The English physicist, John Ziman, once complained that a scientist knows as much about science as a fish does about hydrodynamics. This does not mean it cannot swim. Only when the waters get polluted, swimming becomes a more self-reflective act. Science today, in its moments of crisis, is desperate for new concepts and ideas, which have the creativity and charisma to transform it into a new kind of knowledge system.

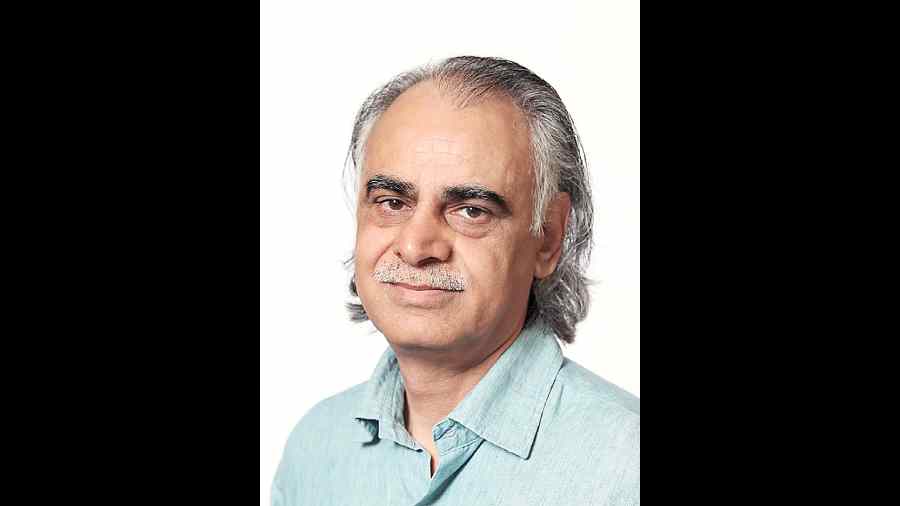

One concept that has the power to create an effervescence of ethics and creativity is the idea of post-normal science, elaborated in the writings of the South Asian scientist, Ziauddin Sardar. Sardar is a fascinating intellectual, a Pakistani physicist who has written one of the most engaging articles on the Ambassador car. More, as founder editor of Futures, he has helped create a cosmopolitan interdisciplinarity rather than a technocratic one-sidedness around the subject. As editor of Critical Muslim, he has shown the plural possibilities of Islam, demonstrating the theological illiteracy of the West. Sardar’s idea of the post-normal, which he elaborated with his commons of friends, including Jerome Ravetz, demands a salute and a detailed exegesis. The essays need a storyteller to drum them out in every village of knowledge.

The idea of normal science is based on Thomas Kuhn’s classic work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Kuhn explained that except in moments of crisis, science follows routine, predictable protocols of method based on a stable world. Only in moments of paradigmatic crisis does science become a more adventurous, imaginative affair. A textbook in that sense captures the diktats of normal science. It is of little help during a crisis. The idea of the post-normal initiates us into a world of everyday uncertainty, risk, chaos, complexity. It demands new methods and a radical change in imagination and attitudes.

One has to make two observations here. South Asia, in one sense, has always been self-reflective about Western science, especially during the era of the Indian national movement. For instance, few know that the idea of post-industrial society was coined by the geologist and art critic, A.K. Coomaraswamy. Daniel Bell gave it a second life in his best-selling book, The Coming of Post-industrial Society.

Patrick Geddes, the Scottish biologist, who wrote the first biography of J.C. Bose and discussed the idea of Santiniketan with Tagore, also coined the idea of a post-Germanic science. Geddes felt that at the beginning of the century, German science echoed with the sound of jackboots. Geddes wanted a non-violent, neo-technic science. He saw in J.C. Bose the first post-Germanic scientist and in Gandhi the first post-Germanic politician. Zia should be seen as a part of this genre of creative thinking.

One should also read post-normal science as a transitory affair, a conceptual and epistemic rite of passage waiting to be completed. In this period of temporariness, science has to be transformed into a new ethics and a new imagination. The Covid epidemic was an example of science repeating old perspectives when new thinking was desperately required. For Zia, the idea of denial or the sense of the emperor’s new clothes will not do. Science needs a new metaphysics. The idea of the post-normal is civilisational.

Almost like an obsessive housewife desperate to spring-clean, Zia lists out the problems of current science. It is a time of little confidence and less certainty, what Sardar calls a transition between two orthodoxies. This period is marked by uncertainty, chaotic behaviour, where the standard ritual of method does not work. Method has to travel beyond rigour. It needs to be exorcised of certainty to face complexity and contradiction. It chronicles a time when a predictable economy and a predictable nature have disappeared.

Zia’s comrade in philosophy, Jerome Ravetz, argues that a simplistic reduction of nature is over. Climate change is the classic example of this change. Nature is now seen as complex; it is beyond simplistic, reductionistic physics. In fact, one of the first casualties of post-normal science is ‘physics envy’. The worlds of efficiency and productivity also have to be abandoned for more supple concepts. Linearity and progress are as Victorian as contemporary science can get. One needs a new language of limits and new ideas of time to confront these new realities. Zia and Ravetz suggest that science, like modernisation, has become toxic. The cure lies in plurality and humility. John Sweeney’s labelling of physics as a “global weirding” reminds you of a need for new categories.

With the crisis of science comes the abandonment of the idea of the alleged superiority of Western civilisation. Sardar, like Gandhi, is suggesting that Western science would be a good idea. Zia is as playful and responsible as Gandhi. He once told me that the migrant in the world would rescue both Western civilisation and South Asia. He proposes, following the endorsement of Julia Kristeva, a polylogue of sciences, an interconnectivity of multiple epistemologies. Zia takes satyagrahic science to a new stage by confronting complexity and uncertainty. How do we react cognitively to what we do not know? How do we build ignorance into ethics?

Such an idea of post-normal science goes beyond current science. In fact, India’s leading scientific journal is called Current Science. It has an irony to it. A change in title would be traumatic and transformational for State and science in India. A new sensibility would add a touch of humility to science. One needs a creative ethics, which goes beyond the old etiquettes of science. Ethics has to confront the logic of alternative possibilities.

Sardar adds to it an old South Asian habit. The idea of the adda gets an epistemic twist honouring the polylogue. A polylogue goes beyond dialogue in acknowledgement of the multiplicity of pluralisms. A pluralistic epistemology for physics would change the pedagogic nature of the subject. Textbooks would be less didactic, and science could reclaim its old playfulness. Polylogues do not always demand unity and recognise that contradictions cannot always be resolved. The old world of dualisms, which sustained Enlightenment thought, dissolves. The scientist as polylogue engages with the new science no longer as an objective but as a conversation of epistemology and values.

One also has to recognise that the old definition of science as public knowledge no longer holds true. In fact, legislatively, a right to information also needs a right to knowledge and to alternative formulations. The new knowledge forums or panchayats have to be epistemically plural.

Sardar literally choreographs a new post-normal science. He insists that such a science is not merely a critique of ecology but also a search for new epistemologies. Science as a democratic enterprise recognises the power of alternative imaginations. This humbler science recognises its inefficiencies but still senses it has much to offer. Sardar, following the Australian philosopher, Paul Cilliers, emphasises the need for a new imagination. A new imagination that includes ethics and epistemology adds to a new imagination of democracy. By reinventing themselves, science and democracy become more life giving and open-ended.

(Shiv Visvanathan is an academic associated with Compost Heap, a network pursuing alternative imaginations)