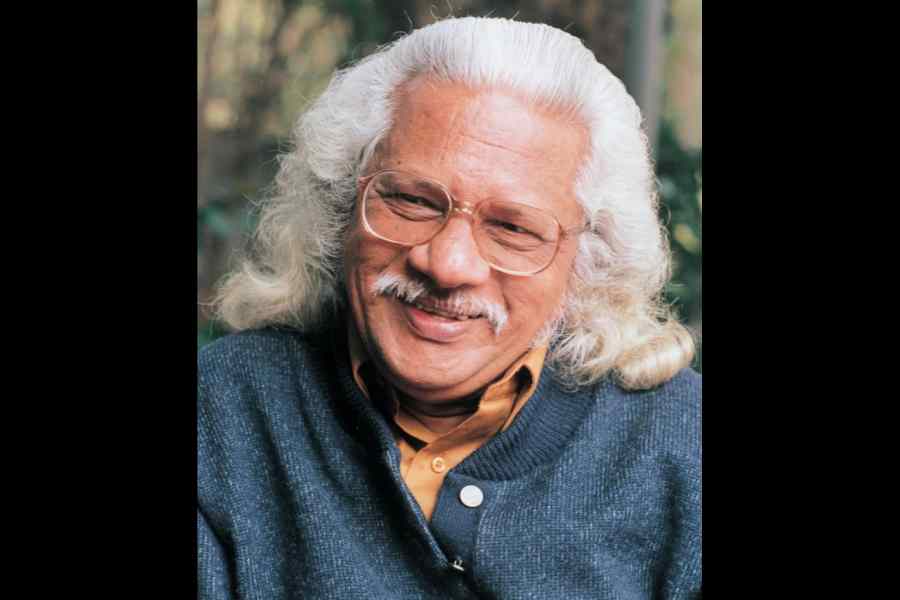

Adoor Gopalakrishnan, who turned 83 earlier this month, now reminds one of his unforgettable characters, living in the liminality between the past and the present. Since the demise of his wife, Sunanda, in 2015, the maestro has lived alone in Darsanam, his exquisite wood and granite house amidst a coconut grove on the outskirts of the city of Thiruvananthapuram. A showpiece of traditional Kerala architecture, Darsanam was recreated by Adoor in 1977 using the parts of a two-centuries-old tharavadu (haveli) dismantled by owners to make way for a moviehouse and auctioned as fuel wood and scrap. Adoor bought and shifted the entire house, stone by stone and wood by wood, and rebuilt it in its present location even more gracefully. As in the master craftsman’s films, in which dwellings are as critical as the characters, light and shade play hide and seek in Darsanam, with the copious Kerala monsoon welcomed into its inner courtyard. One recalls the leitmotifs in his oeuvre: eviction and dislocation, the search for identity and home.

This writer has been coming here for years to meet Adoor and adore his house. Neither age nor loneliness appears to have affected his spirit. A consummate chronicler of the past, he engages with the present with equal ease. His debut film, Swayamvaram (1972), was one of the earliest Indian movies to have synchronised sound recorded with a Nagra, the Swiss-made portable recorder that revolutionised outdoor film-making. His last, Pinneyum (Once Again, 2016), a thriller, was his first film shot digitally. The octogenarian showed me a cute short video he recently shot with his Samsung mobile phone.

Adoor is upbeat that Malayalam cinema has now emerged as the country’s biggest grosser, breaking language barriers. “After Pinneyum, I had resolved not to make movies any longer because people were losing interest in cinema. However, Covid and OTT platforms appear to have rekindled interest. I feel like making a new film”.

Recently, Adoor was seen driving himself — as always — to a cinema hall in the city to watch Ullozhukku (Undercurrent), made by the newcomer, Christo Tomy. “It’s one of the best films I have seen. Not many have used the floods more evocatively,” said the veteran, who never misses a notable film, even of debutants, and patiently queues up at film festivals.

However, his patience runs out when he sees something grossly unfair. Ullozhukku was not selected for the last International Film Festival of India in Goa or the International Film Festival of Kerala. Adoor shot a protest letter to Kerala’s culture minister. This action was similar to an incident over half a century ago. When Swayamvaram was not selected by the southern regional selection panel for national awards, Adoor despatched a cable to I.K. Gujral, then the Union information and broadcasting minister, requesting intervention. “I never got a reply. But days later, while sitting in a restaurant, I heard from a radio bulletin that Swayamvaram was chosen for four national awards! This also led to Ramesh Thapar, the jury chairman, disbanding the regional selection system altogether.” Adoor marvelled at the time when a cable from a rookie film-maker to a Union minister had such an impact. Although never a fire-spewing activist, Adoor led protest marches when the Bharatiya Janata Party government at the Centre meddled in the affairs of the Film and Television Institute of India, his alma mater. The veteran angered Kerala’s communist leaders with his Mukhamukham (1984), which portrayed the Left’s degeneration.

Even though he is happy about the commercial success of new-generation films, Adoor is not quite enamoured by them. “They are hailed more for their box office success than art. It need not stimulate uncompromising filmmakers.” It has been eight years since Adoor made Pinneyum and he is known for long intervals between films — he has made only 12 feature films in over half a century. One reason for the hiatus was his taking over as the chairman of the K.R. Narayanan National Institute of Visual Science and Arts, set up in 2016 by the state government. He brought the institute to national attention but resigned last year following internal fracas. A section of students and staff raised various charges against the institute’s director and film-maker, Shankar Mohan, including that of discrimination against Dalit students. Adoor found them baseless and backed Mohan. However, the spat led to Mohan’s resignation. Adoor stepped down in solidarity, even though the chief minister of Kerala, Pinarayi Vijayan, requested him to continue. Soon, many prominent people, including the Kannada film-maker, Girish Kasaravalli, also quit the institute's academic council. “The institute was shaping up as the best in the country. My experience has always been bitter with governments.” Adoor also recalled his resignation as chairman of the Kerala State Chalachitra Akademi two decades ago over differences with the government led by A.K. Antony.

Yet, the veteran heads the Centre for Performing Arts set up near Thiruvananthapuram by the government. This is owed to his lifelong passion for Kerala’s performing arts, such as Kathakali. Adoor’s maternal family was a great patron of the art form. Kathakali and literature were sources of solace during his unpleasant childhood in a broken family. “I remember watching Kathakali from my mother’s lap as an infant. Literature and drama enriched my boyhood. I had finished reading major works in Malayalam and many in Bengali while in school.”

Bengali cinema captivated him in FTII. “Ray inspired me most. Ritwik Ghatak was my revered teacher, and Mrinal Sen, a dear friend”. Ray considered Adoor the country’s best film-maker and many saw him as the maestro’s true successor. Adoor recalls Ray’s loud laughter while watching his humour-laden second film, Kodiyettam (The Ascent, 1977), in Delhi. Later, an ailing Ray came climbing up the stairs of the Soviet Culture Centre in Thiruvananthapuram to watch Adoor’s Elippathayam (Rat Trap, 1981). “He was my inspiration ever since I watched a 16 mm print of Pather Panchali in 1958. But our films belong to different aesthetic worlds. He was a great lyrical romantic in true Tagorean tradition. I see myself as a bit of a cynical realist,” says the veteran with a chuckle. And Ghatak? “Ritwikda was a cult figure in FTII. But as a shy person, I never tried to have any personal interaction with him. But his close disciples like Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani were my dear friends”. Adoor rubbishes the widespread gossip that Ray and Ghatak were sworn enemies. “Ghatak used to narrate Ray’s films with great admiration in classes. Ray told me cinema flew in Ghatak’s veins.”

Elippathayam was selected for screening in the Un Certain Regard category at the Cannes Festival in 1982 when Mrinal Sen served as the first Indian on the international jury in the competition category. “Mrinalda had told me at Cannes how he wished my film had competed. He always backed my films.” Elippathayam won the British Film Institute’s coveted Sutherland Trophy for the most original and imaginative film of 1982. Adoor is the only Indian to win it after Ray in 1959 for Apur Sansar.

Although a self-proclaimed cynic, Adoor insists he is no pessimist. Neither are his films, which, though dwelling on the human predicament, celebrate hope and emancipation. As I leave Darsanam, he tells me what he looks forward to at the moment — the upcoming visit of his only daughter, Aswathi, with her husband, Chhering Dorje, both IPS officers of the Maharashtra cadre, and his beloved, college-going grandson, Tashi.

M.G. Radhakrishnan, a senior journalist based in Thiruvananthapuram, has worked with various print and electronic media organisations