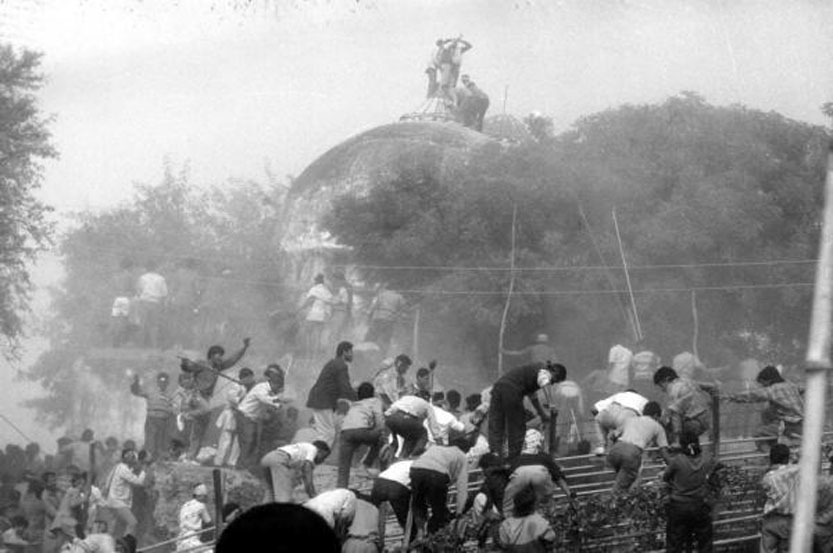

It is a rare judgment that pleases all parties. In spite of the impulse towards conciliation embedded in the Supreme Court verdict on the Ayodhya title suit, it has not erased the insecurities of some plaintiffs from the minority community. The unanimous judgment by five Supreme Court judges, including the Chief Justice of India, awards them five acres of land for a mosque, but they are worried that this land may be far from the original spot. The district has been renamed Ayodhya, so the government might even offer them space in Faizabad, since sangh parivar activists do not want a mosque in Ayodhya town. Their fears must be understood in the context of the judgment. Its carefully wrought balance is much valued because the land dispute was not over farming but religion — space for worship — for which justice was sought within the secular framework. But the background of the title suit cannot be wished away. Politics garbed in religion destroyed the Babri Masjid in 1992, an act the court condemned. It is a paradox of the Indian justice system that the case against the perpetrators of that destruction is still hanging fire, while possession of the land in the name of a mythological figure supposed to have been born at the exact spot where the mosque stood has been decided in court.

Not faith but evidence — of continued worship on the land — should decide the issue, felt the court. It found this evidence to be in favour of the Ram worshippers; representations from the minority community also made claims of prayers there since 1856-57. The references in the judgment to ancient texts, travelogues and other documents, and to the archaeological find of a structure below the demolished mosque, not necessarily Hindu — the excavation was ordered by the Allahabad High Court — seem puzzling: can a land title be decided by centuries-old history? What precisely is the difference, then, between faith and evidence if both rely, to a greater or lesser extent, on belief? But what is not belief and not ancient is the planned demolition of the mosque in 1992. Yet the court found the evidence strong enough to award the entire plot to a future temple — while condemning the mosque’s demolition.

In effect, therefore, the powers behind the demolition have got what they wanted. While there is hope that the two communities will now move forward in peace, that ‘peace’ may have come at the cost of a shift towards the majority community, a fundamental change in India’s polity. As long as the battle for majoritarian triumph was political, there was hope for India’s democratic secular identity; the Ayodhya verdict, maybe to prevent conflict, has changed that. No wonder L.K. Advani, an accused in the Babri Masjid demolition, feels smugly vindicated. The senior leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party has the Bajrang Dal and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad in triumphant company.