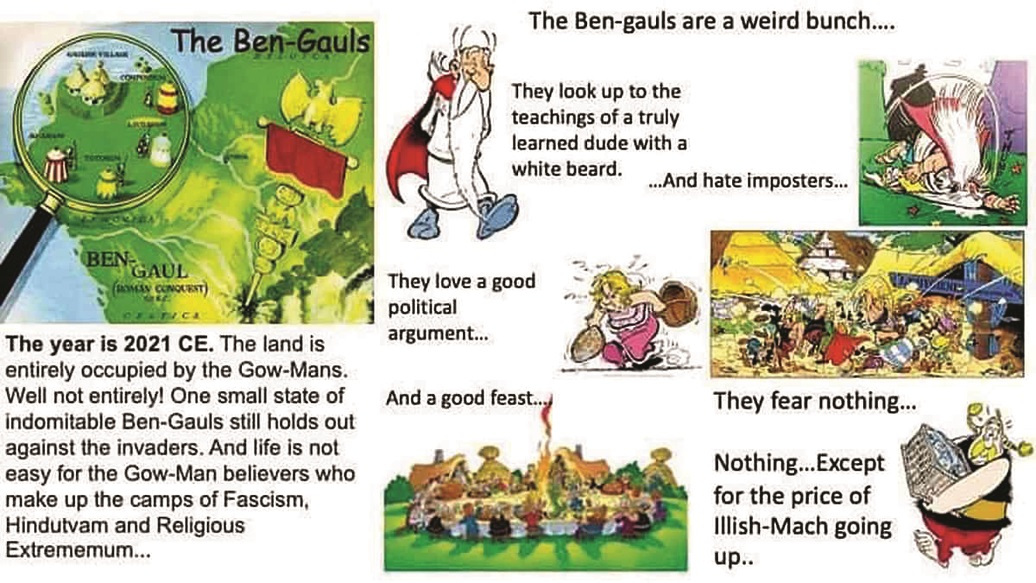

There was a cartoon doing the rounds on our phones soon after the election results in West Bengal modelled on the Asterix comics. Superimposed on the original drawings of the first page of every Asterix comic, we saw Gaul now renamed “Ben-Gaul”, accompanied by a tweaked text that read: “The year is 2021 CE. The land is entirely occupied by the Gow-Mans. Well not entirely! One small state of indomitable Ben-Gauls still holds out against the invaders. And life is not easy for the Gow-Man believers who make up the camps of Fascism, Hindutvam and Religious Extrememum...” Then the characters were introduced under the heading: “The Ben-gauls are a weird bunch...” A character resembling the village druid, Getafix, was shown strolling along — “They look up to the teachings of a truly learned dude with a white beard...” — followed by him tripping on his beard to land on his head in the next frame, where the narrative continues “... And hate imposters...” Other scenes, typical to the pages of an Asterix comic book, were captioned: “They love a good political argument...”, “And a good feast...”, “They fear nothing...”, ending with “Nothing... Except for the price of Illish-Mach going up...”

This was just one of many jubilant images, lines, poems, and paragraphs journeying from phone to phone after May 2. Lines such as “Humpty Dumpty came to Bengal/ Humpty Dumpty had a great fall” circulated among like-minded, mostly middle-class, people in the city. This euphoria, this pride in Bengali exceptionalism, the congratulatory messages from other regions of India for Bengal having stopped a juggernaut were, and should be, deeply worrying to the onlooker.

The worry is not only that a right-wing party has, for the first time in the history of Bengal, won so many seats in the Vidhan Sabha — certainly the numbers should make anybody pause and think. If the Opposition were wise, it would tell its spokespersons to be quiet about its massive gains and build upon the base now created here with their heads down — it would be the best way to consolidate and creep up surreptitiously with a mammoth presence in five years. The worry is also not related to the actual powers of resistance ‘Ben-gaul’ has in comparison to Kerala, which has done a much better job of keeping right-wing intolerance at bay, so that one can remain fairly confident that no major inroads will be made in that state at least in the near future. The deep and abiding concern is, rather, to do with who will have the last laugh if (or when) the sectarian poison now injected into the cultural bloodstream of Bengal begins to act upon all that vaunted exceptionalism.

Unlike anywhere else, the battle for Bengal in the local and national media was high profile and high decibel, and one of the key tropes against the ‘outsiders/invaders’ was Bengali cultural pride. But how long can the cultural past be invoked to fight present battles? How long will Rabindranath-Ramakrishna-Vidyasagar help the Bengali middle classes — the much-revered and then much-reviled bhadralok — hold their heads above the water? Not that they matter in electoral terms. As any middle-class citizen of the state knew growing up in the thirty-four years of Left-ruled West Bengal in the city of Calcutta and then Kolkata, it is not they who decide. Election results showed, again and again, through the 1980s and 1990s, that it really didn’t matter what the Asterix- and Tintin-reading public thought or who they voted for. This much we all know even now: that this Feluda-obsessed urban bubble did not win Bengal these elections. What then has been their role historically — what exactly is the nature of their contribution to Bengal?

Any one-dimensional answer to such a large question would fail to do it justice. Yet one could point out, first of all, that the state had always had an advantage educationally in comparison with the rest of India till the 1970s. Conventionally, it is from the colonial era onward, it is thought, that education has been prized by the people of Bengal. A famous account exists of poor boys running behind the palanquin of David Hare (as also of Reverend Duff) pleading to be admitted to his school where he sponsored so many for a free education at the Hindu College if they had merit. But the Hindu College was not built on hot air — without the involvement of the entire province, it would have floundered on a seedbed of privileged Calcutta family scions alone. Detailed colonial reports — especially and most famously Adam’s Reports of 1835 and 1838 — record that pathshalas, tols and madrasas were present in great numbers throughout the region from the pre-colonial period, and that most families in the villages (not just the upper castes) sent their sons to school. A close look at Anathnath Basu’s 1941 Calcutta University Press edition of the Reports themselves (commissioned by William Bentinck but unused by Thomas Babington Macaulay, who wrote his Minute without recourse to this data) shows that William Adam, friend to Rammohan and Bengali speaker, travelled extensively across Bengal and concluded that government support for these rural schools and seminaries should be used to reinforce this traditional base: learning would then spread wider, faster and better than an English education perhaps could.

History took a different turn at that moment, but this is not to say that somehow all that followed from that ‘English education’ was poison fruit from Macaulay’s poison tree, as Samar Sen put it in “Pancham Bahini”. It is only to assert that it is through a return to grass-roots education and a huge investment in schools, colleges, infrastructure and teaching that one can imagine a way of stopping, even if in the long run, the inexorable march of sectarian politics in the state. Serendipitously in alignment with this thought, Mamata Banerjee has announced at her first cabinet meeting itself that the government will set up an English-medium school in every block of the state — addressing a perceived rural demand which has led to a mushrooming of English-medium private schools in the districts. This could be a step in the right direction, although one immediately wonders where those schools’ teachers are to be found and what their level of proficiency might be. In order to address those questions, it might be wise, therefore, to supplement this ground-level task with the shoring up of every higher-education institute in the state. To set up schools, one needs schoolteachers. The average Bengali may have heard only of Ramtanu Lahiri, but Parimala Rao has shown in Beyond Macaulay that far from it being the case that graduates of the Hindu College rushed en masse into lucrative government jobs, records show that many of its students went on to take up jobs as teachers throughout the province.

The minister for education does not need telling, certainly, that however depleted West Bengal may seem in terms of its former glory, enough survives that could still be put to use. World-class academics, scholars, researchers and teachers still populate the higher echelons of education in the city — all that is needed is an unbiased, non-partisan, and wholehearted commitment from the government for them to function to their full potential.

Rosinka Chaudhuri is Director and Professor, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. Views are personal