Indians in Britain used to joke in the 1950s that the acerbic V.K. Krishna Menon thought the English had to be very developed since everyone spoke English. Given the quality of education in India, that definition is likely to prove elusive even if Narendra Modi’s promise of a developed country by 2047 is realised. Development is the mantra of our age but it often seems to mean no more than politically-backed promoters and contractors making fortunes by trampling on nature and aesthetics to create concrete forests of ugly vertical slums.

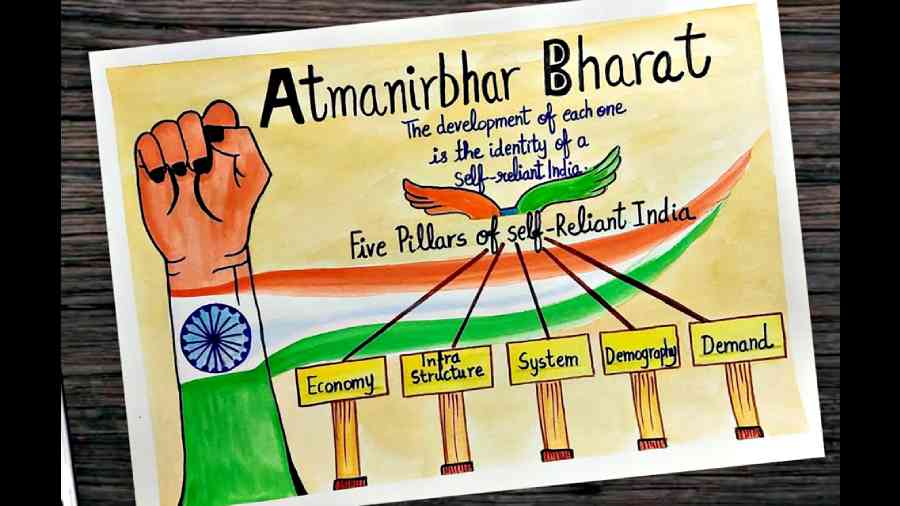

The Bharatiya Janata Party government inherited that legacy. In fact, with the notable exceptions of secularism and socialism, almost the entire corpus of India’s social and political phrases and practices was shaped and bequeathed by the Congress pioneers whom BJP stalwarts love to deride. The youth dividend that Modi doesn’t mention so often nowadays was also a Congress discovery while atmanirbhar is only desi for Jawaharlal Nehru’s import substitution. It’s one of the many old ideas recycled to suggest new thinking. The fervour with which this Mark Two import substitution was launched indicates little discernment in examining either its origins or why an initially commendable concept eventually came to be regarded as wasteful and counter-productive and is now sometimes farcical. I was sent a video of an admiral in full-dress uniform, replete with ceremonial sword, hoisted into a bedecked palanquin under showers of flowers to the cacophony of what looked like one of those foo-foo bands used for cheap marriage parties. Apparently, that private supplement to the formal pipe band and Auld Lang Syne ritual was also atmanirbhar.

Imitativeness is equally marked in foreign policy with India’s position on Ukraine inviting comparison with the non-aligned practice of running with the hare and hunting with the hounds, even if politeness forbids disparaging a potentially major importer. Even Modi’s romance with Israel began with Nehru playing footsie with David Ben Gurion followed by P.V. Narasimha Rao’s more sophisticated courtship of New York’s rich and influential Jewry. Modi’s ebullience makes fawning on Bibi look like an innovation.

Little that is of substance differentiates the two regimes. Apart from style, the BJP’s distinctiveness lies mainly in two spheres. First, the brisk efficiency of certain administrative departments under its direct control is in marked contrast to what we think of as traditional bureaucratic inertia. Second, the complexion and characteristics of a bunch of unofficial organisations comprising the sangh parivar combined with the rhetoric of its propagandists lend substance to the view that the party’s only ideology is rejection of secularism reinforced by a lusty majoritarianism. As for the economy, knowing that Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani would never have lit the skies so brilliantly if Manmohan Singh had not abolished wealth tax in 1991, the BJP has not deviated from the precedents set by the United Progressive Alliance. It has only taken those policies much farther. Even the discrimination that Muslims complain of was a feature of Congress times; it is reportedly more harsh and widespread now with the law enforcement forces often markedly unhelpful.

As the principal source of ideas, the Congress might therefore have had a chance at its Raipur plenary of again setting the nation’s agenda. It could have emphasised there that with the middle class additionally reeling from the destruction during the pandemic of around 15-20 million manufacturing jobs, India faces two options. One is the creation of a welfare State like post-Second World War Britain; the other the facilitation of universal and equitable wealth creation as in today’s Germany. Either can achieve the Congress (and, presumably, also BJP) goal of not only growth but also growth that benefits the poorest. “We believe workers have made our country; we should secure their rights and provide justice to them.” And, indeed, Raipur’s economic resolution promising “a safety net for the urban poor” was a step in the right direction. So was the proposed legal guarantee of healthcare services for all through an equivalent of Britain’s 1948 National Health Service Act with 3% of the GDP committed to healthcare. Raipur promised programmes on unemployment, poverty eradication, inflation, female empowerment, job creation and national security. But when it came to an overall long-term vision, the Congress seemed to dilly-dally, shelving the publication of a coherent document with specific measures to sometime in the unspecified future.

Not that India needs any addition to its surfeit of already voluminous verbiage. There is absolutely no need either for mammoth statuary or the extravaganza of what amounts to a new capital city. Singapore (where this is being written) has done very nicely with a per capita GDP of $109,330 adjusted to purchasing power parity without changing a single street name or removing a single colonial statue. Jagat Mehta, a former Indian foreign secretary, called the island republic “the only former colony to make a success of independence.” Not only did Lee Kuan Yew hold that atmanirbharta was unnecessary but he also ranked it foremost among the four factors — the others being a preoccupation with fair distribution, economic populism and the public sector — responsible for stagnation.

Lee credited his achievement to 30 years of reshaping the administration into an effective instrument to plan and execute policies. The young were educated during those years in one common language (Krishna Menon’s famous tribute to English) and the infrastructure revitalised. Those decades also witnessed a huge expansion in manufacturing, the services, banking and finance, telecommunications and tourism. Flushed with success, Lee proudly called the second volume of his autobiography, From Third World to First, pre-empting the journey Modi hopes India will make in another 24 years. Lee explained his boast to an India International Centre sophisticate who had commented on Singapore’s obsession with money. Taking the bull by the horns, the unapologetic premier argued that Singaporeans who lived in hovels with a hole in the ground for a toilet 20 years earlier but now owned two-million-dollar homes were understandably nouveau riche. “I would like to believe that in the next twenty-thirty years as we become ‘old rich’, we will acquire the graciousness that comes with a cultivated society.”

Whether or not that happens, several observers have lamented that India’s globalisation means journeying in the opposite direction — from sublimity to vulgarity. Marion Barwell, an Englishwoman whose husband practised at the Calcutta Bar, and who lived and died in India, lamented the cheap popular culture of the West that most Indians emulate. Endorsing that charge many years later, Nirad C. Chaudhuri noted a sharp fall from “the higher forms of Westernization which had been the main cultural expression of Indian life during British rule”. This is a New Delhi woman’s “craze for foreign” that V.S. Naipaul mocked when he also made fun of Calcutta’s “Jamshed into Jimmy” syndrome. More money means more tawdry pretension.

India is at the crossroads. Unemployment is soaring. The young who can vote with their feet by emigrating in hordes. A recent medical survey showed that the country lags behind in 19 out of 33 indicators relating to poverty, hunger, health and gender inequality. Other reports indicate that more than 3,000 tariff increases have affected 70% of India’s imports. There are yawning trade deficits, especially with China. The 11 trade agreements signed during Manmohan Singh’s 10 years as prime minister have not been matched in the nine years since. It is doubtful if the Hindenburg Research report will encourage foreign direct investment despite the carrot of a $27 billion subsidy New Delhi is dangling before companies like Tesla. The enemy is knocking at the northern door. New atmanirbhar innovations threaten to erode social stability. If, nevertheless, today’s India appears to be booming, that is largely because, as Manmohan Singh put it, his successor is “a better salesman”.