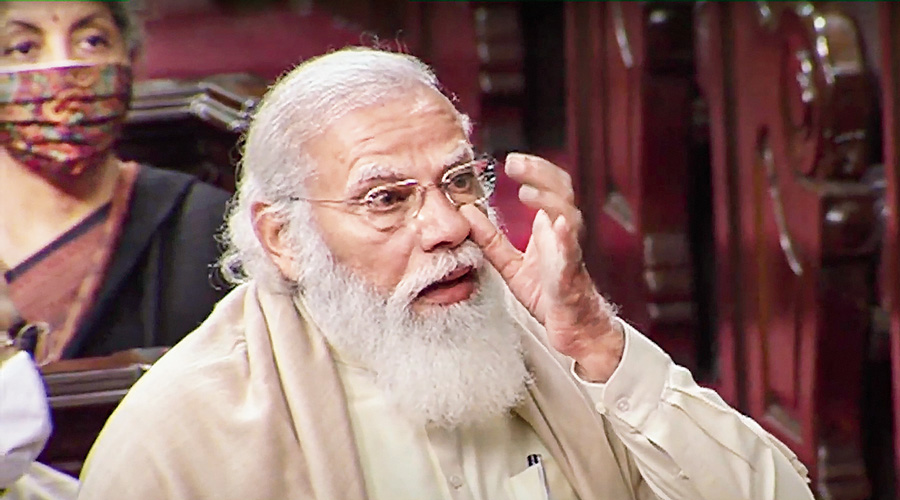

In a nation where judges believe in the existence of tearful peacocks, a land that has had a fair share of the proverbial crocodiles in public life armed with leaking tear ducts, why should the prime minister not have the right to shed a tear or two? Moved by the imminent departure of a member of the Congress from the upper House, Narendra Modi’s eyes were reported to have welled up, setting tongues wagging. The chatter, however, is not unwarranted. Mr Modi has repeatedly endorsed India to rid itself of the Congress; yet, the Rajya Sabha’s mukti from a Congressman caused him to turn uncharacteristically sentimental. Then there is the bit about Mr Modi’s ability to choke up — but only during his hour of triumph or while recounting sacrifices. India had seen Mr Modi’s tears when the former lauh purush, L.K. Advani, attributed the Bharatiya Janata Party’s electoral triumph in 2014 to the prime minister; his eyes had turned misty, again, while being described as a divine entity.

However, a scrutiny of the global history of the politics of tears would provide a more likely explanation of all the excitement. Iron men — Mr Modi and his admirers believe that he is of the ilk — are not known for having misty eyes. In fact, tears can extract a political cost: Britain’s ‘Iron Lady’, Margaret Thatcher, was once roasted for admitting that a bad day at the office would make her cry at home. Conversely, Angela Merkel has been glorified for her stoicity. This denouncement of a perfectly natural response is linked to popular culture’s fallacy of perceiving emotion — the element that separates Man from Beast — as a sign of weakness, a testament to the loss of control over the self, a challenge to android masculinity. Yet, politics remains flooded with Weepy Iron Men. Oliver Cromwell — he had asked for the King’s head — was known for his watery eyes; Winston Churchill was successful in keeping the dreaded Nazis at bay but not his tears; Vladimir Putin has been caught sniffling; Barack Obama was quite a cry-baby.

Politicians’ willingness to turn into pulp in public must be read as proof of their ability to understand the shift in society’s relationship with tears. In this Age of Technology, where efficiency is prioritized over emotions, the ability to forge a solidarity with the people is increasingly being determined by sentimentality and compassion. A smile, a tear, a hug have thus been transformed into acts invested with political capital. But there is also a related ethical question. Sentimentality can have a desirable effect when it is accompanied by sincerity. In its absence, a politician wearing his/her heart on the sleeve could be criticized for being a performer, the possessor of — much like Cromwell — a ‘supple conscience’. It is for India to decide whether its prime minister has a conscience of a different constitution. A man unmoved by the deaths of protesting farmers is also the man who weeps on other, sundry matters.