Many believe that the name Kolkata is actually derived from the Dutch form of the word golgota, which is often used to refer to a place where the bones of the dead are stored. The grim picture aside, the influence of the Dutch in Bengal still remains in the form of relics, graveyards, buildings, churches and even language.

In the town of Chinsurah, about 75km by road from Kolkata, there is a spot that offers a peek into Bengal’s connection with the Dutch. It is the Chinsurah Dutch cemetery.

The Dutch in Bengal

A masonic work with royal Dutch motifs; Dutch East India Company used European currency instead of the rupee. These coins were primarily used in Indonesia, and sometimes used in India too Somen Sengupta; Shrayan Bose

Before the British East India Company, the Portuguese, French and Dutch counterparts travelled to India with the objective of setting up trading posts and businesses. Unlike its counterparts, the Dutch traders tasted limited success in the country, mostly in the south and in some parts of Bengal.

The Dutch East India Company, officially the United East India Company or Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie was founded in the early 17th century. Trade with Bengal began in 1615, and soon a trading post was set up along the Hooghly in Chinsurah to trade in spices, cotton, and opium. The Dutch remained until 1825 until they had to hand over the province to the British.

Through the 1600s and 1700s, for about 150 years, the Dutch remained in India and in Mughal Bengal. They expanded their business to Cossimbazar and Chinsurah, happily coexisting with the Armenian community, who also had a presence in Chinsurah during the time.

History in stone

The cemetery is an ASI-protected site Somen Sengupta

A walk inside the walled compound of the Dutch cemetery in Chinsurah opened new doors to the history of colonial Bengal, which goes much beyond the British. It is worth noting that this cemetery is reportedly the biggest non-British European cemetery in West Bengal, making it bigger than Kolkata’s Scottish and Greek cemeteries.

The 7,400-odd square metres has 190 graves, dating from 1743 to the end of the 19th century. Apart from the graves of Dutch settlers, there are a few of local Britons who came when the British overtook the city towards the end of the 19th century.

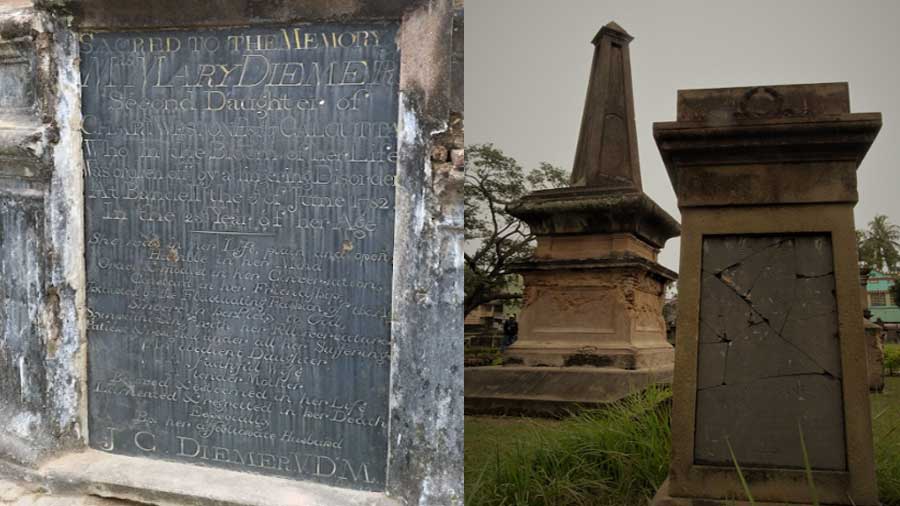

The similarity in the architecture of the cenotaphs with those in the Dutch cemeteries in Tamil Nadu and Kerala are striking. The monuments are mostly brick, with black or white marble headstones and epitaphs. Until recently, site was in need of some care and protection from unruly visitors, but now as a protected Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) site, it has been given a facelift.

Having a guide who would be able to tell the significance and stories of many of the graves is always advisable.

Buried secrets

The epitaphs on many of the graves have information about the deceased Somen Sengupta

Among the many interesting things to be seen at the site, is a beautifully crafted metal shield fitted to one of the graves. It is a stunning observation, how many of the deceased resting here died young – many before the age of 20 and some as children or infants. The epitaphs give the names, and sometimes little anecdotes, of the ones buried here.

Henry Allen Herklots, died in 1830 as a five-day-old baby, while Alphonse Lacroix died in 1828 aged six months and 22 days, and R.W Hessings died in 1806 at the age of three years and 22 months. One Henry Donnithrone, who was the son of a foot soldier, died in 1843 at the age of 14.

Most of the Dutch officers who served as governor have found a resting place on these grounds – Peter Vuyst, Jan Albert Sicherman, Abraham Patras are among the few names.

Daniel Anthony Overbeck, the last Dutch Governor of Chinsurah, who stayed in the town even after the region was handed to the British, also rests here.

The cemetery has many uniquely designed cenotaphs Somen Sengupta

The oldest grave is of a man named Sir Cornelius Jonge, who died in 1743. As the present site of the cemetery is not the first in Chinsurah, it is unclear if he was originally buried here or shifted from an earlier resting place. It is assumed that the present address dates back to sometime between 1754 and 1755, however records by Dutch navigator Admiral Jan Splinter claim the existence of the old cemetery in the 1770s.

The website dutchcemeterychinsura.com, which was an initiative by Presidency University scholars, and funded by the Embassy of The Netherlands, to record Dutch history in Bengal, lists other little-known stories from the site.

The cemetery is the resting place of many Dutch officers Somen Sengupta

The tombstones of many of the graves are either difficult to read or illegible, and some have even been removed. The historical documentation of the Dutch in Bengal was not well managed until a few years ago when the university and the embassy started the initiative to preserve the legacy. The job was completed a year ago and the digital resource now archives records and photographs from the time the Dutch arrived in Bengal to their gradual fall.