of uti possidetis juris — colonial boundaries as postcolonial nation-state boundaries.

Katchatheevu’s geopolitical dividends swelled around February 1968 when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ceded 320 square miles of the Rann of Kutch to Pakistan, leading the Colombo-based Sun newspaper to issue an egregious newsflash, headlined, “Ceylon Government takes over Kachcha Thivu [sic].” Ceylon doggedly chased the barren island which it believed to contain petroleum deposits. Gandhi’s cession abated the three-pronged danger plaguing the Indian Ocean — Ceylon’s Sinhalese-Tamil conflict stoked in the 1970s by the Sinhalese communist group, Janatha Vimukti Peramuna; the group’s incitement by North Korean and Chinese factions; and incremental Soviet and American competitive naval deployments in the region since 1968.

However, Katchatheevu’s cession alienated Tamil parliamentarians and fisherfolk. In theory, Indian fishers retained their rights to fish around Katchatheevu — a region fertile with shrimps — though in practice they became criminal transgressors.

In 2014 — following J. Jayalalithaa’s Supreme Court petitions on Katchatheevu — India’s former attorney-general, Mukul Rohatgi, cautioned that since the island was undisputed between the two nations (but subject to a federal disagreement), India needed to resort to war to reclaim it. Given India’s restraint and ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy, a peaceful resolution lurks in new bilateral consensuses.

As Ashis Nandy once observed, Lankans “may not always live happily with the Indian state, but they seem to live happily with India’s national poet” — Rabindranath Tagore, who arguably composed the symphonies of the national anthems of India and Sri Lanka. Given its Tagorean righteousness, India will not demand the island. But Sri Lanka is in a unique position to relent over Katchatheevu’s shared administration. The extraordinary symbolic gains are inestimable in the emerging, complex global order and maritime ambitions following the G20 Summit.

Arup K. Chatterjee is a Professor at O.P. Jindal Global University