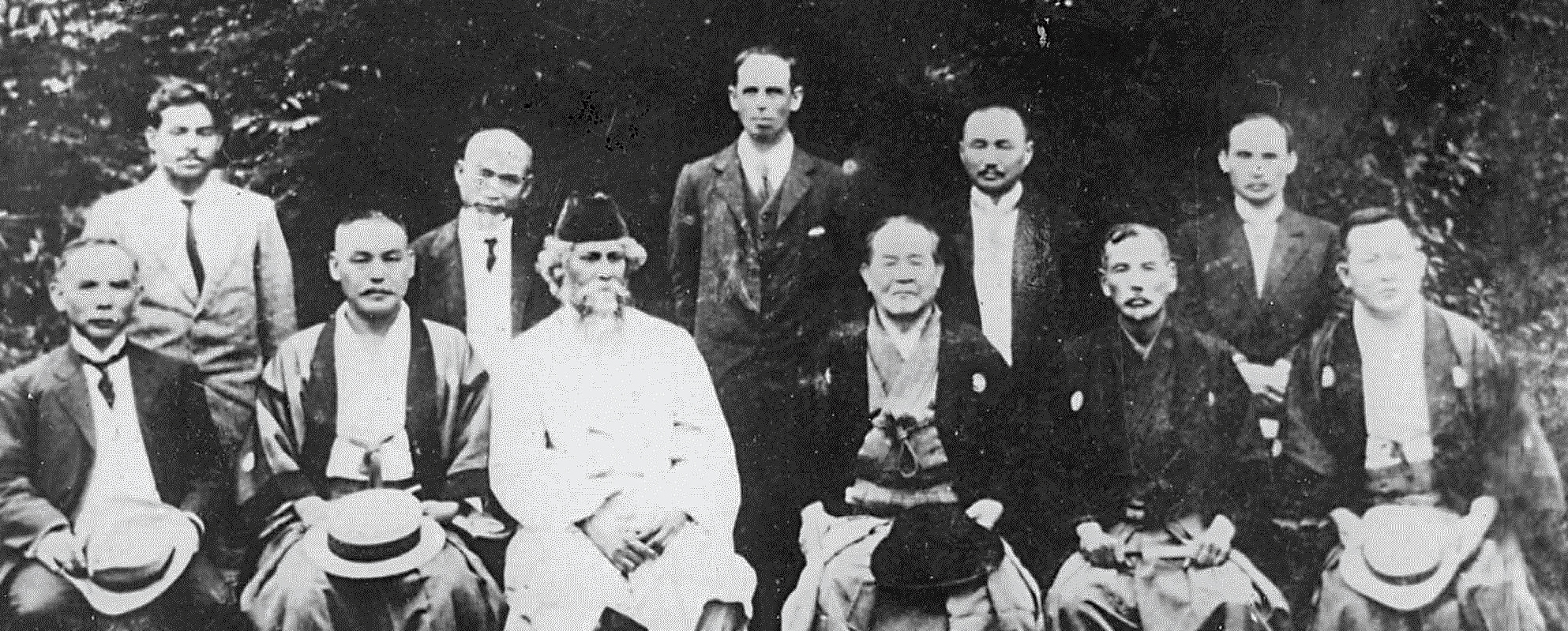

A little over a century ago, a man who had been born in a British colony, and who would die in it, pronounced this judgement, “The idea of the Nation is one of the most powerful anæsthetics that man has invented. Under the influence of its fumes the whole people can carry out its systematic programme of the most virulent self-seeking without being in the least aware of its moral perversion, — in fact feeling dangerously resentful if it is pointed out.” He made this statement in the United States of America right in the middle of what would later be labelled the First World War. The man was, of course, Rabindranath Tagore, and this is one of several prescient pronouncements he made as he toured Japan (picture) and the US in 1916, comprehensively critiquing the canker of nationalism even as the world seemed intent on destroying itself at the altar of jingoistic patriotism.

His three lectures, “Nationalism in the West”, “Nationalism in Japan”, and “Nationalism in India”— in that order — along with the English rendering of his Bengali poem, “Shatabdir shurjya aaji...” titled “The Sunset of the Century”, which were collected and published as the book, Nationalism, by Macmillan, New York, in 1917, earned Rabindranath an enormous amount of criticism bordering on outright hostility, not only from the press and the people of the two countries where he had delivered his talks but also from a section of the Indian intelligentsia, which interpreted his denunciation of nationalism as an act of betrayal.

As Rabindranath’s biographer, Krishna Kripalani, noted, somewhat ruefully, “His lectures on Nationalism were also ill-timed. Though he was right, prophetically right, in what he said and must be admired for his courage in courting abuse, the time was inauspicious. Europe was in the throes of a great calamity and thousands of young men were dying on its battlefields... the tide of sympathy for Britain was rising fast in the United States and very soon American lives would be sacrificed. It was hardly the time to condemn what seemed holy and heroic as a vast delusion caused by ‘Evil incarnate’. What would today find an echo in the minds of millions of men and women all over the world who have known the horrors of two world wars was then a voice in the wilderness.”

In the opening essay of Nationalism, Rabindranath had posed the question, “What is this Nation?” and answered it by asserting that a nation “is that aspect which a whole population assumes when organized for a mechanical purpose”, and in “Nationalism in Japan”, he had cautioned the people of that country against accepting the (negative and enervating) values of Western nationalism, which he likened to “some prolific weed... based upon exclusiveness” which was “overrunning the whole world”.

Rabindranath’s words kept echoing as I watched the Lok Sabha election results come in live on television on May 23 and took on even greater urgency as I heard the president of the Bharatiya Janata Party and our now and future prime minister address their party’s workers in triumphalist nationalist terms later that night. In poignant, despairing counterpoint was the torrential outpouring of rage, revulsion, helplessness, and despair that flooded my WhatsApp groups. How could this happen? Have we as a nation gone mad? If 30 per cent of its voting population is Muslim and the BJP has received over 40 per cent of the vote in West Bengal, are we to believe that a significant number of Muslims have voted for a party of Muslim-intolerant Hindu nationalists? How could they? And so on and so forth.

Over the next couple of days, as the reality of the election results sunk in, I noticed subtle shifts in stance among neighbours, colleagues, and acquaintances. Some started to find positive virtue in the prime minister’s ‘statesmanlike’ victory speech, especially in the bits where he had promised to be faithful to the Constitution, follow the principles of federalism, dedicate himself soul and body to Bharat Mata, and so on and so forth. Others spoke of the TWINA (there was/is no alternative) factor, people’s disenchantment with the ruling party in West Bengal, the rays of hope emanating from Kerala and Punjab, and suchlike. A few began to speak openly of how ‘minority appeasement’ would now end ‘once and for all’, and how the need of the hour was for a strong, decisive leader to guide India to take strong, decisive strides on the global stage and so on.

As days become weeks, then months, then years, I have no doubt we will make our peace with our ruling dispensation — perhaps willingly, perhaps with (seeming) reluctance, perhaps in combative mode. Some will undoubtedly abandon principle, and party, to jump on new gravy trains, making ‘minor’ adjustments to food habits and personal proclivities to better fit in and work for the benefit of an independent, strong, powerful India. Which is where my thoughts turn, yet again, to that philosopher-poet-prophet who had also written, “Even though from childhood I had been taught that the idolatry of Nation is almost better than reverence for God or humanity, I believe I have outgrown that teaching and it is my conviction that my countrymen will gain truly their India by fighting against that education which teaches them that a country is greater than the ideals of humanity.”

Eight years after he had earned opprobrium for his views on nationalism, Rabindranath would return to Japan to say, “I have come to warn you in Japan — the country where I wrote my first lectures against Nationalism at a time when people laughed my ideas to scorn. They thought I did not know the meaning of the word, and accused me of having confused the word Nation with State. But I stuck to my conviction and now after the war do you not hear everywhere the denunciation of this spirit of the Nation, this collective egoism of the people, which is universally hardening their hearts?”

And though he retained his deep distrust of the nation until the end of his life, Rabindranath never lost his faith in humanity. In his last public address, made a few weeks before his death, and in the midst of another World War, he discerned “the crumbling ruins of a proud civilization strewn like a vast heap of futility”, and yet declared that he would “not commit the grievous sin of losing faith in human beings”. Words worth pondering in confused and troubling times.

The author is professor of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, and has been working as a volunteer for a rural development NGO for the last 30 years