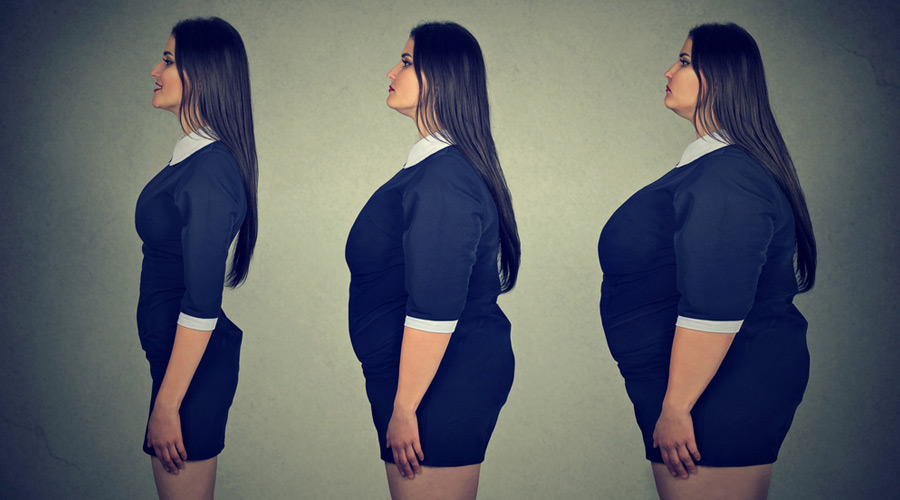

How often do we come across media portrayals that make slenderness cool? The market has its ways of strategically classifying anything that does not conform to an ‘ideal’ as undesirable. Text and imagery are used relentlessly to normalize a certain kind of ideal body-type, which is circulated as a reference for emulation. Emulation demands shaping up the body according to certain ideal standards: ideal-weight, ideal-size, ideal-shape, ideal-tone and ideal-complexion. It also requires a host of products and services to be consumed, such as training, dieting, cosmetics, drugs, medical and surgical interventions and so on.

Why is such an ideal-type problematic? What is wrong about the desire to look better? An ‘ideal’ is fundamentally elusive. No matter which ideal-type one targets, and how one designs the chase, it would lead to dissatisfaction and displeasure with one’s own body. No amount of hard work is enough to reduce that gap between the desired ideal and the achieved results because commodity and image constantly invent new problems with the body and offer new solutions through consumption.

Ideal-types are also simulated. In the era of digital manipulation, such ideal-types transform the body into a flawless form. Any representation of the body on your screen or on the hoarding is thoroughly edited. For example, Photoshop is loaded with tools like ‘liquify filter’ or ‘magic wand’ that can alter the image of the body, airbrushing aging and sagging and editing out excesses. This way, the body-image becomes even more unattainable.

Modern beauty products and their imagery fragment the body into specific parts so that each body part can then be separately attended to and exhibited. The body is thereby reduced to an obsessive-narcissist project of cosmetic artifice. It is apparent that the act of displaying is the impetus behind the cosmetic intervention: it prepares the body for the gaze. As if the body cannot be deemed beautiful or worthy of exhibition unless it meets the set standards of idealness. The body thus becomes — at once — a consuming agent and also a site for consumption.

Given the emphasis on the body through mutual gaze and self-surveillance, it also becomes a site of restraint and control. The exterior self is exposed to cosmetics, clothing and surgery, while the inner-self undergoes constant monitoring. Equally, bodies become sites of discipline and pleasure. They are perceived to be pleasurable only after they have been disciplined and shaped according to certain ideal-types. Simultaneously, the body also circulates images similar to the ideal-type: photographs of the worked-upon-body are consumed as images.

The idea of an ideal-body-type intensifies the desire to engage in comparative body-analysis between one’s own body and the distant ones that are made to appear desirable. Such a body-project only leads to perpetual dissatisfaction with one’s own shape, size, and colour as we look into the mirror or allow ourselves to be judged on measurable terms. Measuring, sizing, shaping, toning are prescribed interventions, to be tried and tested on one’s own body in order to live up to the standards of the established ideals of perfection. The tangible body and the subjective idea of beauty are simultaneously objectified and left open for endless improvements.

While normalizing the unachievable-body, the beauty industry makes us forget a basic physiological fact: that bodies come in all shapes and sizes. The definitive definition of the ideal-body that is created, sustained and marketed by the nexus of visual and popular culture machinery makes us participate in self-shaming even though we do not realize it. Feminism can only provide a politically correct moral critique of this, as we internalize the ideal-type in our everyday lives and forget that notions of femininity go beyond the inch-tapes that provide ‘objective’ readings of the body.

Sreedeep Bhattacharya is the author of Consumerist Encounters