Pitch parallel

The favourite of the Tory leadership, Boris Johnson, has compared himself to the English all-rounder, Ian Botham, thereby poking fun at Prime Minister Theresa May who had famously likened her style of governance to the batting style of Geoffrey Boycott, who “got the runs in the end”. “If I may venture a cricketing metaphor,” declared Boris, “I think we’ve had quite a lot of Boycott on the wicket and it is time for Botham to come in.” Botham had once allegedly run out Boycott in a Test against New Zealand in Christchurch in 1978 for “slow scoring”, just as Boris ‘ran out’ May from 10 Downing Street.

Hefty sums

When we moved to England, my father received a modest salary as head of Bengali service at BBC Bush House. He would be staggered at the salaries being paid today to senior BBC journalists, which have been published because women have pushed for parity with the men. Take, for example, Amol Rajan, the BBC’s Calcutta-born media editor, who gets between £2,00,000 and £2,04,999, while Reeta Chakrabarti, who is excellent as a television correspondent and analyst, receives between £1,70,000 and £1,74,999.

Ahead of them is Mishal Husain — of Pakistani-origin — one of the presenters on Radio 4’s Today programme who is in the £255,000- £2,59,999 bracket. The Sri Lankans are on top. The TV presenter, George Alagiah, is on £3,15,000-£3,19,999, while the very engaging Nihal Arthanayake, who has his own radio show, is on £1,75,000-£1,79,999.

But even in this day and age, they are a long way behind the football presenter, Gary Lineker, whose figures are £17,50,000-£17,54,999.

Painful memories

Most of us are familiar with the accounts of communal violence from the time of Partition. What Kavita Puri has done is collect stories from Indians and Pakistanis who are now living in the United Kingdom but were children in 1947. Kavita, who first told their tales for a series on BBC Radio 4, has included them in Partition Voices: Untold British Stories, which has been published by Bloomsbury in the UK and is just about to come out in India.

She begins with poignant reflections on her own father, Ravi Datt Puri, as she scatters his ashes into the Ganges at Haridwar. He was 12 at the time of Partition. “Born in Lahore, Pakistan, an adult life lived in England, he now rests somewhere along the most sacred and blessed river in India,” his daughter writes, commenting later, “[t]his book has become much more personal than I ever intended.”

Like so many others, Kavita’s father kept silent for 70 years about the horrors he had witnessed, opening up only towards the end. As the author says, the time window on their first person accounts is now rapidly closing. The point made at Kavita’s book launch was that Partition constitutes not only the history of India and Pakistan but of Britain as well, and should be included in the school syllabus.

What I especially like about Kavita’s book is that she has also included interviews with British people who bore witness to Partition. For example, there is a photograph of Pamela Dowley-Wise as a teenager on her bicycle in Calcutta, the city where she was born. She has harrowing memories of the Bengal Famine of 1943. “It felt terrible, Pamela says, eating her evening meal knowing what was happening outside.”

Pamela was pushed off her bike in 1946 during the Quit India movement. She is now 91 years old, and runs riding stables in Surrey, but has returned to India often and “always retained her love for the country”.

Footnote

Visiting Tate Britain for one of the best exhibitions in London, Van Gogh and Britain, makes you appreciate how much more there is to the artist than sunflowers. There are several stunning landscapes and self-portraits, but the exhibition does end with a signature study of sunflowers. Vincent van Gogh lived in London from 1873 to 1876, and influenced and was influenced by British artists. I also learnt that he was inspired by Charles Dickens and read all his novels.

Boris Johnson has compared himself to the English all-rounder Ian Botham. Telegraph file photo

Back in time

Something “quite extraordinary and wonderful” happened in Calcutta in 1922, I am informed by Sundaram Tagore, an influential figure in the world of art who owns galleries in New York, Hong Kong and Singapore. Having completed his documentary, Tiger City, on the American architect, Louis Kahn, Sundaram intends to make a film on the landmark exhibition held in Calcutta in 1922 by the leading avant garde artists from Germany’s Bauhaus movement.

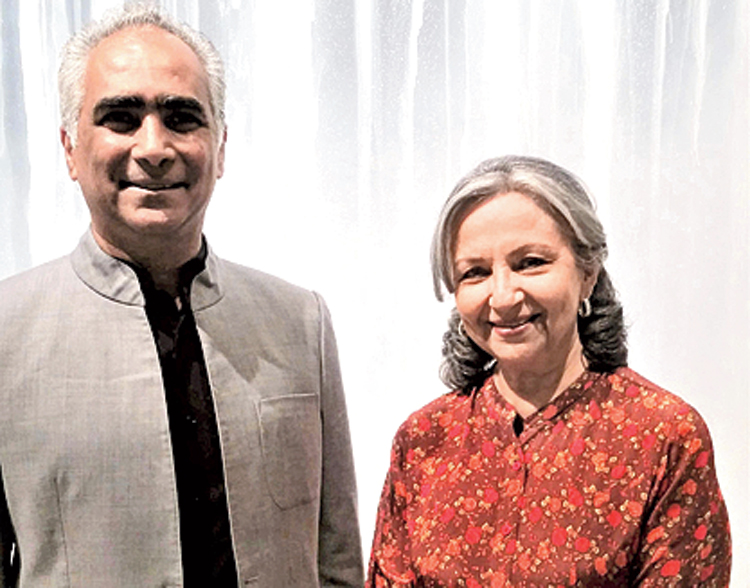

I catch up with Sundaram at Masterpiece, an exclusive London exhibition where he has brought the very best of “East meets West” art, represented by the likes of Vasudeo S. Gaitonde (India), Anila Quayyum Agha (of Pakistani-origin), Tayeba Lipi (Bangladesh), Hiroshi Senju (Japan) and Zheng Lu (Inner Mongolia). At one point, Sharmila Tagore dropped by to say hello.

At one point, Sharmila Tagore dropped by to say hello. Telegraph picture

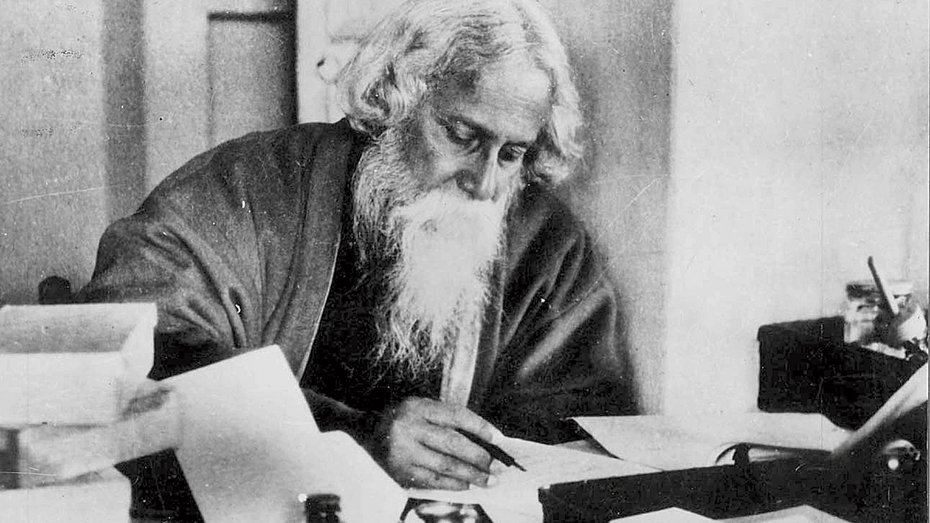

The 1922 exhibition, of some 250 works of art, was held in Samabaya Bhavan behind the Park Hotel in Calcutta, says Sundaram. “I am interested in the confluence of cultures and this exhibition happened because Rabindranath Tagore was there.” The art historian, Professor Partha Mitter, whom Sundaram is to interview as part of his film, answers my question: “Why Calcutta? Without a doubt Rabindranath Tagore’s global reputation had a lot to do with it. This is the centenary year of the Bauhaus and I have contributed essays in exhibition catalogues comparing the teaching methods of the Bauhaus and Santiniketan.”

“Bauhaus was arguably the most important movement that shaped global modernism. Inspired by Rabindranath Tagore and actively organized by Stella Kramrisch, an exhibition of the works of Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Johannes Itten and other members of the Bauhaus School of Design and Architecture was held at the Oriental Society of Indian Art in Calcutta in 1922.”