The first time I knew myself to be in the presence of greatness was while sitting under a shamiana in New Delhi’s Modern School sometime in the last quarter of 1974. I had recently joined college and a group of friends had taken me along to hear a music concert. The performers were Ali Akbar Khan, on the sarod; Ravi Shankar, on the sitar; and Alla Rakha, on the tabla. At this distance in time, I cannot recall what ragas they played. But I do remember that I was absolutely enchanted, and that the concert was being held in memory of Allauddin Khan, who was the teacher of both Ali Akbar and Ravi Shankar.

Till that night in Delhi, my musical tastes ran mostly to Bob Dylan and the Beatles, with Mohammed Rafi and Lata Mangeshkar occasionally thrown in. Slowly, and under the instruction of two older friends — both, perhaps not coincidentally, Bengali — I began to listen more, and ever more, to our shastriya sangeet. I would bunk classes to listen to All India Radio between breakfast and lunch, the hours that the Delhi A station devoted largely to classical music. And after cricket practice and dinner, I would try and catch more music on the radio.

Nowadays, I listen to music mostly on YouTube, though I attend concerts in Bangalore when I can, and carry an iPod with hundreds of CDs on it to keep me company on long flights. The memory of that transformative night in New Delhi’s Modern School fifty years ago came back to me last week while listening to a short, but utterly magical, recording of Annapurna Devi playing Manj Khamaj on the surbahar. I had listened to that piece before; but now, somehow, it got me thinking of all that I owed not just to our musical heritage in general but to one musical gharana in particular. For Annapurna was the sister of Ali Akbar and the first wife of Ravi Shankar. She too was taught by her father, Allauddin Khan; and her chosen instrument was the surbahar. Tragically, her public career was cut short because of a bruising marriage; she henceforth became a recluse, although she continued to train students, among them the great flautist, Hariprasad Chaurasia. (Annapurna’s life and legacy are the subject of Nirmal Chander’s recent documentary film, 6-A Akash Ganga.)

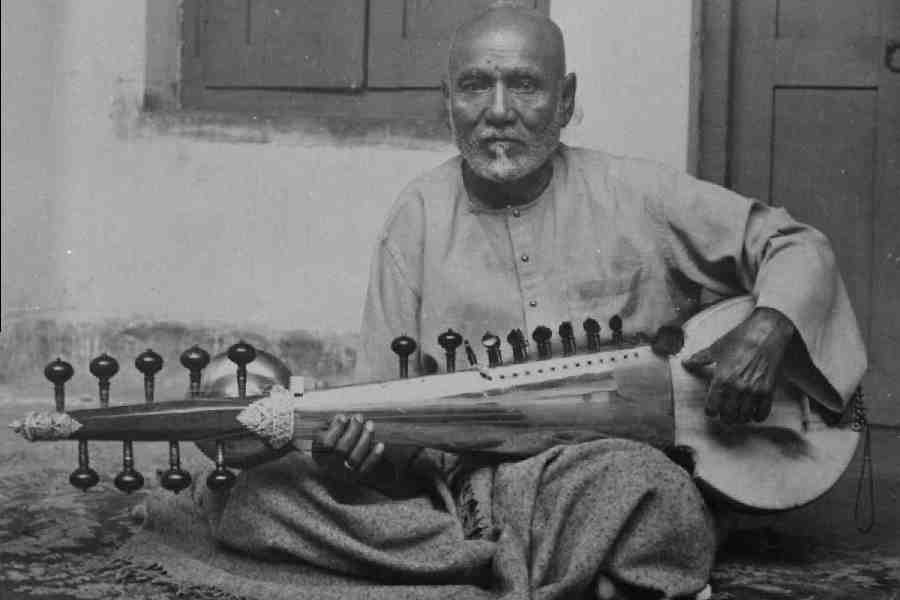

Listening to Annapurna, thinking of Ali Akbar and Ravi Shankar playing in Delhi in 1974, took me back to an essay by Ved Mehta on Allauddin Khan that I had read years ago. Mehta’s account, based on interviews with the man, is rich and colourful, although while reading it one wonders where myth and fiction end and reality and fact begin. The essay describes Allauddin’s journey from a remote village now in Bangladesh to Calcutta in search of teachers, begging and scrounging as he went along, his fortitude rewarded by instruction from stern and severe gurus. From Calcutta the ever-curious apprentice made his way to Rampur to learn from a legendary beenkar; the man refused to meet him till Allauddin threw himself in front of the carriage of the Nawab of Rampur who then persuaded the haughty Ustad to take him on.

Allauddin later made his way to the small state of Maihar, in central India, where he stayed for the rest of his life, playing and teaching music. His pupils included, apart from the trio already mentioned, such acknowledged greats as the sitarist, Nikhil Banerjee, the flautist, Pannalal Ghosh, as well as the rather less gifted Maharaja of Maihar. When not teaching, he did namaz five times a day and prayed at the town’s Hindu temple, while becoming universally known as ‘Baba’ (father in his native Bengali but also respected old sage in Hindustani).

From Mehta’s essay (which is in his 1970 book, Portrait of India), I advanced to two more recent biographical studies of Baba Allauddin Khan by Anjana Roy and Sahana Gupta, respectively. Both writers grew up as children of students of Baba; and for this reason, their books are more weighty, especially in a musical sense, than Mehta’s account. They trace Allauddin’s personal and professional journey, his mastery of many different instruments, his creation of an orchestra for Indian music and of many new jod ragas. The narration occasionally tends to the reverential; neither mentions Baba’s central pedagogical maxim, which, as related to Mehta, reads in English translation: ‘I hold with the old idea that teaching and beating go together.’ Stories I heard from my Bengali friends back in the 1970s confirm the validity of this claim. Ali Akbar and Ravi Shankar, and even on occasion the Maharaja of Maihar, were subject to their teacher’s impatience taking the form of a thrashing.

Our contemporary sensibility might find this aspect of Allauddin Khan’s character off-putting. I do, too; though I find consolation (and nourishment) in the concluding paragraphs of the foreword by his daughter, Annapurna Devi, in Sahana Gupta’s book (which may be the only thing in English she ever wrote on her father). This notes that “Baba spent over four decades of his life in Maihar — playing, teaching and sharing his divine gift of music. His disciples include an impressive line-up of some of the finest-ranking instrumentalists of the twentieth century.” Annapurna lists these bejewelled pupils: Ali Akbar, Ravi Shankar, Pannalal Ghosh, Nikhil Banerjee and so on — while leaving out herself, as much of a virtuoso at her instrument as any of the others. Then comes this very resonant last line: “Above all, Baba was perhaps the most secular individual I have known in my life.”

In similar vein, Anjana Roy writes that “Allauddin Khan was not a petty-minded ethno-centric nationalist. His patriotism blended into a broad world vision.… He never cared to see the right-hand portion of a name — the surname — which he considered to be a symbol of narrowness, as it indicated the caste or creed of the person concerned.… [H]e aspired after Hindu-Muslim unity and a healthy synthesis of all faiths and creeds.”

For five decades now I have listened, and listened some more and much more, to the music of the disciples of Allauddin Khan. However, unlike religious bigots and cricketing jingoists, music lovers tend to be ecumenical rather than parochial. There are thus great instrumentalists trained by other hands who have given me enormous pleasure too; among them are Bismillah Khan, Vilayat Khan, Abdul Halim Jaffer Khan, N. Rajam, Buddhadev Das Gupta, and Radhika Mohan Maitra. Nonetheless, it is Baba’s musical family that — when it comes to Hindustani instrumentalists — has afforded me the most collective joy over the decades. I listen often to the most celebrated of his disciples; and to others of the gharana who are superbly skilled if not so well known, such as the sarodiyas, Sharan Rani, Bahadur Khan, and Rajeev Taranath, each from a very different social and cultural background. The first two had talim from Baba himself; the third was trained by his son, Ali Akbar.

I am not a scholar of music, nor even a connoisseur of music; merely an enthusiastic amateur listener. It is in that spirit that this column is written; and it is in the same spirit that I offer in conclusion some personal favourites from the repertoire of Allauddin Khan and the musical lineage he spawned. These are Annapurna Devi’s aforementioned Manj Khamaj; Ravi Shankar‘s Pahadi Jhinjhoti; Ali Akbar Khan’s Chhayanat; Nikhil Banerjee’s one-hour-thirteen-minute-long Rageshwari; Pannalal Ghosh’s Hamsadhwani; and Bahadur Khan’s Nat Bilawal. There are also some fabulous jugalbandis of the Maihar Gharana online: Ali Akbar and Nikhil Banerjee; Ali Akbar and Ravi Shankar; even a couple of Ravi Shankar and Annapurna playing together recorded in the 1950s before the latter tragically left, or was compelled to leave, the concert stage. And I must mention one timeless jugalbandi that merges Baba and non-Baba, North and South, Hindustani and Carnatic, Muslim and Hindu. This is a Yaman/Kalyani played by Ali Akbar Khan on the sarod and Doreswamy Iyengar on the veena, with Chatur Lal on the tabla and Ramaiah M.S. on the mridangam. It was recorded some sixty years ago at the Bangalore home of Lalitha and Shivaram Ubhayaker.