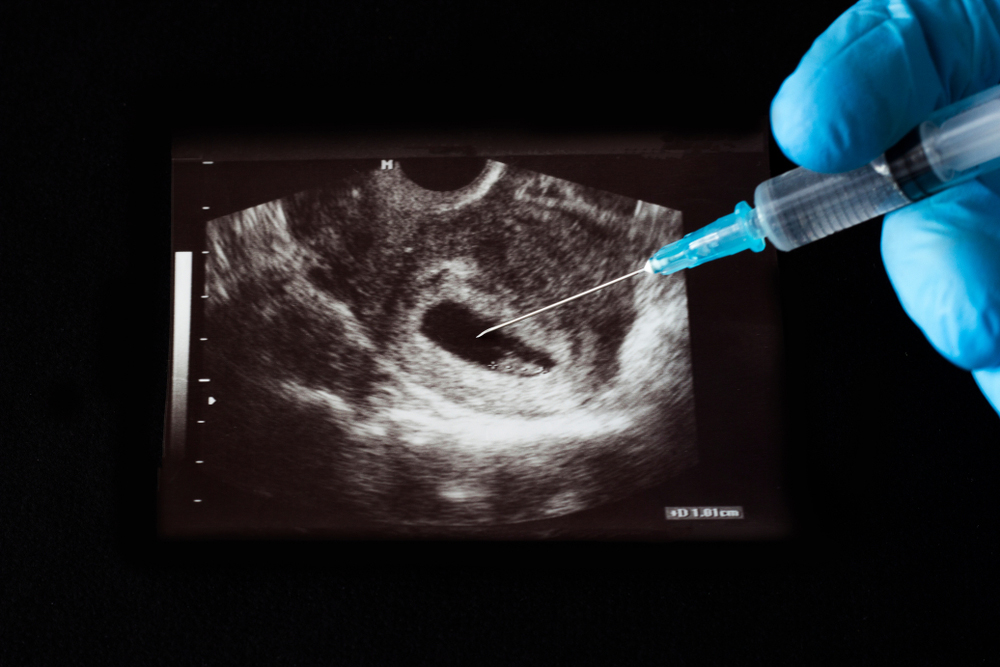

In conservative societies like India, where women struggle for basic rights, changes in policy geared towards their uplift are greatly welcome. Such a change occurred recently when the Union cabinet cleared a long-overdue amendment to the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971 to raise the legally permissible limit for an abortion to 24 weeks from 20 weeks. The amendment also accepts failure of contraception as a valid reason for abortion for both unmarried and married women, ensures confidentiality — this is crucial in a nation where abortion is shrouded in religious and cultural stigma, even if it is life-saving — and scraps the upper limit in cases where substantial foetal abnormalities are diagnosed.

While it must be asked why these changes took so long to be approved, their importance cannot be overstated. The extension to 24 weeks is designed to benefit survivors of rape and incest, minors and differently-abled women, for whom ignorance, a culture of silence, lack of support and the fear of ostracization all contribute to the inability to either recognize a pregnancy before 20 weeks or to seek a timely, safe and confidential abortion. Many women who find out too late that they are pregnant are forced to move court to get an abortion. Given that biology and India’s justice delivery system greatly differ in pace, numerous women find themselves at the mercy of back-alley abortion providers, resulting in a massive risk to their reproductive health and even their lives. Thus, while India’s abortion law has been more progressive than those in other nations — abortion was banned in Northern Ireland till last year, and in most parts of Europe, it is allowed without restriction only up to 10-14 weeks’ gestation — poor socioeconomic conditions have affected its implementation. Ignorance around modern contraception has had disastrous consequences: a 2018 study showed that 50 per cent of the pregnancies in six large Indian states were unintended. Thus, the availability of safe, affordable termination services is crucial. However, even the amendments are not without conditions: two physicians need to approve abortions in the 20-24 week window, thus putting the procedure out of reach for many women from marginalized communities who may have no access to doctors. Does the expansion of the law then truly grant women the autonomy they need? And will it have its intended effect unless sex education becomes part of regular curricula — especially in rural areas where segregation between the sexes is still the norm — and women are made aware of their legal reproductive rights?