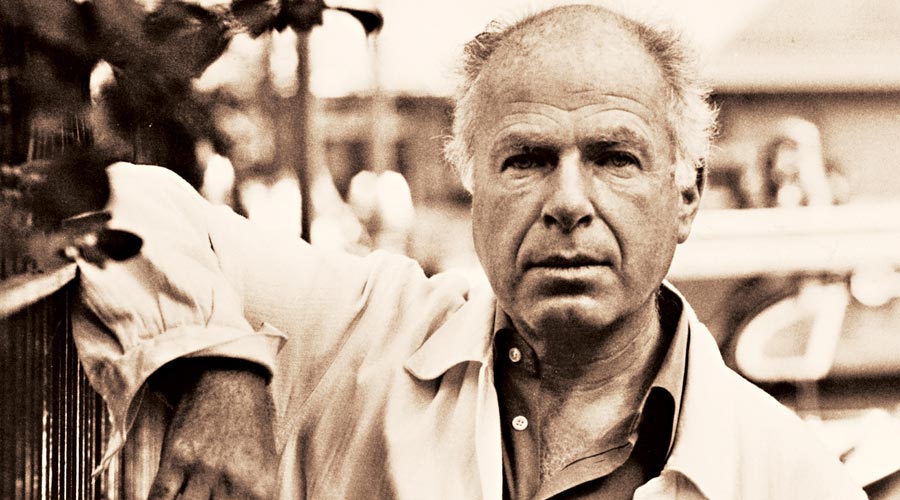

With the passing of Peter Brook, we say goodbye and ‘Bravo!’ to one ofthe great pioneers and philosophers of modern theatre. Brook lived a long and full life, leaving us at the age of 97, apparentlywhile still working on his next project. As with other figures in the arts who have both transformed their fields radicallyand had a long innings to work on the revolutions they’ve brought about, it’s startling to see where Brook began and where he finished.

Born in England in 1925, Brook came of age during the Second World War but ill health stopped him from joining the army. Such was the young man’s brilliance, however, that by the time he was 20 he was already assisting on Shakespeare productions at Stratford. By the time he was 24, working in London, he was fired for conceiving and directing a too risqué production designed by Salvador Dalí. Within the next fifteen years, Brook had totally shaken up the way Shakespeare was performed in Britain and delivered legendary stagings of powerful contemporary plays. Far too often, we see the graph of young brilliance beginning to dip by the time an artist reaches his or her mid-forties— talents plateau; the ideas become less fecund; the offerings begin to feel somewhat repetitive. In Brook’s case, the opposite happened — abandoning his comfortable perch at the commanding heights of British theatre (plus some success across the Atlantic), he moved to Paris to set up his own repertory and performance space in a dilapidated old building near the Gare du Nord. Brook had realised that the opportunities and funding for real experimentation would be far more limited in a straight-laced England whereas the French were much more open to funding projects and experiments that risked failure.

This was a moment of great churning in European theatre and Brook was not alone in embarking into unknown territory, trying to leave behind the safety of the proscenium and fixed text. In Poland, Jerzy Grotowski had long begun his own experimentation, as had Eugenio Barbain Denmark; in Germany, entering the mix from the direction of dance, Pina Bausch started her work in Wuppertal. Tadashi Suzuki was working with overlapping concepts in Japan, as were several American groups. Here in India, Badal Sircar began to work with his Third Theatre, which did away with the need for a theatre and stage, and Ratan Thiyam and a number of others also began to work with similar concepts.

Brook’s lifelong search was about different ways to arrive at performance experiences that were freshly powerful and genuinely transformative for both actor and audience. In his great text from 1968, The Empty Space, Brook talks about what he terms “the DeadlyTheatre”: “If we talk of deadly, let us note that the difference between life and death, so crystal clear in man, is somewhat veiled in other fields. A doctor can tell at once between the trace of life and the useless bag of bones that life has left; but we are less practised in observing how an idea, an attitude or a form can pass from the lively to the moribund. It is difficult to define but a child can smell it out.” Acutely, Brook points out that cleaving to a form for form’s sake was never the answer,“... it is not just the trivial comedy and the bad musical that fail to give us our money’s worth — the Deadly Theatre finds its deadly way into grand opera and tragedy, into the plays of Moliere and the plays of Brecht... In a living theatre, we would each day approach the rehearsal putting yesterday’s discoveries to the test, ready to believe that the true play has once again escaped us. But the Deadly Theatre approaches the classics from the view point that somewhere, someone has found out and defined how the play should be done.”

From the early 1970s, Brook moved his group not only out of conventional theatres but also often out of Europe and out of cities to perform in rural Africa and Iran. Having re-worked the classics of the Western canon, in the early 1980sBrook began his largest and most complicated project, The Mahabharata. The resulting production received much acclaim, with one critic recently saying that he felt like he was “walking on air” after having seen all nine hours of it. There was also criticism, with sharp and valid questions raised about whether this was yet another appropriation of our myths and history à la Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi, a cultural heist of our indigenous narrative artefacts and performative traditions, decontextualising and exoticising them for the consumption of a largely Western audience.

While I would argue that Brook’sproject, both the specific Indian epic and the larger project, was far more complex and honest and, in fact, in another galaxy from the Gandhi film, I would also emphatically agree that this questioning isn’t (and shouldn’t be) going away anytime soon. But even as we deploy (perhaps a Brooksian) forensic examination to dismantle and interrogate Brook and his work, we need to be grateful to the man for many things.

Having ransacked the texts of the Greeks, of Shakespeare, Molièreand other Western playwrights, Brook arrived at realisations that forced him to question the subservience of Western theatre to the written word, inspired him to exile the text from the performance, and forced the words to fight their way back each time to take a more equal position with the unspoken. Even with physical movement, Brook is the one who brilliantly articulates that “... all the different elements of staging —the shorthands of behaviour that stand for certain emotions; gestures, gesticulations and tones of voice — are all fluctuating on an invisible stock exchange all the time.” Time and time again in his process, Brook insists on the excruciatingly difficult, honest distillation of intention and instinct, something which is worth emulating. And yet, after all is said and done, in the constant struggle against the Deadly in art, Brook’s motto might be the axiom laid down by the Situationists: Boredom is counter-revolutionary. Brook also refers to Antonin Artaud, the French theatre visionary — “He wanted the theatre to contain all that normally is reserved for crime and war.” In these times when we are inundated in hollow repetitions of all sorts, when from behind the simulacri put up by the powerful we are constantly ambushed by conflict and violence, these are crucial lessons for all artists to keep close at hand.