Over the last week, the British government has made it clear that it plans to unilaterally modify the Withdrawal Agreement it signed with the European Union. Briefly, the Northern Ireland Protocol in the agreement specifies that goods shipped from Britain to Northern Ireland are subject to customs checks to ensure they conform to EU regulations. This is important because otherwise there would have to be customs checks along a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic. It would undo the achievement of the Good Friday agreement: a borderless island, at peace with itself. Boris Johnson has now tabled a law that would give it the right to waive customs checks and duties without reference to the EU in the event of no deal. His government acknowledges that this would be a breach of international law but argues that it is essential to preserve British sovereignty.

How is this local European squabble relevant for the rest of the world? Johnson’s infringement of international law is trivial in itself but revealing in a historical way. Britain and the United States of America designed the norms and institutions of the world order after the Second World War. Much of the pearl-clutching by Johnson’s critics, within the Conservative Party and outside it, has been provoked by the spectacle of Great Britain, the inventor of modern international law, explicitly reneging on its international obligations. They are appalled by the reputational cost of this move, by the practical damage in terms of other trade treaties that Britain hopes to negotiate but most of all by the loss of the moral high ground in international affairs.

Britain’s global edge has always been its talent for first writing the letter of the law and then finding the words to stay on the right side of it. Put another way, Britain’s genius for sublimating self-interest into legal, political or economic principle has been the envy of the world for two centuries. This is why Johnson’s cheerful owning of illegality is properly demystifying.

From the Opium Wars of the 1840s, through the unequal treaties imposed on subordinated countries, down to the invasion of Iraq, the Anglosphere has successfully spun gunboat diplomacy into international law and illegal invasions into just wars. When I studied modern Chinese history at university in the Seventies, the standard textbooks had titles and chapter headings that set the subordination of China in a modernizing frame. When Britain forced Indian opium upon China, it did so in the name of free trade. ‘Tradition and transformation’ and the ‘opening of China’ told a story in which Western gunships figured as China’s unlikely bridge to modernity.

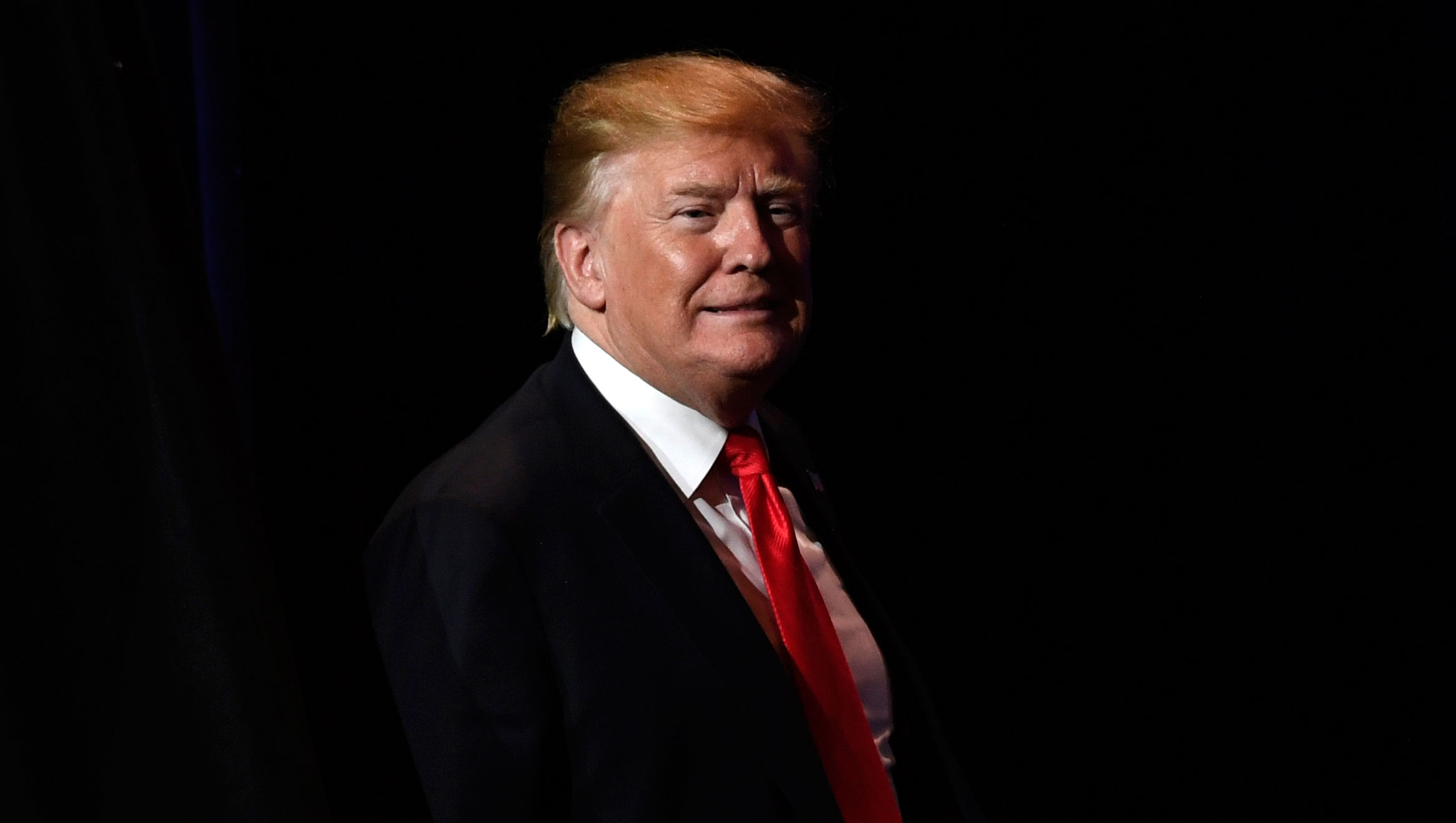

The international order, free trade, the rule of law — the ability to use these mantras to the Anglosphere’s advantage was predicated on political, military and economic hegemony. The rise of Johnson and Trump and their explicitly rule-breaking brand of politics is significant as a symptom of a shift in the global balance of power.

The outrage about Johnson’s move suggests that walking away from solemnly signed international agreements is unprecedented. This is unhistorical and untrue. Two years ago, Donald Trump withdrew the US from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, otherwise known as the Iran Nuclear Deal. This was a deal, which had the imprimatur of the five permanent members of the United Nations security council, plus Germany and the EU. The monitoring mechanism of the deal certified repeatedly that Iran had complied with its obligations but Trump declared that the deal was ‘horribly’ lopsided and walked away from it. The other signatories made plaintive noises but did nothing to buy Iranian oil or ease the punitive impact of Trump’s harsh sanctions. Having reneged on the agreement, the US insisted that Iran was bound by it and even tried to bully the UN into imposing sanctions. This provoked nothing like the indignation occasioned by Johnson’s nibbling at the Withdrawal Agreement. And if the withdrawal from the JCPOA is justified as it sometimes is on the grounds that it hadn’t been ratified by Congress, it’s worth remembering that the US withdrew from the Senate-ratified ABM treaty because George W. Bush wanted a shiny new missile that its terms forbade.

Johnson’s re-writing of the withdrawal treaty provoked outrage for two reasons. First, owning the illegality of the new law was seen as an unforced error by his British critics. In their view, Johnson should have found a form of words, a fig leaf, to deflect the charge of law-breaking. The second reason for outrage was that Great Britain was doing this to a bloc of other European countries; not China or Iran or Mauritius.

Boris’s unilateralism, his two fingers at the EU, was outrageous because he was blowing off Western trading partners. Had he done something similar to Turkey or India, there would be some tut-tutting because dispensing with necessary hypocrisy is always deemed unwise, but no one would be talking about a fatal blow to Britain’s standing in the world.

We don’t have to speculate about the likely difference in reaction; there are concrete examples available. So long as China didn’t threaten the economic or technological supremacy of the US, the Western world and its public opinion were happy to acquiesce in the rise of China as the world manufactory. The moment China became a real rival and incubated hardware and software behemoths of its own like Huawei and Byte Dance, the rhetoric of free trade and global capitalism was binned and Trump intervened to blunt China’s 5G advantage and to force a distress sale of TikTok so that Microsoft or Oracle could buy it cheap.

It is not a coincidence that Britain and the US today are defined by Johnson’s Brexit and Trump’s project to make America great again. Their explicit hostility to international obligations that constrain their populist agendas is a function of decline. Their countries never wholly recovered from the Great Recession and the continuing rise of China over the past dozen years prompted them to disengage from an international order that they no longer dominated. Their shambolic response to Covid-19 and its spread was the coup de grâce. Trump’s withdrawal from the WHO in the wake of the pandemic, accusing it of whitewashing China, and Johnson’s pursuit of a hard, no-deal Brexit are the latest examples of this increasingly disorderly disengagement.

It is clarifying that these two men should preside over this time of Western decadence. Johnson is a clown and Trump a huckster, but their narcissism makes dissembling impossible. This is what the Anglosphere looks like when it’s home and not pretending: old, overwhelmingly white people, gathered around blow-dried blond fantasists who promise to turn a fading dominance into go-it-alone glory.