A Chennai-based startup inaugurated India’s first private space pad at Sriharikota. This development came close on the heels of the launch of Vikram-S, India’s first privately developed rocket. These occasions are significant milestones in India’s storied space odyssey. They also present us with an opportunity to ponder the implications of continued private sector involvement in space activities.

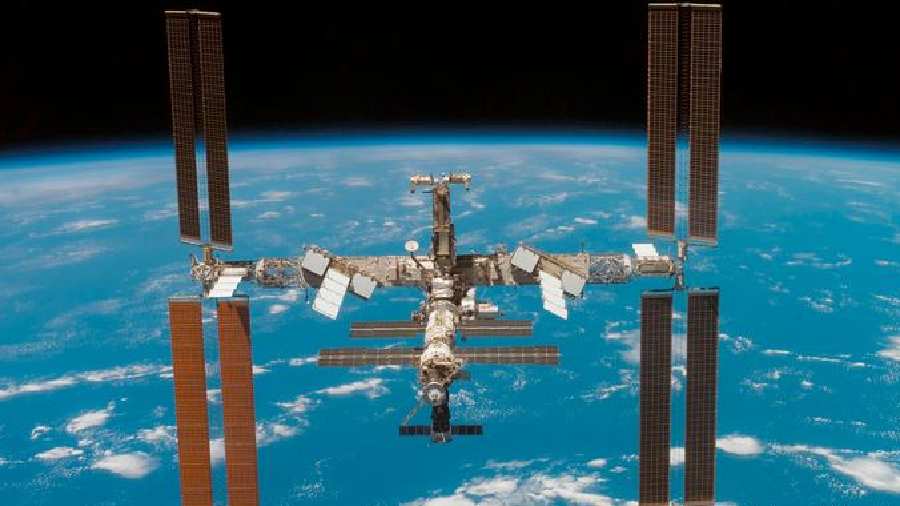

One of the most pressing problems plaguing the international comity of spacefaring nations is that of ‘space debris’ proliferation. The Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee defines space debris or space junk as any human-made space object or its constituent part(s) that have become non-functional after serving its intended purpose in the space activity. At present, there are around 70 national and regional space agencies, with over 13 spacefaring nations having independent launch capacity. With the increasing commercialisation of space for weather forecasting, surveillance, telecommunications and so on, traffic congestion in outer space will lead to a commensurate increment in the risk of damage to person or property as a result thereof. In August 2022, space debris purportedly from SpaceX crashed in an Australian farmland. This was preceded by reports of Chinese space debris falling into the sea in the Philippines.

Currently, as per Nasa, there are upwards of 27,000 pieces of trackable space junk in near-Earth space. The precise concern is that if left unregulated, continued contamination of outer space may pose a challenge to the very idea of outer space as a global ‘commons’. To stem the degradation of outer space environs, space has been considered to be the Common Heritage of Mankind in international law. Taken holistically, CHM encompasses the principles of ‘no harm’, ‘polluter pays’, and ‘sustainability’, among others. The utility of these principles lies in strengthening the ingredients of inter-generational equity and long-term sustainability into international governance ofspace.

Eventually, through legal osmosis, these principles found their way into the fabric of Indian space law. India is a signatory to the UN Liability Convention, 1971, as a result of which India bears international responsibility for any space object it launches from its territory or for any space object which use sits facility. Such responsibility was sought to be concretised in the draft space activities bill 2017, which was touted to be the foremost national legislation for commercialisation of space and the opening up of the sector for private players. The same has been gathering dust; yet, it must be noted that Section 8(2) of the 2017 bill imposed a ‘no harm’ obligation on all license holders. It did so by mandating that all commercial space activity license holders carry out their space activities in a manner so as to avoid contaminating outer space or polluting earth’s environment.

The push towards incorporating the principles of ‘polluter pays’ and ‘sustainable use’ was further buttressed by Section 16 of the2017 bill, which sought to impose a maximum penalty of three years imprisonment, or an uncapped monetary fine starting at one crore (or a combination of both imprisonment and fine), for causing damage or pollution by space activity. Such legislative drafting was consistent with the Indian position of sustainable use of outer space.

To continue its leadership as a space-faring nation, the management, mitigation, and remediation of space debris should form a larger, more vocal, part of India’s space vision in the 21st century. In this regard, India can ensure sustainability through a few practical ways such as advocating for fixing debris quotas, levies, or timelines for debris clearance as well as exploring new methods to extend the operational lifetime of functional space objects. The need of the hour is for erring nation-states to adopt the aforementioned principles and translate them into State practice as a means of governance of outer space. This will serve as a bulwark against continued contamination of outer space commons.

Sushant Khalkho is a lawyer