Fiscal and monetary policies announced this month are devoted to recovering growth and putting it on a sustainable footing. In this year’s budget presented on February 1, the government unveiled its post-Covid macroeconomic strategy. It chose capital investment to anchor medium-term growth, avoiding relief measures or a safety net cover for millions rendered jobless by the pandemic. While the logic of the former’s larger multiplier effects upon private investment, employment and incomes is indisputable, the risk is that the economically vulnerable sections could suffer permanent setbacks from prolonged economic duress. An alternative spending mix, splitting a portion of capital expenditure for front-loaded deployment towards temporary consumption enhancement, would have hit harder at the downturn and helped avert such a possibility.

There is a large macroeconomic gap to cover in the wake of Covid-19. National output is estimated at having shrunk as much as -7.7 per cent in 2020-21 by the Central Statistics Office. In 2021-22, the government projects real gross domestic product to rebound 10 per cent from this depth; adding the rate of inflation, growth will be 14.4 per cent. This looks very robust but is actually technical because of the deep plunge. It therefore reveals little about the strength of the recovery. For better understanding, most compare this to the pre-Covid output, setting the 2019-20 level to 100; in 2020-21, the fall is to 92.3, from where it will lift to 102.3 next year. So the economy will have grown 2.3 per cent over two years. For the individual Indian earner, this means a reduction in annual real income to Rs 99,193 in FY21 from Rs 1,08,645 in 2019-20, a monthly loss of Rs 788 in the Covid-19 year. Next year too, her annual earnings will not be fully restored, remaining to be recouped in 2022-23.

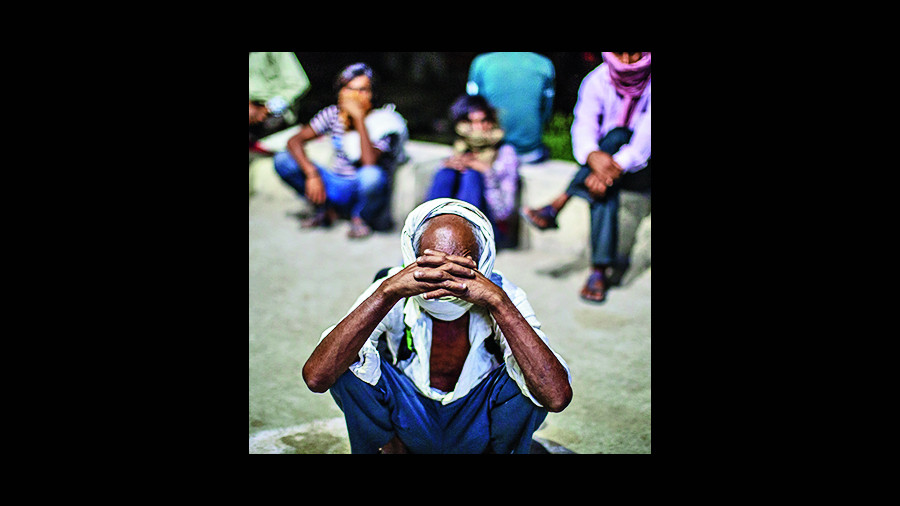

Relative to this recovery, the scale of economic loss is staggering. The per capita income representation above is not equally distributed across the population. The non-linear impact of Covid-19 has hit some segments much harder, such as hospitality, travel and retail, amongst others. This has been unfolding in the form of an uneven or what is called a K-shaped recovery: the winners gain big as observed from the unspent incomes and profits, while the bottom-earners and weaker firms fall even lower. The associated employment losses have been huge, with continued losses of jobs and incomes as businesses either shut shop or cling on in leaner form and regain strength through savage cost-cutting.

The precedents were none too strong either. For a full grasp of the stress in the labour market, the pre-Covid overhang of the growth slowdown needs reckoning as well. The rapid descent of growth to 4 per cent a year ago — half of that recorded in 2016-17 and an alarming 2.5 percentage point fall in just one year — had earlier taken a toll upon consumption and employment. For example, the 2017-18 consumption expenditure survey, officially unaccepted but some findings of which were reported, had shown national unemployment at its highest, 6.1 per cent, in four decades, with a 3.7 per cent fall in monthly per capita consumption (mainly food) over the levels in 2011-12.

There is insufficient timely alleviation in the budget to help tide over at least the duration of the economic reopening that can be expected to restore some of the temporary job and income losses. While the budgeted capital investments and other measures to incentivize domestic production and exports will take time to affect aggregate demand, a period of prolonged economic pressure could mean that second-round income effects take hold, resulting in a permanent slipping back of the vulnerable segments. It is difficult for some deeply wounded parts of the workforce to bounce back independently without policy support. It is likelier that enduring shocks to consumption and incomes will tip the peripheral earners and those at the margin into poverty besides the ones who may already have done so before.

Late last year, the World Bank estimated that Covid-19 probably increased the number of extreme poor by 88 million, reversing the steady decline in global poverty since the nineties that lowered the number from 1.9 billion to 689 million. India contributed majorly to this decline — before the revision of the international poverty line in 2015 (from $1.25 to $1.90 per day), the number of extreme poor in India fell by 8.1 per cent, from 300 million to 99 million by 2010, in five years’ time. Using the intuition that growth is the most robust driver of poverty, Homi Kharas of Brookings, a think-tank based in the United States of America, combined poverty data with the International Monetary Fund’s growth forecast in October 2020 (then -11 per cent for India) to measure the pandemic’s impact; these estimated that about 120 million people worldwide would be extreme poor in 2020 relative to 2019, with the biggest impact likely upon India. Now, the expected contraction is less, -7.7 per cent, but the risk of reversion or slippage into poverty remains substantial unless countered by quick and strong growth.

This illustrates the scale of the post-Covid challenge. The government’s main plank to grow out of the pandemic is a multi-year spending push to infrastructure. The shift to capital investment over other forms of spending is because the former is job-rich; indeed, construction work engages a higher number of unskilled and semi-skilled labourers over other forms of labour. However, infrastructure expenditures take long to kick off, a couple of quarters at least, with lagged impact upon aggregate demand. In the meantime, a slower period of demand growth minus temporary relief could accentuate or convert what might be temporary income-employment effects into lasting ones, and an increased prevalence of poverty. If consumer demand remains subdued, falls back after an initial spurt from pent-up pressures, firms or sellers may find it difficult to sustain profits or strength, slowing down investments and overall recovery.

Many point to complementary structural innovations, such as labour and agriculture markets, privatization, bad bank, and so on, that further augment medium-term growth prospects. These too are in the distance. The growth trajectory visualized ahead is not unduly strong. From the 10 per cent peak in 2021-22, the economy is expected to grow in the 5-6 per cent region until 2025-26, according to the post-budget explanations by senior government officials. This appears insufficient or not a tide that is robust enough to lift all boats.

Under the circumstances, even with the resource constraints that the government is operating with, an upfront provision of short-term income support from a part of budgeted capital expenditure to uphold aggregate demand with infrastructure expenditures taking up the baton thereafter may have been a superior strategy. A more forceful punch would minimize the risk of a feeble, prolonged recovery and of the transitory losses turning into permanent ones. Just as strong, robust growth lifts all boats, a slower recovery does the converse.

The author is a macroeconomist