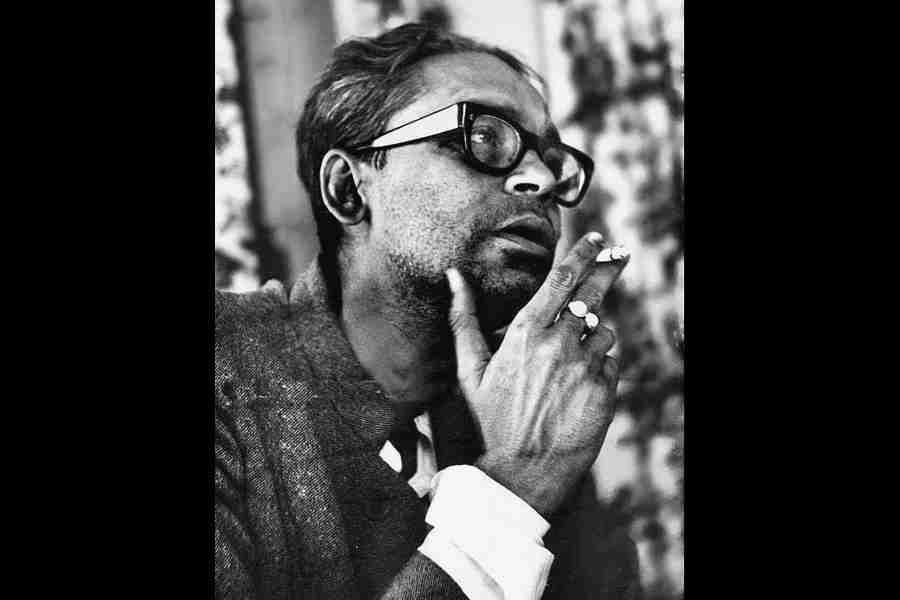

Indian filmmakers could have done a lot to awaken society’s sleeping conscience to the tribal experience. Ritwik Ghatak, who turns 100 this year, was an exception. He made many worthwhile attempts to understand the Adivasis of Bihar and Bengal, in particular. Although he was not trained in anthropology or psychology, Ghatak has helped us understand varied facets of the Adivasi presence — their collective psyche, their rootedness in nature, or their sense of abandon to cover up their material deprivation, which has often led to an ineffable spiritual desolation. The extended dance-and-drink sequence in Ajantrik, for instance, is not just mesmerising cinema but an authentic record of fun and games, albeit laced with sadness, that these primitive people can engage themselves in almost as compensation for the other things of life that they have been robbed of by guns and governments.

It is a pity that Ghatak failed to complete his documentary on the legendary tribal painter-sculptor of Santiniketan, Ramkinkar Baij. Had he completed it, the film would have not only upheld the figure of the homegrown artist as a creative rebel carrying universal meanings, but also allowed audiences a grand view of a people rich in gifts of the spirit inconceivable to modern, technological man.

Ghatak was temperamentally suited to understanding and appreciating the tribal persona. Middle-class, bhadralok, city-bred, Tagore-lover, cultured and enlightened in a modern, 20th-century way, he was, however, both inventive and iconoclastic enough to declass himself emotionally without letting go of his enormous intellectual baggage. In the process, he ran into contradictions, but he never allowed these to prevent him from discovering in the Adivasis a many-splendoured subject worthy of stark, at times subtle, but never seductive depiction. It was this soil sensibility in him that attracted Ghatak to the earthy genius of Ramkinkar, not to the sophisticated genius of Benode Behari Mukhopadhyay immortalised by Satyajit Ray in the documentary, The Inner Eye.

In Jukti Takko Aar Gappo, Ghatak devoted considerable space to the rich folk art and marginal existence of the Chhau maker, Panchanan Ustad, whose striking robustness, child-like innocence and great humanity remind the viewer of Ramkinkar. Panchanan Ustad’s personal lifestyle and his grassroots perceptions of life, art and society are established with the help of cinematic strokes at once bold and bewildering.

The detailed Chhau sequence in the film, where the camera is as energetic a performer as the masked men and children playing familiar characters out of the epics, stands out in this largely autobiographical road movie. The film, characterised by narcissistic excesses, may seem overwrought in parts, but what is more relevant here is that the masked dance, complete with maces and spears, pipes and drums, exaggerated movements, stylised poses, and audience participation, amounts to an in-depth probing of the experiences of an unjustly deprived people who are, paradoxically, rich enough to keep their life flow and artistic traditions alive.

Many of Ghatak’s short stories, which are being discovered and assessed anew, are also set in tribal territory. Towards the end of his short life during which he worked at a feverish pace, tribals came to occupy an increasingly important place in his art. True respect combined with an inexhaustible eagerness to know them in an intimate way may have been one of the hallmarks of this great artist’s small but scintillating oeuvre.

Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema, society and politics