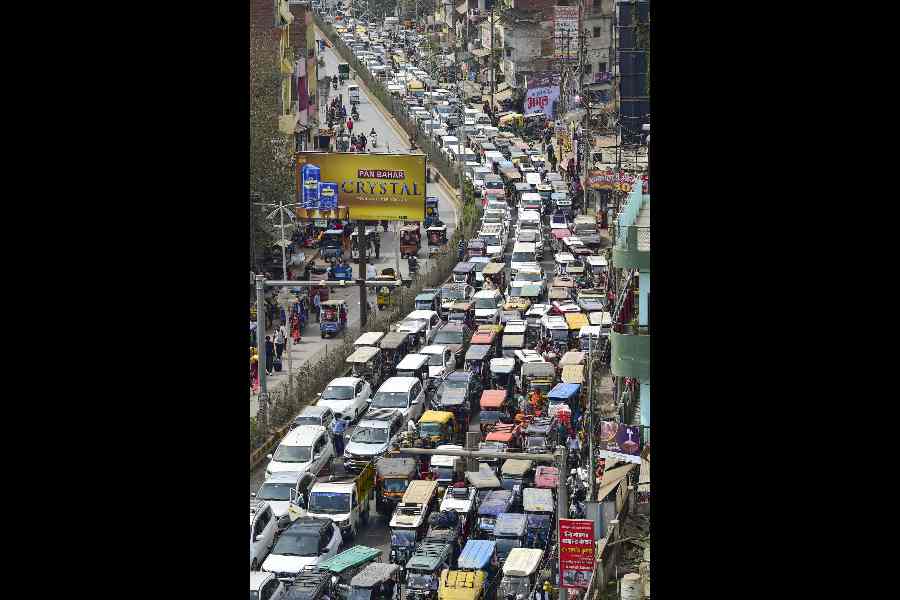

Between the years 2014 and 2023, the number of Indians who perished in road crashes was higher than the population of the Union territory of Chandigarh and near equivalent to that of Bhubaneswar. The data make for sombre reading. An estimated 15.3 lakh citizens died in road accidents in the last decade; the decadal fatality figure for 2004-2013 was 12.1 lakh. There, thus, has been a worrying rise in such fatalities. Road deaths, the road transport ministry says, in the country number around 250 per 10,000 kilometres. The corresponding figures for some other countries, such as the United States of America, China and Australia, are as follows: 57, 119 and 11, respectively. This is not to say that deterrents are not in place. Provisions under the Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Act, 2019 include measures to ensure road safety. Stiffer penalties for traffic rule violations, the impounding and the suspension of licences in cases of overspeeding, dangerous driving, drunk driving, use of unsafe vehicles and so on, driver refreshing training course as a remedial measure as well as automated testing for fitness certification are among these provisions. The spectre of road deaths has even led to interventions from the highest court on occasions. Yet, blood continues to spill on India’s roads.

A strange set of reasons has been cited to explain the rising mortality. These include a rise in population, an increase in the length of roads, and an uptick in the number of vehicles. Government sources suggest that the number of registered vehicles has more than doubled, jumping from 15.9 crore in 2012 to 38.3 crore in 2024. The length of road networks has risen too, from 48.6 lakh km in 2012 to 63.3 lakh km in 2019. But the more potent causes of road accident deaths are unlikely to be found in these developments. There is a line of thought that suggests that the lack of coordination among multiple sectors is the real cause: road fatality, after all, is a multi-sectoral phenomenon. The lack of the demand for accountability from officials, unlike in the case of, say, murder, has also led to institutional indifference. The policy response to these loopholes must be comprehensive. Otherwise, India’s roads would remain killers.