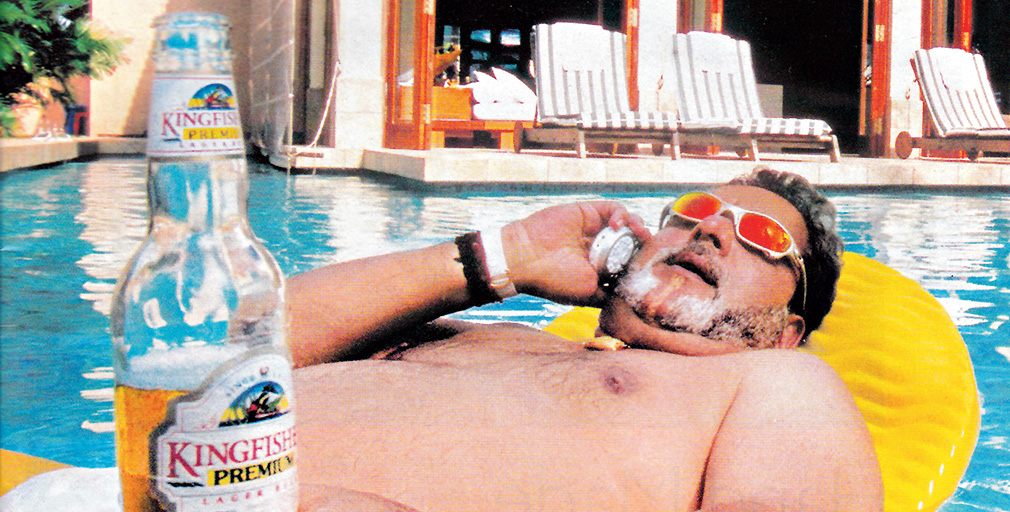

The cover of The Observer Magazine from the November 26, 2006 edition featuring Vijay Mallya. Scanned from The Observer Magazine

Narendra Modi may find this a little ironic, but Europe’s biggest gurdwara, the Sri Guru Singh Sabha in Southall in west London, stands on Havelock Road, named — like Havelock Island in the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago — after Sir Henry Havelock, the major-general credited with putting down the 1857 Indian uprising in Lucknow. So would Himmat Singh Sohi, a former president of the gurdwara but still a leading member of its governing committee, like to follow the Indian prime minister’s example and rename Havelock Road?

“Not so much of an issue here,” said Sohi. “Most of our people don’t know too much about Havelock. If we want to change the name, we would have to talk to the council.” One man who called Havelock’s record in India “obscene” and did try to change the name is the local Labour parliamentarian, Virendra Sharma. “That was 16 years ago when I wanted to change the name for someone with a local connection but I got nowhere.” So Sharma must support Modi’s decision to rename Havelock Island Swaraj Dweep? “Depends on what his motivation is,” Sharma responded enigmatically.

Havelock would have been proud of the military manner in which young Sikhs, equipped with sticks, baseball bats and ceremonial swords, stood ready to deploy when Britain was burning and looters were ransacking shops all over the country in 2011. Wisely, the looters did not risk an invasion of Southall. I had rushed to the gurdwara where Sohi told me, “Even if there had been 200 of them, we had 1,000.”

In spite of Modi’s best efforts, Havelock has not been expunged from history. There is an impressive statue of him in Trafalgar Square and dozens of pubs, rooms and public spaces are named after him in Britain and other countries.

Mrinal Sen at his residence after returning from Cannes Film Festival. The Telegraph file picture

Footnote

I began a New Year clear-up of old newspapers, press releases, clippings and general clutter gathering dust, but had to stop when I came across the cover story of The Observer Magazine from November 26, 2006 on ‘The new India’, with “an 84-page special issue on the world’s next superpower”. The cover illustration was that of the flamboyant tycoon who then best symbolized India rising: a reclining Vijay Mallya on the phone in a pool.

Last goodbye

A final word of farewell to Mrinal Sen, with whom I spent a few days when he came in 2010 to the Cannes Film Festival, where he was greeted with cries of “Bravo, bravo,” after his film, Khandahar, was screened in Salle Bunuel as part of the ‘Cannes Classics’.“I never expected such a large crowd,” he murmured as we came out.

The festival authorities had announced that “Mrinal Sen, one of Indian cinema’s greats, will be present at the screening”. He was in good company, for golden oldies shown in Cannes Classics that year included Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard; John Huston’s African Queen; Boudu sauvé des eaux (Boudu Saved from Drowning) by Jean Renoir; and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

After a tortuous journey from Calcutta, involving missed connections, a frail Sen arrived on May 14, 2010 — his 87th birthday. His son, Kunal (his “bondhu”) flew in from Chicago to look after him. But after a bracing walk in the sunshine along the sea side, a couple of agreeable meals with old friends and greeting the legendary film critic, Derek Malcolm, with a hug in the India Pavilion, Sen confided: “I feel I have been restored. I have been here so many times. Up to a certain point in time Cannes was my second home.”

He was on the main jury in 1982, along with the novelist, Gabriel García Márquez, who won the Nobel Prize later that year. Two of Sen’s films were shown in competition — Kharij in 1983 (it won the Jury Prize) and Genesis in 1986. Khandahar was shown for the first time in 1984 for the competition of Un Certain Regard. At an Indian party at the Carlton Hotel, I remember he was greeted by, among others, Abhishek and Aishwarya Bachchan, who touched his feet. One of Sen’s countless admirers, Souleymane Cissé, the distinguished Mali director, asked me to pass on a message: “Tell him he is my teacher.”

That some of Sen’s films were “overtly political and earned him the reputation as a Marxist artist” endeared him to the French elite and strengthened the Calcutta-Cannes connection.

Bad dreams

It is enlightening how English cricket writers assess the Virat Kohli-led Indian team’s triumph in Australia. “I cannot see Australia beating England this summer unless they assess themselves brutally,” predicts the former England skipper, Michael Vaughan, in the Daily Telegraph. “First series success in Australia makes up for defeat in England last year,” Scyld Berry suggests. “By winning 2-1 they have made up for their 4-1 defeat in England last summer.”

But only up to a point. India’s 4-0 and 3-1 defeats in the Test series in 2011 and 2014 respectively make a pattern. Some of us still have nightmares recalling Kohli’s last innings in England — a first ball duck at the Oval.

Ugly words

National newspapers employ women columnists on generous salaries partly because they can get away with making nasty observations about women in public life. Thus, Baroness Shami Chakrabarti, the shadow attorney general, came in for a very personal attack in the Daily Telegraph last week from Juliet Samuel for being soft on Labour in her report on anti-Semitism in the party before accepting a peerage from Jeremy Corbyn. She comments on Shami’s portrait holding a mask with her own face in the National Portrait Gallery: “Instead of the current label — ‘My mask is grim, worthy and strident’ — something along the lines of, ‘Underneath I’m cynical, self-obsessed and venal’ should do the trick.”