When he arrived in England in the early 1970s to begin a life of self-imposed exile from an India that never really understood or appreciated his quirky erudition, Nirad C. Chaudhuri is said to have remarked that it was like returning from the battlefront.

Niradbabu was an incorrigible contrarian who often said things calculated to shock and, in the process, give himself a laugh. However, the idea of the erstwhile mother country being a refuge from crassness — if you knew how to avoid its seamier underside — has always held out an appeal to those who felt somewhat detached from the jostle of life. Yet, the Anglophilia of the Unknown Indian was never blind. Even while living in an agreeable part of gentle Oxford, Niradbabu couldn’t but lament — in the words of the famous hymn — the “change and decay, all around I see...” Writing in The Daily Telegraph in 1988, he observed: “In England today, the public aspects of decline are tacitly admitted… There is a startling acceptance of brutishness and incivility. But there does not seem to be even a suspicion that decay may also have penetrated the English mind, although no external decadence can come about without inner decadence having set in.”

Some 33 years after that article was published, the outward signs of decline are less evident. The London I first encountered in 1975 needed a strong dose of urban renewal. Today’s London is energized, smart and very, very prosperous. The Brexit scare notwithstanding, the United Kingdom has returned to being an agreeable place attracting everyone, from Russian oligarchs to illegal immigrants from North Africa, and retaining its role as a global financial centre. It even boasts a prime minister who, for all his other imperfections, has a way with words and an impish sense of humour.

Moreover, as I discovered during visits last month to Rudyard Kipling’s home in Bateman’s and Winston Churchill’s country retreat in Chartwell, both lovingly cared for by the National Trust, the “green and pleasant land” still endures. Cream teas haven’t deserted multicultural Britain, nor have heritage-hungry tourists.

Did the prophets of doom who were at one time inclined to write off Britain as yet another has-been of history get it all wrong? Even if ‘Great’ may not have quite returned to Britain, has the UK averted becoming a case study in the science of ‘declinology’?

As with most such existential questions, the answers are bound to be tentative and hostage to either unanticipated developments, such as the disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, or to political upheaval resulting from, say, the secession of Scotland from the Union. However, some trends are unmistakable and linked to what Chaudhuri presciently saw as the “decay” that may have “penetrated the English mind”.

There is little doubt that the British identity is undergoing a fundamental reinvention. Some of it is the inevitable outcome of the most profound post-1950 demographic transformation the island has witnessed in its entire history. That today’s Britain boasts a home secretary, a chancellor of the exchequer, an industry secretary and an elected mayor of London who are non-white speaks volumes of the new UK. This visible cosmopolitanism is, quite predictably but unevenly, leaving its mark on the power structure and, more important, the social and intellectual climate of the land.

Thanks to its history as a trading nation and the experience of Empire, Britain has always had an acceptance of things foreign and a simultaneous suspicion of foreigners. The best of British universities combined a rich tradition of pageantry with an intellectual openness that, despite the relative paucity of resources compared to counterparts in the United States of America, have serviced the new knowledge economy well. My experiences in London and Oxford suggested a non-offensive, soft Britishness that, combined with scholastic rigour and a culture of irreverence, kept nearly everyone (apart from a clutch of uber radicals) reasonably happy. It is this delicate equilibrium, evolved through the traditional British muddle, that is in danger of being overturned.

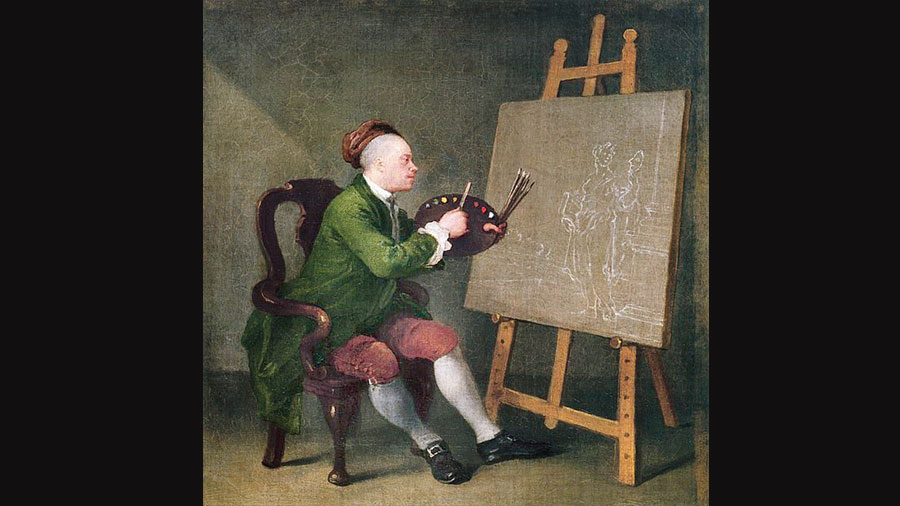

I got a small sample of this emerging Woke culture at the ongoing Hogarth and Europe exhibition at the Tate Britain. What was needless were the captions to the paintings of one of the world’s best social caricaturists. A ridiculous one was that which accompanied a self-portrait of Hogarth on a mahogany chair (picture). “Could the chair,” the curators asked, “also stand in for all those unnamed black and brown people enabling the society that supports his vigorous creativity?” To add to this over-interpretation, an entire section carried an alert to hyper-sensitive souls that there were paintings with racist overtones.

At least a great collection of Hogarth was on view. This week, the National Gallery released a report prepared by University College, London, that warned undiscerning visitors that a section of its collection, including paintings by Thomas Gainsborough and donated by William Wordsworth, was somehow linked to the slave trade. According to The Daily Telegraph report, Gainsborough painted two pictures of families whose wealth derived from the slave trade. Wordsworth, who presented a John Constable painting in 1837, has been included in the offenders’ list “because his sister’s rented cottage was leased by a slave-owner”. It is fortuitous that India’s Parsi philanthropists didn’t leave bequests to the gallery and further muddy the waters.

There is Woke outcry over a locomotive model from India that is displayed in the National Railway Museum in York and many students and alumni have demanded that the Seeley Historical Library (named after a famous Regius Professor of History whose books were widely read) in Cambridge be renamed because its present name “reflects the university’s historic and ongoing justification and support of colonialism”. The list is long, and its derivative is the ‘cancel’ culture that has witnessed academics being hounded out of universities and speakers disinvited for their views.

Reassessment of a country’s history and traditions happens in the natural course. However, when it is a consequence of a Maoist-style cultural revolution and a total repudiation of the national inheritance, there is cause for concern and counter-outrage. We can only hope that Woke politics doesn’t become an international export.