India has overtaken China as the world’s most populous country, according to the United Nations. The bulk of Indians are skewed young — there are more workers than retirees — and the workforce will continue to grow until the mid-century. This is economically significant: an expanding workforce can produce more with existing capital and technologies, which is why it’s called a demographic dividend. Commentary has, therefore, focused on realising this. The common thinking here is that this is achievable through large-scale manufacturing that can absorb the vast and unskilled rural labour surplus, preferably by attracting foreign capital into the exporting sector to increase productivity and by investing more in human capital to improve the quality of the workforce. The inevitable comparison here is with China, the longest, continuous example of rapid economic growth based on manufacturing exports.

India does share with China many of the initial attributes that favour growth. For example, it has one of the largest populations and workforce in the world as well as a low-wage labour market. Its size, location, an increasingly strategic role, a valuable economic potential in terms of scale and agglomeration of production, the capacity to create public goods, are the other features that support growth. Now that China’s population has peaked, its workforce is declining for a decade, its workers are earning more each year, and multinational firms based there are seeking alternative places, the belief is that India could exploit similar gains through a China Plus One strategy. To that end, Indian policy provides pointed incentives to boost manufacturing-driven exports at a global scale.

This is combining with good luck: geopolitical reconfigurations prompted by the pandemic and Russia’s war with Ukraine that favour India in significant economic aspects. The equation has further changed with the global location dynamics of multinational corporations, especially those in the United States of America, and some supply chains inclining towards India. The foremost example of this is Apple’s partial shift out of China to India, amongst other countries. These rearrangements raise hopes of prospective replication in other products. The question to ask then is that were India able to address all its human and physical capital deficits and attract mega firms and foreign direct investments into the tradable sector, would it be able to grow the China way? Or could it? Maybe, yes. More likely, maybe not.

Comparisons sometimes overlook the underpinnings of China’s export-led success. The roots lay in a long stretch of wide-ranging economic reforms starting in the 1970s. The fundamental changes specifically aimed at accelerating the country’s growth rate by increasing productivity and improving the allocation of resources. Briefly, the transformation began with the semi-privatisation of its communal farming which incentivised private agents to increase productivity and growth in agriculture that employed most of the workforce at the time. Rural households were allowed to plough their savings into local businesses, manufacturing, and transport to foster private enterprise. Progressive trade liberalisation to increase labour productivity followed. Initially, this limited foreign direct investment to special export zones with subsequent relaxations. This was followed by the easing of rules and regulations, fiscal reforms to raise tax revenues and strengthen the public balance sheet, and the opening of financial markets.

Much of these reforms occurred before China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, before which it managed to double its decade average export growth in the 1990s over the 1980s, according to the International Monetary Fund. Formal integration with the world trading system uplifted this far more, helped further by its deliberate exchange rate undervaluation for extra competitiveness to secure markets by unfair means. However, earlier reforms of the past enabled strong backing from macroeconomic policies. For example, the ability to control inflation, especially food inflation, through successive increases in cereal crop yields from the 1990s (after an outburst in the late 1980s) provided greater manoeuvring possibilities in monetary policy. Healthy tax revenues, prudent spending, and moderate debt provided complementary fiscal policy abilities, including the accumulation of persistently large current account surpluses. Careful capital account liberalisation at much later stages and avoiding external financial disruptions and asset price shocks were the other elements.

This is not to say that all has been hunky-dory with China’s growth strategy. The aftershocks from its macroeconomic distortions resulting in significant imbalances have proved difficult to rectify despite a decade’s attempt to rebalance from exports and investment towards consumption or domestic demand. Reversing its one-child policy to counter demographic change has met with little success too.

The point here is to highlight the vacuum in fundamental economic reforms that are either missing, or have been delayed, or are partial and incomplete, in India’s case. In some respects, these are very recent, and will take time to settle down. This deficit is sometimes overlooked in the discourse that mostly focuses on our past failures to pursue export-led growth in the 1950s and 1960s. In the delayed catch-up to exploit China’s retreat and structural export shift, the absence of structural reforms in key areas is important to reckon with.

Two sectors — agriculture and public finances — continue to make India’s macroeconomic framework vulnerable. These also restrict policy space that would otherwise be freer to support growth. Illustratively, inflation, especially food prices, has remained a recurring challenge; managing it squeezes monetary policy space. Fiscal deficits are persistent and structural; public debt rises periodically in relation to national income whenever growth slows. As a result, public investments in physical and social infrastructure are limited, and are often cut when constraints are binding. Resources and costs for the private sector are affected too.

This is not to undermine the abovesaid factors favouring India and the positive augur for harnessing the demographic boon in the forthcoming years. It is quite possible that further unexpected changes in the international arena and other elements and sources may help overcome these deficits, catapulting growth with sufficient strength and sustenance. That could build up the health of public balances, allowing opportunities to implement structural reforms that are difficult when economic conditions are not conducive. For all we know, reaping the population bonus may be faster than slower, providing more macroeconomic policy strength than expected. Time will tell.

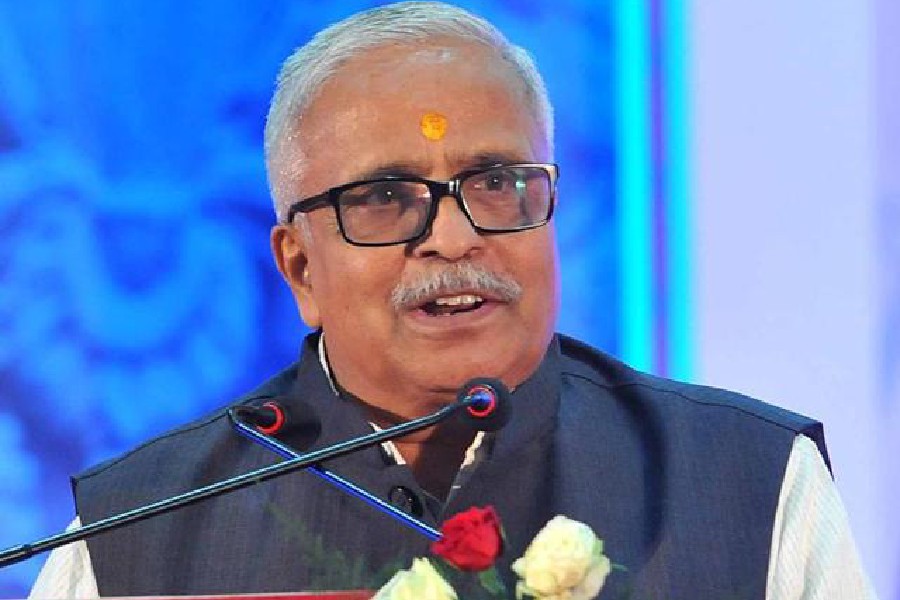

Renu Kohli is an economist with the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, New Delhi