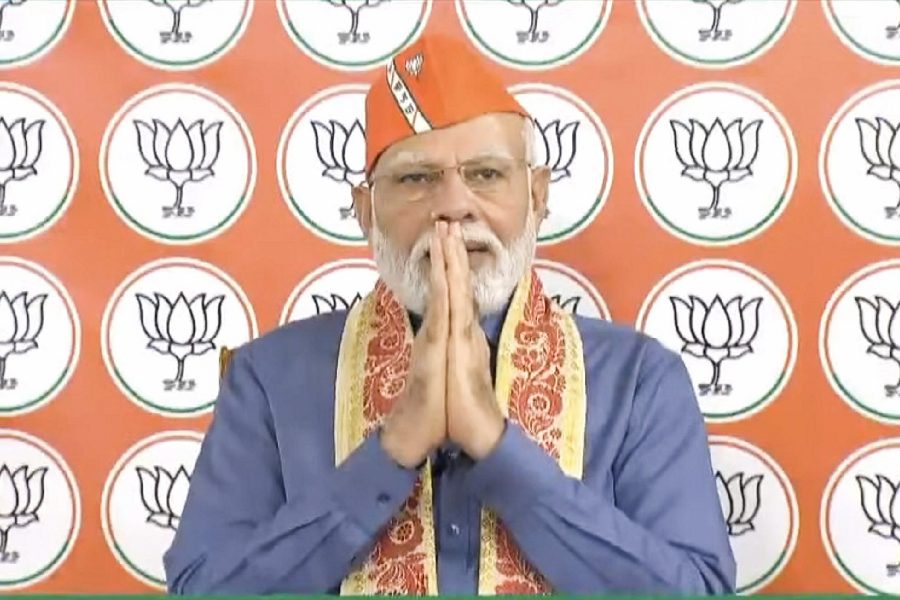

Perhaps in keeping with the spirit of freedom — India celebrates its Independence Day today — the Narendra Modi government has set itself the ambitious task of ‘decolonising’ the nation’s criminal jurisprudence. Three bills were moved in the lower House of Parliament last week that are set to replace the Indian Penal Code, the Code of Criminal Procedure, and the Indian Evidence Act and, according to the government, help expedite trials and improve conviction rates, among other improvements. The Union home minister has made an earnest case for reform. A jail term has been introduced for hate speech. This was perhaps necessitated because of the communal fires that are being lit in New India with provocative speeches made, more often than not, by leaders or supporters of the Hindutva brigade. It remains to be seen whether the stiff punishment for hate speech — not quite a novelty since Section 295A of the IPC has similar provisions — serves as a deterrent given the impunity enjoyed by the mischief-mongers. Lynching and gang rape, two other warts that New India has sprouted, have also been met with stringent punishments. The outcome of these punitive interventions, too, would depend on the political will to act against these transgressions. There is the possibility of harsher sentences for rash driving and sex on the false pledge of marriage. This thrust towards judicial retribution should not ignore the grey areas concerning consent in the case of the latter.

For all the claims of breaking new ground, the government seems to have developed cold feet on some key aspects that merit reform. Marital rape, to cite one example, remains unaddressed. Reform is not a simple matter either. The removal of unnatural sex as an offence under the new penal code may have been a necessary step to strip law of its cloak of colonial puritanism but it is bound to raise other troubling questions: should, for instance, an assault on a man by another using coercion not be considered an offence? This goes to show that the bills in their present form need to be subjected to scrutiny and deliberation. But is this government, a votary of muscular politics, amenable to scrutiny?

The case for further discussion and, hopefully, amendment of the bills is augmented by the concern that the regime is attempting to peddle reform in the guise of a legislative continuum that is inimical to the democratic ethos. Section 150 of the Bharatiya nyaya sanhita bill, it is feared, would be a perfect successor to the dreaded law on sedition. Similarly, the new, ambiguous definition of terrorism could well impair the right to protest, a core tenet of a democratic polity. Irony — the oxygen for creative arts — falls under the shadow of defamation. It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that the bills are a reliable reflection of Mr Modi’s grim, authoritarian regime. The truest testimony of reform would be a government’s willingness to desist from weaponising laws to meet ideological or political ends. The proposed legislations fail on this count.