Few could be as contrary as Nirad C. Chaudhuri, who was born 125 years ago on November 23.

Diminutive.

And mammoth.

Pocket-sized and monumental.

Of the very essences of India, and of the effervescences of Britain, or what he believed to be Great Britain.

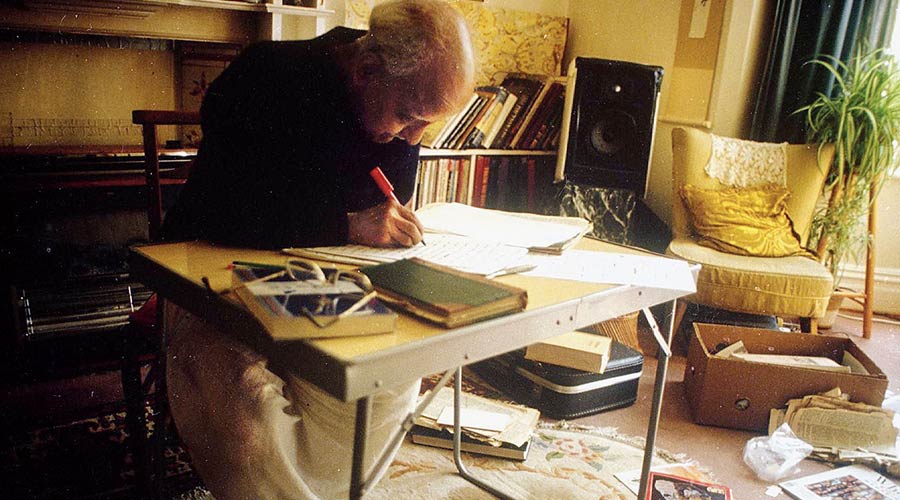

Attired, very deliberately and very often, in his years in Oxford (1982-1999), in the foppish style of an eighteenth-century Englishman of Means, he seemed to feel at home in those clothes. Perhaps he did not realize that they looked like they have come out of a shop dealing in period apparel. Perhaps he did realize that but just did not care. Perhaps he did not realize that his friends who numbered less than his critics were troubled to see this polymath allowing the oddity of his staged appearance to all but eclipse his genius. Or perhaps, again, he simply did not care.

Staged appearance, I have said. That is exactly how it was when, in 1992, I first encountered the great man. I rang the bell at his brick-lined, two-storeyed 20 Lathbury Road home in Oxford in utter nervousness. I had gone there by a carefully made appointment, needless to say, and was as punctual as the clock’s hands require. No chances to be taken with the author of The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian which I had read line by line in sheer awe, of A Passage to England in sheer rapture, of The Continent of Circe in total fascination, of Scholar Extraordinary (his biographical study of Max Mueller) in total mystification, of Clive of India, in what can only be called hundred per cent immersion, of Thy Hand, Great Anarch! without understanding one word of it!

But how was I to greet him? With an overwhelmed pranam, as I was inclined to? Or a more formal namaste? Or just a ‘Good afternoon, Sir’? I was a fool to be contemplating these alternatives in the protocol of courtesy. For when the white wooden door opened, I was in for a surprise or, rather, shock. I cannot say Niradbabu opened the door for me for it was Niradbabu, of course, and, yet, it was not Niradbabu. My host was dressed for what could be an Ivory-Merchant film shoot in a manor in the Lake District in the most formal attire I had seen in Britain. He did not smile. He bowed, with his right arm brought to his waist in a manner I would have associated with a Jeeves archetype, and said expressionlessly, “May I take your cloak and cane?” Now I had no cloak or cloak-equivalent, nor any cane or cane-type of anything, to hand over to the outstretched palm. I just mumbled some drivel and stepped in. The ‘play’ continued for some minutes, as I was asked to ‘Pray, be seated.’ I did not know quite what I was supposed to do. I could not have reciprocated by acting the role of an Indian visitor to Nirad C. Chaudhuri Esquire without looking an idiot. Nor did I want to break the spell that he had created — lest I somehow offend or enrage the Master. It was after several minutes of embarrassed mumblings punctuated by long pauses that the act gave way to ‘normal’ conversation. He spoke with passion and formidable knowledge about guns and rifles and pistols. The Mauser seemed to interest him particularly. I, of course, was totally at sea. Talk turned then to Mrs Chaudhuri who was in her room on the first floor. Niradbabu asked me to “go up and meet her,” which I did.

I could have been meeting Amiyadebi in Ballygunge or Bhowanipore. She was seated in a comfortable chair, reading a book. Smiling beatifically, she placed the book to a side and put me completely at ease. She talked about life in ‘cold’ yet comforting Oxford, her getting everything she needed to cook Indian food, ‘his’ non-stop absorption in ‘work’.

Two worlds. With ‘him’ at its centre. And ‘her’ being the still centre of that centre.

On subsequent visits, it was a relief to see him as Niradbabu. Clad in dhoti-kurta or dhoti-panjabi as the set is called in Bangla, a soft shawl draped over his tiny frame on which rested that bulbous dome of his head. What a library was housed there — in Bangla, English, French, Sanskrit, Latin, Persian and, as I found from his rivetingly-written “A Historical Perspective” to Linguasia’s 1994 edition of Henry Yule’s Hobson-Jobson (1886), in Hindi and Hindustani as well. For sheer brazenness in the descriptions of ribald specimens of that genre, the essay is not to be equalled. I doubt if any Indian publisher would venture to publish or re-publish it. It is hilarious and in great part risqué. Nirad Chaudhuri has enjoyed himself, writing that piece.

There was an event at the Nehru Centre, London, around the book. My wife had arranged for Niradbabu to join us for lunch, after the programme, in our flat above the Centre’s hall. To my “Sir, may I offer you a glass of wine?” he reacted with, “What is that? Glass of wine? You do not offer a glass of wine. You should ask whether you might offer a drink, giving the precise name of the wine, white or red, or as an alternative, cider, or beer, then again, ask if it might be lager or draught... not some glass of wine...” I was then quizzed about the Sanskrit for ‘mango’ and the difference in Urdu between be and ba.

To a casual observer, all this would have seemed like ‘showing off’. It was, in truth, nothing of the kind. Nirad Chaudhuri was the very personification of learning. But of a learning that was its own fulfilment, its own destination, journey and climax. A learning because it was so un-tied to a ‘subject’, a ‘discipline’, a ‘curriculum’ that it was an orphan in our programmed world. In ancient Greece, Nirad Chaudhuri would have been surrounded by fawning students, in old Persia by a host of besotted murid. In Nalanda of yore, by novitiate monks intent on mastering grammar, syntax and prosody at his feet. But he was in a world that was too late for him. Too impatient, too much in a hurry for knowledge to have time for his cargo of wisdom.

And so a cultivated mock-staginess became for him a substitute for natural recognition. He impressed and then amused a world which should, in truth, have allowed itself to be moved by him, moved by the parching of his scholarship in the drought of a discerning appreciation, moved by the blanching of his intellectual passion in the frost of academic neglect.

And there was the personal saga.

When Amiyadebi passed on, in 1994, some of us, not too many, drove to Oxford to be with him. “I have never in my ninety-odd years,” he said to me, “ever seen a person die... Her’s was the first death I was witness to... And I was alone in the house...”

Alone.

I can never forget Niradbabu peering through the hearse’s closed glass windows for a last look at his life’s companion.

But I cannot end this tribute on a sad note.

On his birthday the following year, I was at 20 Lathbury Street again, with friends — Srabani Basu and Dipankar De Sarkar — to celebrate this mental and human phenomenon. Four days later, I got this letter from him (I give excerpts): “Dear Mr Gandhi, I can hardly tell you how happy I felt to have you among those well-wishers... I repeat to you... a few lines from Shelley which will perhaps better express my feelings than any words of mine could — Rarely, rarely, comest thou...// How shall ever one like me/ Win thee back again?/ With the joyous and the free/ Thou wilt scoff at pain…

Nirad C. Chaudhuri and wit have gone together. So have Niradbabu and pain.

Pranam, Great Master.