China has launched a concerted charm offensive aimed at shoring up its influence in Southeast Asia amid fears that India and Japan are making significant inroads into the region, especially in Myanmar. It is also part of a pre-emptive strike in readiness for expected changes in US policy towards Asia by the Joe Biden administration as well as for the changed regional environment and economic recovery needs in a post-Covid era.

The Chinese diplomatic assault not only poses problems for the three informal allies — Japan, India and the United States of America — but also creates tensions within the regional bloc, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, over bilateral and multilateral relations with Beijing on a number of fronts: strategic, economic and cultural. Much of China’s strategy centres around what diplomats are describing as Covid or vaccine diplomacy. But it is also concerned with Chinese and regional security, stability and interconnectivity. Beijing has a proprietorial attitude towards this since it regards Southeast Asia to be its backyard. Although it may not want to exert direct control over the region, it does not welcome foreign influence or interference — it deems Indian, Japanese and especially American involvement as such — in these countries. So Beijing has reacted strongly to what it perceives to be trespassing in its domain. One of China’s biggest concerns is the control of maritime cooperation and shipping lanes from the Indian Ocean around the Asian archipelago to Shanghai and China’s eastern sea border.

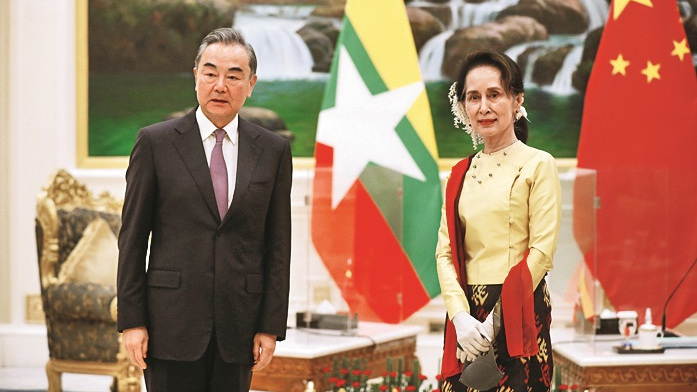

Myanmar, which straddles South Asia to the west and Southeast Asia to the east, is central to this diplomatic drive to strengthen Beijing’s influence. China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, is heading Beijing’s blitz in the region: he recently made a critical visit sometime ago to key parts of Asean — Myanmar, Indonesia, Brunei and the Philippines — on his way back from an important tour of Africa. This trip follows his visit three months ago to the other countries in the regional bloc: Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. Noticeably, he is yet to visit Vietnam as part of this surge.

But Beijing’s biggest concern is its position in Myanmar, and Wang Yi started his most recent thrust into Asean with an important two-day trip to Myanmar’s capital Naypyidaw. It was intended to further consolidate Chinese influence in the country, which has become increasingly dependent on China since Aung San Suu Kyi was swept to power in the 2015 elections. However, Beijing has increasingly become alarmed at the changing international dynamics in the region: principally the deterioration in relations with Delhi since the middle of last year and Tokyo’s aggressive and concerted push into the region, especially in Myanmar over the last 12 months. And now, there is the prospect of Washington re-engaging with Asia after four years of neglect during Donald Trump’s insular and idiosyncratic approach.

Officially, Wang Yi’s primary purpose on this Myanmar visit was to show China’s unswerving support for the country and its civilian leader, the State Counsellor, Aung San Suu Kyi. But foreign diplomats believe that Naypyidaw was extremely reticent about the timing and the purpose of the visit, which was seen to be part of ‘vaccine diplomacy’. Wang Yi promised a gift of 300,000 doses of China’s CoronaVac vaccine, which is expected to be delivered within the next few months. China’s donation came on the heels of Myanmar’s deal with India to buy some 30 million doses of an Indian-produced vaccine, according to the president’s spokesman, Zaw Htay. The government has already paid US $75 million upfront or half the amount as a deposit. Covishield is produced by the Serum Institute of India, the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer, and developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca. The first batch of 1.5 million doses arrived in Myanmar recently. Indian officials say that this consignment is, in fact, a donation in the spirit of mutual cooperation under the Indian government’s ‘Neighbourhood First’ and ‘Act East’ policies.

This vying for influence using the Covid vaccines represents a microcosm of the competition between the two regional rivals. Western diplomats believe Beijing may be upset that Myanmar has turned to India first for the vaccine instead of China. This has put a significant dint in China’s planned diplomatic offensive.

On his recent foray abroad, Wang Yi has been promising support to combat the countries’ fight against the pandemic and in their post-Covid recovery. Almost all countries in the region have accepted Beijing’s offer of vaccines, to a greater or lesser extent, albeit with increasing reticence amongst most government’s in Asean. Myanmar, for example, is planning to get the supplies of the vaccine from several sources, including India, Russia, the United Kingdom and China.

On his most recent visit, the Chinese foreign minister met President Win Myint, the State Counsellor and the Commander-in-Chief, as is his usual protocol. But the latter meeting was perhaps the most critical for there are growing concerns in Beijing that Myanmar’s military is veering away from their previous cozy relationship and leaning towards Russia and India. There is also concern that the Biden administration may resume US-Myanmar military cooperation. While the recent acquisition by the Myanmar military of a submarine of Indo-Russian make may not pose too many problems, it is seen as a significant reflection of Myanmar’s military’s pronounced tilt towards the West in general and a preference for Indian and Russian equipment in particular. The symbolism of these submarines has also alarmed Beijing whose overall strategic objective in the region is to ‘command’ the shipping lanes and develop transport and communications interconnectivity throughout the region to access sentinel points. China has already built or is in the process of building ports and naval bases in the Philippines and Cambodia which are part of the planned network.

The key concern is Myanmar. Beijing has already secured the most important shipping base in Western Myanmar — Kyaukphyu in northern Rakhine — which would give China unfettered access to the Indian Ocean besides offering a significant trading route linking it to South Asia and the Middle East. China also has a strong foothold in the Yangon port, and there are tentative plans to rebuild the port at Mawlamyine, south of Myanmar’s commercial capital. The possibility of building a port in Myeik, further south on the Andaman Sea, is being explored. This would provide an access point to southern Thailand.

But Japan and India have frustrated Beijing’s hopes of securing the full-maritime encirclement of Myanmar. India and Myanmar are working on opening the Sittwe port in the Rakhine, north of Kyaukphyu, in the next few months. The port is part of the Kaladan multi-modal transit transport project, which Delhi hopes will function as India’s gateway to Southeast Asia. Further south and adjacent to Thailand, the Japanese have beaten off Chinese interests in the Dawei special economic zone and its planned port, much to Beijing’s chagrin. In Bangladesh, Japan is building the Matarbari deep-sea port, close to Cox’s Bazar, to complement Bangladesh’s main trading port and entrepôt at Chittagong after the plans for a Chinese-backed port at Sonadia were cancelled late last year.

There is a battle brewing over patrols and safeguarding shipping lanes in the Andaman Sea and the Indian Ocean. China fears that Myanmar has opted for an Indo-Russian option for sea security. Indian and Chinese submarines need qualitatively different naval base facilities for docking, refuelling and repairs. So Myanmar’s acquisition of a second-hand Indian submarine and the Tatmadaw’s pending order for more Russian vessels mean that its strategic choice is incompatible with Chinese equipment. More ominously, it points to a possible naval arms race around the Indian Ocean as Delhi must prepare to confront China in its own backyard.

The author is a former BBC World Service news editor for Asia and is based in Myanmar