The Supreme Court was irked by a policy of the Madhya Pradesh government that incentivised the securing of capital punishment for public prosecutors. The court noted that such policies would undermine prosecutorial and judicial independence and fair trial. In 2015, the Bombay High Court had quashed a similar policy of the Maharashtra government that imposed a 25% conviction rate for eligibility for PPs. These astonishing policies raise two critical concerns: PPs’ interaction with the criminal justice system and executive control over PPs vis-à-vis independence of PPs in delivering justice.

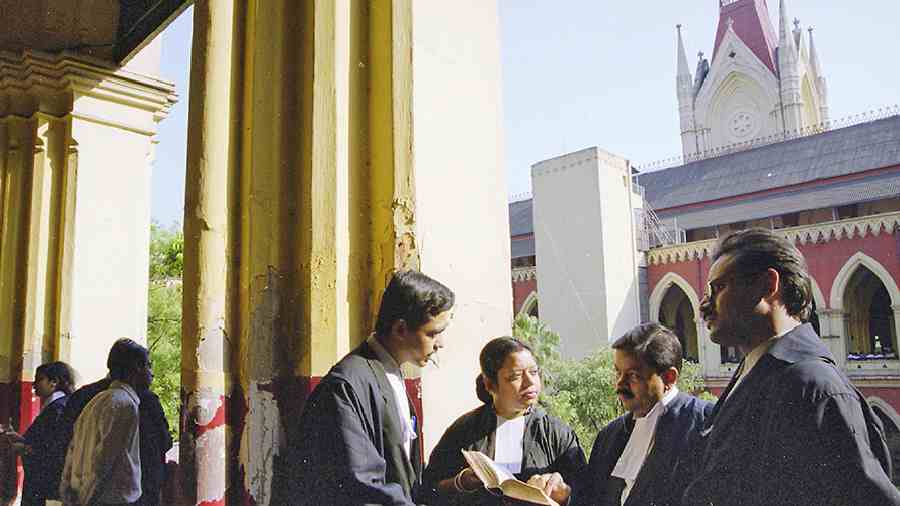

The SC and the Law Commission of India have affirmed that the role of PPs is to defend justice and act as an officer of the court. The LCI, in its 154th report on the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, quoted a Kerala High Court judgment referring to PPs as the “ministers of justice” with the task of assisting the State in the administration of justice.

The 2005 amendment to the CrPC led to the current standing position of law that introduced Section 25A, suggesting the establishment of a structured Directorate of Prosecution that is separate from the control of police agencies and falls under the administrative prerogative of the state governments’ home departments. Although this system is not entirely independent from executive interference, it still provides some autonomy for the functioning of PPs. Along with the presence of a structured Directorate, Section 24 of the CrPC acts as a safety valve. It mandates consultation of the judiciary with the executive for the appointment of PPs to curb excessive interference.

However, the appointment and promotion of prosecutors fall under the Concurrent List. It empowers states to amend the provisions related to prosecutors in the CrPC by introducing amendments. Many states have bypassed the normativity of the CrPC by introducing amendments averse to checks and balances. A report by the Vidhi think tank records that Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal have diluted the process of making a regular cadre envisaged under Section 24(6) of the CrPC.Furthermore, Karnataka has omitted the consultation requirement of the high court in the appointment of PPsand additional PPs whereas Uttar Pradesh has done away with the system of preparation of panels of lawyers by the district magistrate in consultation with the sessions judge, thereby defeating the purpose of the provision.

The checks and balances over the appointment of PPs, once bypassed, could lead to malfunctioning of the office. It is worth noting that the policies of the states indicate that convictions are confused with justice. Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh have endorsed the narrative of capital punishment to curb crime and that is evident from the manner of the functioning of PPs. Session courts in UPhave imposed 34 death penalties; the cumulative data for MP for the last five years is 62. A man was sentenced to death in just 46 days in MP —a display of the desperation of the PP to ‘persecute’.

A report by Project 39-Ahas cited instances of jeopardising fair trials by prosecutors in death penalty cases. It notes that lawyers having strong political connections often build formidable prosecution cases —even if it involves extracting statements through torture. Further, the data suggest that if policies related to PPsare arbitrary, they are likely to affect the marginalised the most. Incidentally, one in every three undertrials belongs to either the scheduled caste or scheduled tribe community.

Therefore, there is a pressing need to rethink the policies of appointments and incentives related to PPs. A system encouraging prosecutorial accountability, independence of the office of the PP and strict compliance to the safety valve in light of the observations made by the apex court as well as to the recommendations of LCI may reverse the damage that the current system has incurred.

Shaileshwar Yadav can be reached at @shaileshwar21