Amit Shah, the president of the Bharatiya Janata Party, was clear. Pakistan returned Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman, the air force pilot it had captured after a dogfight near the Line of Control on February 27, within two days only because of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Shah told a campaign rally audience in Godda, Jharkhand on March 5. “That is the impact of this government,” he said. “They captured our pilot but had to release him within 48 hours only because of Modiji.”

The comments weren’t surprising, with the 2019 Lok Sabha election campaign heating up. Shah and his party colleagues will no doubt continue to trumpet India’s air strikes in Pakistani territory, in response to the February 14 terrorist attack in Pulwama that killed more than 40 Indian soldiers, as evidence of the BJP’s muscular nationalism in the weeks to come.

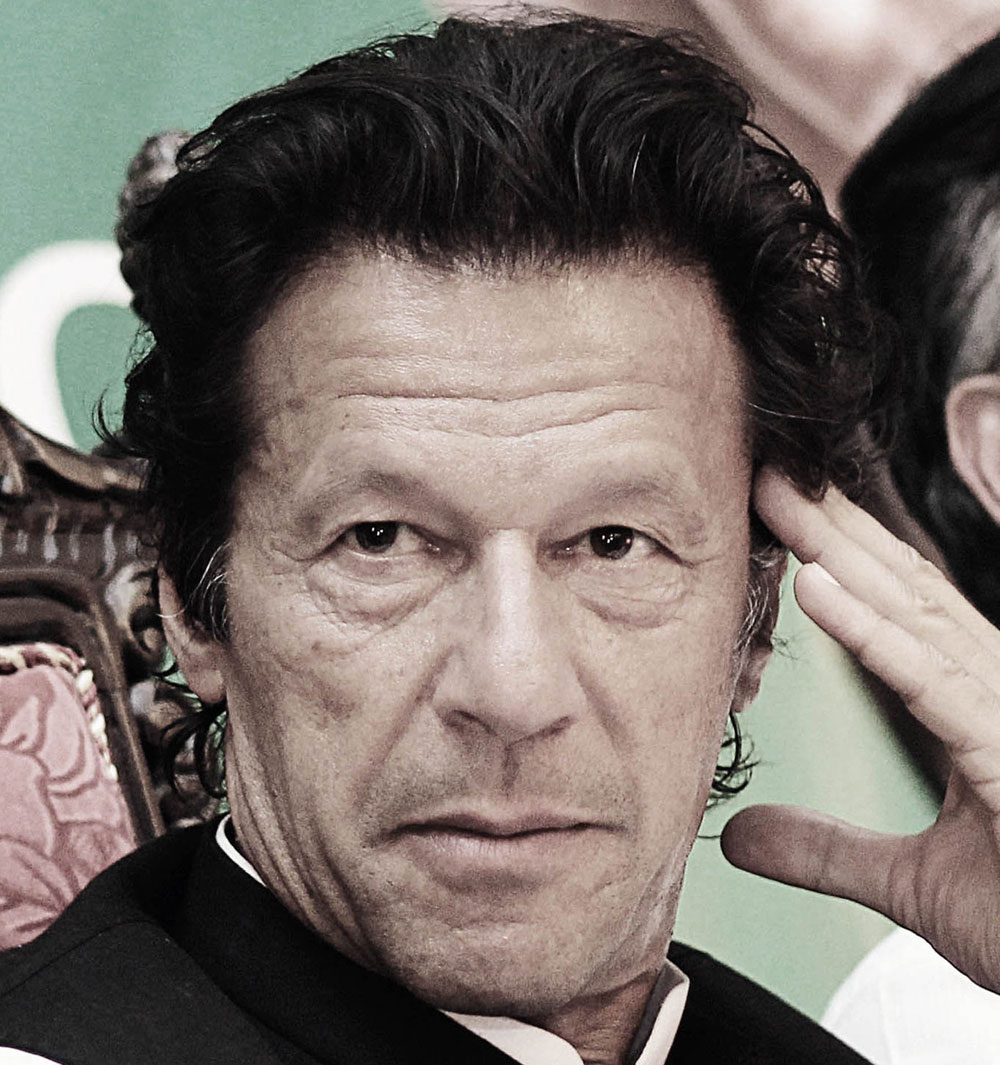

But to careful observers, the narrative that a Superman from Vadnagar rescued the Indian airman trapped in enemy territory was, sadly for Shah, exposed as a bluff even before Varthaman returned to India. On February 28, hours after the pilot had been captured, reporters in Hanoi asked the visiting US president, Donald Trump — he was meeting the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, there — about the heightened tensions between India and Pakistan. “[We have] I think reasonably attractive news from Pakistan and India,” Trump responded. “They’ve been going at it and we have been involved... Hopefully it’s going to be coming to an end.” A few hours later, Pakistan’s prime minister, Imran Khan, announced his intention to release Varthaman the following day, making clear what Trump had meant. Trump’s secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, and national security advisor, John R. Bolton, who had been speaking with both sides, had mediated Varthaman’s release.

In itself, having the United States of America lean in to help bring a captured Indian soldier back sounds good. But Trump’s comments, and those of others in his administration since the Pulwama attack , left little doubt that while the US empathized with India as a victim of terrorism, it’s primary goal in speaking to New Delhi and Islamabad was to bring down tensions. And while the US has played the role of mediator between the two countries several times in the past, this time, it is far from alone. That should worry India.

Saudi Arabia’s crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, visited Pakistan and India — in that order — in the immediate aftermath of the Pulwama attack. In Pakistan, he commended the country’s “sacrifices” in the war against terrorism, while in India, he agreed with Modi that there could be no justification for terrorism. Saudi Arabia’s junior foreign minister, Adel al-Jubeir, met the Indian foreign minister, Sushma Swaraj, in Abu Dhabi on the margins of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation conclave, and then, after visiting Pakistan on March 10, had a four-hour stopover in New Delhi on March 11, during which he met Modi and Swaraj. Such short visits and frequent meetings bear the stamp of efforts at immediate conflict resolution, not “follow-up” action on long-term strategic plans, as the Indian foreign ministry suggested.

The United Arab Emirate’s de-facto ruler, Mohamed bin Zayed al Nahyan, the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, telephoned Modi and Khan on February 28, and according to his Twitter post, stressed the “importance of dealing wisely with recent developments and giving priority to dialogue and communication.” He spoke to Modi again on the phone on March 11. On March 2, Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, said Turkey was ready to mediate between India and Pakistan. After Islamabad welcomed his suggestion, Erdogan dialled Modi on March 11 to discuss the simmering tensions.

For these countries, it makes sense to want to inject themselves into the India-Pakistan crisis. The US needs India to focus on balancing China’s rise, and Pakistan to help with enabling a deal with the Taliban in Afghanistan: a war in South Asia doesn’t help. The UAE and Saudi Arabia want Pakistan as part of their anti-Iran coalition, and want to wean New Delhi away from Tehran. Turkey, increasingly shunned by the West, is looking for new partners and markets. But for India, which has long rejected third-party mediation in its relationship with Pakistan — and still does, officially — all of this represents a tricky test.

At the moment, India’s fast-growing markets, its insatiable appetite for oil, and Pakistan’s duplicity with America in Afghanistan have made many of these international interlocutors tilt towards New Delhi more than Islamabad. And Modi does deserve credit for building on the West Asia outreach of his predecessor government to successfully juggle ties with Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Iran and Israel — no easy task.

But by allowing multiple countries to intervene in India’s relations with Pakistan, the government has allowed the weakening of New Delhi’s traditional posture against external mediation. That position is aimed at rejecting the notion of India and Pakistan as two hyphenated, squabbling neighbours, when New Delhi insists that it’s the victim of State-sponsored aggression from across the border. The strategic priorities of countries shift — remember, Pakistan was once central to Saudi Arabia’s financing of the mujahideen in Afghanistan.

Whether the nation has bought into the government’s post-Pulwama narrative will be clear on May 23. But whoever forms the next government had better stay prepared for a circus of mediators the next time things turn tense with Pakistan.