“The horror! The horror!”: these were the memorable last words of Kurtz, an enigmatic ivory trader, in Joseph Conrad’s novella, Heart of Darkness. Kurtz had gone rogue (‘gone native’) and lorded ruthlessly over a “devilish” fiefdom of Africans in King Leopold’s Congo. The young narrator, Marlow, a captain in Kurtz’s former trading company, witnessed first-hand the brutal savagery of Belgian colonial domination and became entranced with Kurtz’s ambiguous rebellion against it.

Marlow confesses to being faced with a terrible “choice of nightmares” as he is drawn to submit his loyalty to the more ‘honest’, but nightmarish, savagery of Kurtz rather than the naked hypocrisy of European imperialism, an imperialism based on systematic exploitation, steeped in the darkest of horrors, bearing the mantle of Enlightenment.

The Heart of Darkness is remembered by many Western intellectuals as the “epitaph of the entire 20th century and the West’s uneasy and exploitative relationship with Africa.” Yet, as we see in the near-apocalyptic bombing of defenceless Palestinians in Gaza as well as in the blood-curdling, indiscriminate slaughter of 1,400 Israelis that preceded it, the horrors of the 20th century are hardly behind us. Neither are the structural causes that precipitated them. The difference is that we now see it in images and videos in high definition, superimposed with running commentary. Moreover, we find that this fine-grained, troubling public consumption of televised massacres does not seem to rouse any shared human capacity for empathy. Often, the visceral experience of violence only serves to harden stereotypes and reinforce divisions.

For two weeks, Israel’s defence forces have rained down righteous fire on a tiny, besieged Mediterranean strip sheltering several generations of occupied non-citizens. Israeli analysts have long compared bombing blockaded Gaza to “shooting fish in a barrel”. Over 7,000 Gazans have perished so far; over a million have been displaced (roughly half of the population). Almost half of Gazans are children born into, as per the descriptions of the former British prime minister, David Cameron, an “open prison” or “prison camp”. Unicef has called the deaths of nearly 3,000 children a “stain on our conscience”.

In Israel and the War in the Balkans, Igor Primoratz studied the Israeli television coverage and popular reception of the early 1990s conflict between Serbian nationalists and Bosnian Muslims. Primoratz described how the Israeli media portrayed war crimes, such as the ethnic cleansing of the Bosnians, based on the (correct) assumption that its target audience would vicariously identify with the role of the oppressive Serbs. “Collective repression and denial of these facts [of Israel’s violent history of establishing a settler-colonial domination over the Palestinians] help explain the unwillingness or inability of Israeli society and its political establishment to condemn the Serbs’ war of expansion and ‘ethnic cleansing’”, wrote Primoratz. One leaves it to the judgement of the reader as to whether the testosterone-fuelled fixation on Israeli mass violence, on display on television and social media, and the freely-pressed justifications for dehumanisation form some kind of a ‘premonition of a nightmare’ that should fill one with dread. An increasing number of genocide and Holocaust scholars, such as Omer Bartov, Marion Kaplan and Raz Segal, are saying that we are indeed witnessing genocide taking place before our eyes.

The Western response has been atrocious. The United States of America has unconditionally backed its closest ally in the Middle East, not just bolstering the Israeli Defense Forces’ weapon supplies but also shielding it diplomatically. This included employing a crucial veto on a resolution in the United Nations Security Council that called for a ceasefire. On Wednesday, Joe Biden informed the world that he had lost confidence in the Palestinian-supplied death count. This was perhaps a clumsy attempt to hold on to the last vestiges of shame or, more cynically, an invitation to surrender to what Hannah Arendt called “animal pity”.

One can take some morbid relief in the fact that such Western behaviour is true to its historical form, especially during episodes of conflict in arenas of geopolitical interest. In 1975, the Australian ambassador to Jakarta, Richard Woolcott, advised his government to go along with the Indonesian invasion of East Timor, citing the compelling factor of exploitable oil reserves in the Timor Gap. The Indonesian military invasion, supported by Western arms and diplomacy, led to widespread bloodletting and, ultimately, turned genocidal, wiping out an estimated 2,00,000 people, almost a quarter of East Timor’s population. Woolcott had advocated his course as “a pragmatic rather than a principled stand,” noting “that is what the national interest and foreign policy is all about.” That statement, unfortunately, is still a fairly accurate descriptor of the strategic thinking of the Western Establishment.

“The well-being of the state justified whatever means” — Western Statecraft’s deathly doyen, Henry Kissinger, distilled it down in his book, Diplomacy. In The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide, Gary J. Bass, a professor of politics at Princeton, marshalled a wealth of sordid evidence describing the complicity of Richard Nixon and his foreign policy czar, Henry Kissinger, in the genocide of Bengalis that accompanied Bangladesh’s painful birth. The Nixon administration ignored the repeated warnings of its diplomatic officials and declined to intervene in the massacres committed by the Pakistani military, while stepping up the supply of arms and ammunition.

The White House’s decision-making in such an episode is, of course, theoretically presented as a cold, rational calculation of neutral interest: a realist approach towards maintaining the regional balance of power. But it was also quite clearly based on a stunning level of neo-colonial racism and an absurdly primitive view of South Asia. “Nixon and Henry Kissinger… were driven not just by such Cold War calculations, but a starkly personal and emotional dislike of India and Indians,” writes Bass. Both Nixon and Kissinger shared, to varying extents, the colonial-era, racist view that “Bengalis are not fighters” and, hence, “30,000 troops” of Pakistani military would eventually subdue the “75 million” people of East Bengal. Bass records Kissinger’s response to the news of the murder of a Muslim Bengali professor, a former student of his — “Henry Kissinger, seemingly referring to past Muslim rulers of India, replied, ‘They didn’t dominate 400 million Indians all those years by being gentle.’”

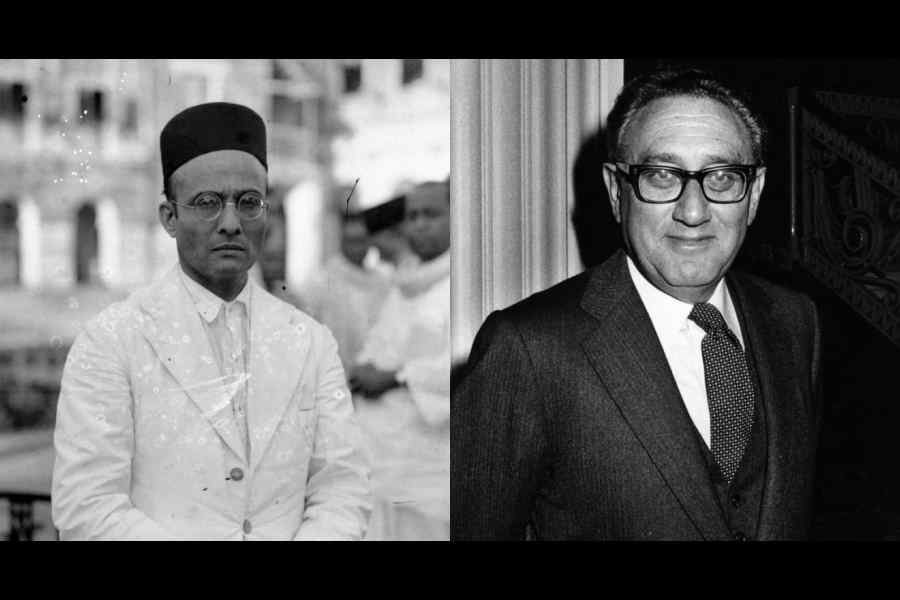

In Essentials of Hindutva, V.D. Savarkar launched a frontal attack on the “mumbos and jumbos of universal brotherhood” that was supposedly found in the Indian philosophy of history, especially relating to Buddhist passivity. “As long as the whole world was red in tooth and claw and the national and racial distinction so strong as to make men brutal, so long as India had a will to live at all a life whether spiritual or political according to the right of her soul, she must not lose the strength born of national and racial cohesion,” he wrote.

We can notice a striking similarity in the understanding of the human world in the two thinkers cited above. On South Asia, both Kissinger and Savarkar were heavily influenced by mythologised colonial historiography of Hindu and Muslim India. This makes not just for an archaic, impoverished view of history but also bad policy. The pro-Pakistan realist approach of the US, including sponsoring militant jihadism in Pakistan in the 1980s as an instrument of the Cold War, finally boomeranged in the 9/11 bombings, spurring further disastrous blunders. Pakistan’s realist approach of centralised, military-based foreign policy led to a resounding defeat, followed by the splitting up of territory.

Perhaps India can demonstrate in the future a better approach to realism and global conflicts. Of Gandhi’s romantic patriotism and Tagore’s humanist universalism, rejecting the deterministic framework of the Western nation-state; of peacefully carved linguistic states; of the ‘middle path’ of the ancient philosopher, Nagarjuna; of Madhyamaka Buddhism. India had shown the way in the past, not entirely for moral reasons, of course. But its principled stands on Vietnam and Bangladesh earned it enormous soft power and elevated its moral place in historical memory. Even if there is no foreordained global order, in a world of fast-increasing nuclear flashpoints, a socially constructed world of empathy and mutual understanding might just present some hope of salvation.

Asim Ali is a political researcher and columnist