Less than a quarter of the way into the Congress’s now neutered negotiations with Prashant Kishor on defining a course out of the bottomless bogs, Rahul Gandhi, the former and who-knows-somedaymight-be president of the party, set out on his summer’s outing to Europe. This is not about Kishor and what he could or could not do to reverse the Congress’s fortunes. Having once suffered a sour experience with the ruling house of the Congress (and probably aware that not much had changed in its manner), the risk was Kishor’s to take or walk away from. It is the party’s will to invest in a comeback opportunity that has, once again, been revealed as a forsaken thing.

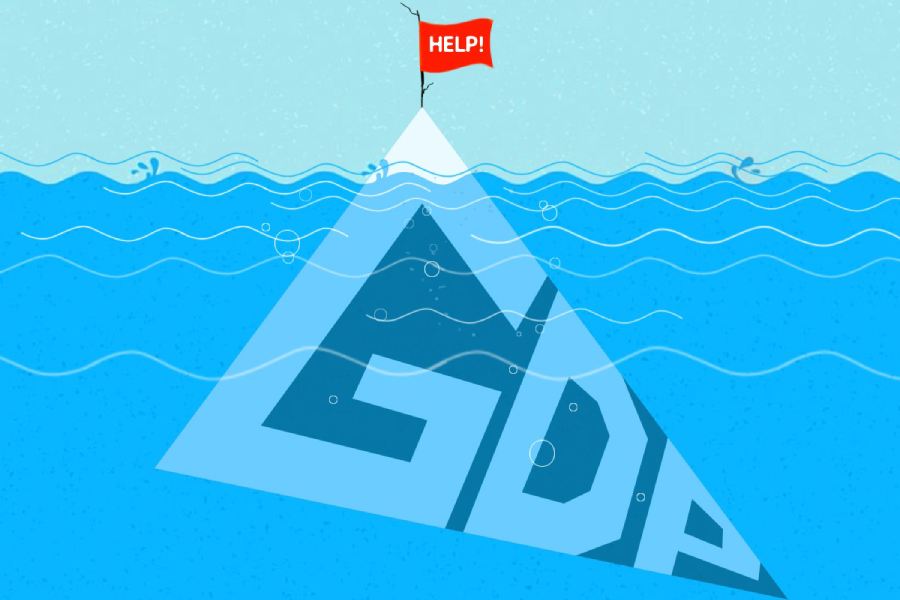

Since it lost power in 2014, the Congress has slalomed in an astonishing fashion. If there could be an aspect of the Congress more astonishing, it is that it doesn’t appear bothered with, or even sensed of, the depths of its plunge. The few signs of recovery it revealed, it frittered — the victories in Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan have either become things of the past or are well on their way there. Kamal Nath, for all his fabled backroom heft, could not prevent his swift sundering by the Bharatiya Janata Party. Amarinder Singh was toppled by his own and replaced by factional rivals so taken by their ambitions and so riven that they were never going to measure up. Sachin Pilot is an asset allowed to turn ruefully sore in Rajasthan. T.S. Singh Deo of Chhattisgarh is similarly aggrieved. It isn’t hard, or fanciful, to foresee the Congress smoked wholly out of power; it shan’t be unfair then to argue that the Congress contributed most to the establishment of a Congress-mukt Bharat.

How summarily the party of Indian nationalism and, for the most part, governance has lost the institutional memory of power and ways of invoking and working it is a story waiting to be told. If only someone were allowed to access and decode the murmurs that hang in the closed-door air of 10 Janpath. Or, perhaps, it is not at all an arcane thing; it is such a plain thing, it deceives notice. That plain thing is the delusion of disappeared grandeur and the refusal to recognize it for what it is.

Rahul Gandhi continues to inhabit a convenient schizophrenia — he becomes just an MP from Wayanad, nothing more, when it comes to responsibility, party potentate for the rest. He is, for all purposes, the leader of the party, its chief spokesman and campaigner, and its chief arbiter. If the critical issue of the formal leadership — to be decided at an election whose dates remain undecided but cannot be forever put off — lies unresolved, it is also because Rahul Gandhi has chosen not to resolve it. He will not categorically say he is prepared to lead the party, he will not categorically say he will not.

Little moves in the Congress without Rahul’s bidding but he deigns to do so little that the party appears paralysed in postural discomfiture. It cannot be said for sure, for instance, whether a ginger group — in this case the G-23 — was allowed to taunt and fester for such a length of time within the party. The de facto leader sits across a formidable cast of adversaries within his tent and isn’t able — or willing — to do anything about it.

Rahul also appears unbothered by the what next. A reading of his lengthy resignation letter following the debacle of 2019 makes that plain. It is, in fact, a theoretical, even ascetic, rejection of power and electoral politics. “My fight has never been a simple battle for political power,” he wrote, “[w]e didn’t fight a political party in the 2019 election. Rather we fought the entire machinery of the Indian state, every institution of which was marshalled against the [O]pposition… Our democracy has been fundamentally weakened. There is a real danger that from now on, elections will go from being a determinant of India’s future to a mere ritual.”

He inhabits, and seldom omits to articulate, the central ideas of the Constitution and the politics of compassion, plurality and inclusion which he believes are gravely imperilled. His resignation missive, in fact, presaged some of the darkness that has now come into open play. “The attack on our country and our cherished Constitution that is taking place is designed to destroy the fabric of our nation,” he wrote with cold clarity, “The stated objectives of the RSS, the capture of our country’s institutional structure, is now complete… The capture of power will result in unimaginable levels of violence and pain for India. Farmers, unemployed youngsters, women, tribals, Dalits and minorities are going to suffer the most. The impact on our economy and nation’s reputation will be devastating…” He spoke too in that letter of his ‘commitment’ to fight the challenge as a “soldier”. But does his demeanour reflect those intentions? Has he been able to invent strategies — or display commitments — that will invoke that battle? Is he willing to give his worldview the legs and the energy to compete in the race, much less win it? Is the objective of power even in his crosshairs? He has kept his party effectively confounded on much of that.

The Congress and Rahul Gandhi are, of course, entitled to run their affairs as they wish to and, on the evidence of an inexcusable length of wasted time, run the enterprise aground. What they are not nearly as entitled to as the nation’s oldest political enterprise is to offer neither harbour nor hope to the majority of votaries who still do not subscribe to Narendra Modi’s model of the destruction of the idea of India. That’s the heinous dereliction the court that rules the Congress is really guilty of.

sankarshan.thakur@abp.in