For the media industry, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s decade in power has been hugely transformative. There has been an extraordinary twinning of editorial emasculation and technological expansion, of gains for politicians, people and private capital, and losses — of freedom and viability — for the journalistic fraternity. There has even been a reconfiguring of the norms that the profession is expected to conform to.

Internet connectivity via mobile phones has empowered the poor. It has also put them within easy reach of no-cost political messaging. Shortly after the election of Narendra Modi and the BJP to power in 2014, Facebook promoted WhatsApp in India. Politicians now need the media less because they have found other ways to communicate with voters. Social media has helped diminish the political role of the traditional fourth estate. The prime minister came into office distrusting the media after his experience with them during the Gujarat riots of 2002. He found conventional media expendable and swept the polls after his first five-year term, during which he held no press conferences. He attended one called by his then party chief, but took no questions.

Today, for large parts of the Indian population, news media is a pesky side-show; what dominates their imagination are entertainment and cricket. If guards slumped in plastic chairs and manning the gates in our cities are hooked on both, it is because the other consequential M of this era, Mukesh Ambani of Reliance, ventured into telecom with Jio, was allowed to offer it free for over six months in 2016, and proceeded to catalyse an internet explosion that encompassed pretty much the whole country. India now has the second-highest population of active Internet users in the world. Apart from other international investors, in 2020, both Google and Facebook came on board as investors in Jio. Big Tech and telecom have now merged to enter the broadcasting sector in India with the launch of Jio Cinema.

The internet penetration rate in India went from 13.5% in 2014 to 52.4% in early 2024, an over threefold increase in 10 years. The Economic Times reported in 2018 that Jio’s inaugural offer racked up 100 million subscribers in 170 days. Subsequently, other telecom operators dropped tariffs in order to compete, helping deepen internet penetration in the country.

As for editorial emasculation, the first couple of months after the BJP’s election to power in 2014 saw the advent of private censorship when Amit Shah was elevated to the post of the party president. DNA first published a piece on Shah’s past record by Rana Ayyub titled “A new low in Indian politics”, and then scrambled to take it down from its web edition after the headline, in particular, reportedly riled the proprietor. A TV channel and a few publications also decided to omit references to the criminal charges that Shah was facing. If private censorship happens at the behest of an owner, self-censorship follows when other media houses choose not to report incidents of private censorship.

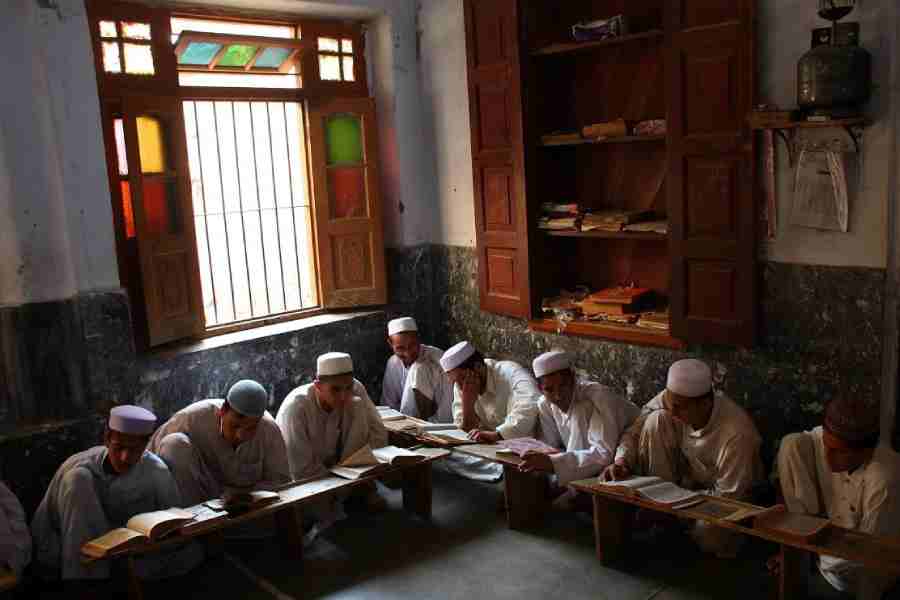

Over the years of this BJP-ruled decade, private censorship, self-censorship and legal intimidation have all come to stay. Government intimidation via the levelling of sedition and terrorism charges has acquired menacing proportions. Since May 2014, when this government first came to power, the 404 error page on media websites has been showing up rather more frequently than before. Facebook posts, too, have acquired the status of major unlawful activity, attracting charges of sedition or those under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. The UAPA was amended in 2019 to allow the government to proscribe individuals as terrorists. In 2020, a Kashmiri photojournalist who covers women and children in conflict was charged under the UAPA for uploading a photograph that allegedly glorified ‘anti-national activities’.

The notion of the media’s freedom to function is now negotiable, rather than absolute, with the courts taking dismaying positions at times. The Allahabad High Court, for instance, denied bail to Siddique Kappan in 2022 in a UAPA case because the judge accepted the prosecution’s contention that Kappan was a resident of Kerala and had nothing to do with the incident in Hathras and had deliberately, with mala fide intent, come with the co-accused persons and was arrested at Mathura. Does a journalist then not have the freedom to report or investigate news from any part of the country?

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act passed in 2023 allows the Union government to censor content on vague and unspecified grounds in public interest. By mandating consent for publishing personal data, it ensures that material unfavourable to the data principal would simply not get published. The Act also unreasonably widens the scope of exemptions available to public information officers of government ministries and departments to reject Right to Information applications on the basis that the information sought “relates to personal information” (Clause 44(3)(j)). Further, the Data Protection Board that the law provides for is problematic because all its members

will be appointed by the Union government (Clause 19(2)), putting its independence in doubt. It has been noted that the Digital Personal Data Protection Act started out with the European Union version as a model but ended up sounding like the Chinese version.

Regulators have now become fringe players in this landscape, counting for little when consolidation has to be regulated or small players protected. The Competition Commission of India has chosen not to support the news media so far on the anxiety-inducing issue of dealing with Big Tech platforms. Platforms are not sharing revenues adequately. While some countries in the Global South have got the backing of their governments and competition commissions to negotiate with Big Tech, Indian news publishers have not. The Competition Commission of India and the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal had brought Google to the table on anti-competitive conduct in the Android ecosystem and got it to pay a fine of Rs 1,337 crore. But publishers’ bodies in the country have been waiting since early 2022 for a ruling on their submissions about unfair terms from platforms that feature their news in search results and have found little joy.

Now, of course, the CCI will have an upcoming challenge in the humongous Reliance and Disney joint venture that is being finalised. The two will join hands to create a Rs 70,000-crore media giant with around 110 television channels in multiple languages, two leading OTT streaming platforms (JioCinema and Disney+ Hotstar) and a viewer base of over 750 million across the country. After the Modi government’s emasculation of the news media, the Reliance footprint looms even larger in the nation’s imagination.

Sevanti Ninan is a media commentator and was the founder-editor of TheHoot.org