I am sure you have heard of the name Giacomo Girolamo Casanova, the 18th-century adventurer from Venice who earned notoriety for his amorous exploits so much so that the moniker of casanova has come to be used synonymously for a person with little or no scruples as far as romantic liaisons go.

Did you know, though, that one of Kolkata’s well-known locations has a link to this Italian swinger?

Let’s roll back to about 250 years ago. Sometime in the 1770s, a man from Venice arrived at the Calcutta docks. His name was Eduardo Tiretta, or more precisely, Count Tiretta de Trevisa. The count was a partner in crime of the (in)famous Casanova. In the book The Memoirs of Jacques Casanova de Seingalt, Vol. 3 of 6: The Eternal Quest, we are introduced to our Venetian count as follows:

“In the beginning of March, 1757, I received a letter from my friend Madame Manzoni, which she sent to me by a young man of good appearance, with a frank and high-born air, whom I recognized as a Venetian by his accent. He was young Count Tiretta de Trevisa, recommended to my care by Madame Manzoni, who said that he would tell me his story, which I might be sure would be a true one.”

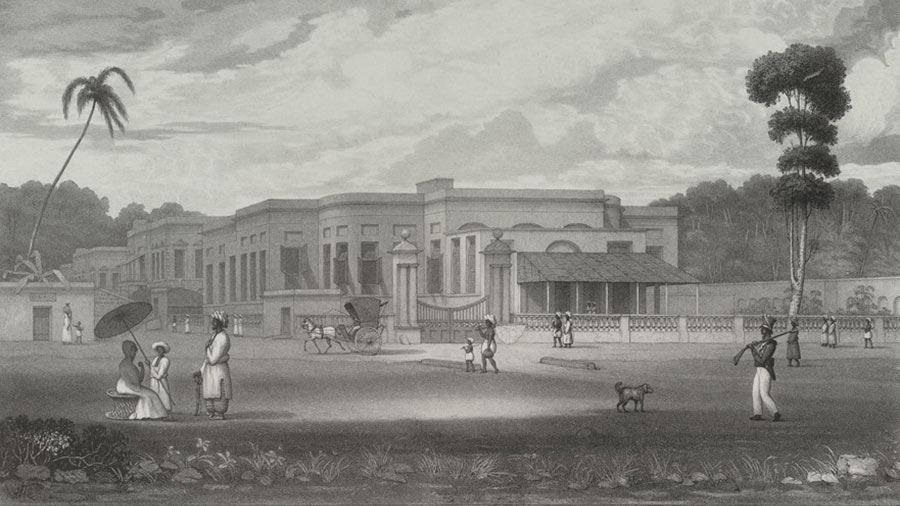

‘The Bengal Levee’, an etching of a levee by Lord Cornwallis is believed to have Edward Tiretta in the frame as the man talking to a Greek priest dressed in black (left, at the back) British Library

Over the next few years, Tiretta would become a close friend and confidant of Casanova, and by all accounts, his activities were right down Casanova’s alley.

This is illustrated in French historian and author Chantal Thomas’s book Casanova, Un voyage libertin. In the chapter ‘Casanova and the Revolution’ (‘Casanova et la révolution’) she writes, “... he (Casanova) watches his friend Tiretta kissing La Lambertini: “Being very close behind her, he had tucked up her dress so as not to step on it which was as it should be.”

To come back to Tiretta in Kolkata, sometime in the early 1770s, Tiretta lost his mistress and wanted to try out new environments. Casanova gave him a letter of recommendation and sent him to a respectable gentleman of the Dutch East India Company in Amsterdam who got him a clerical job in Batavia (roughly corresponding to today’s Jakarta). However, Tiretta got involved in a scandal soon and had to make himself scarce. Thus, the count landed up in Calcutta. Here, his first name, Eduardo, was anglicised to Edward, the name by which he is commonly referred to and documented.

Tiretta Bazaar was set up by Edward Tiretta in 1783 TT Archives

Tiretta was clearly a man of some ability, or maybe, his long years with Casanova prepared him well to navigate the high society of late 18th-century Calcutta. He would, in time, become a civil architect and surveyor of roads in what was fast becoming the second most important city in the British Empire. Sometime around 1783, Tiretta received permission from the (British) East India Company to acquire land and construct a bazaar or market. Spread over nearly 10 bighas in today’s central Kolkata, this market was privately owned — something of a rarity at the time when most such structures were owned by the Company. It also carried its owner’s name, and was called Tiretta Bazaar. Tiretta also had a parallel and flourishing career in property speculation and lottery trade which earned him a good fortune.

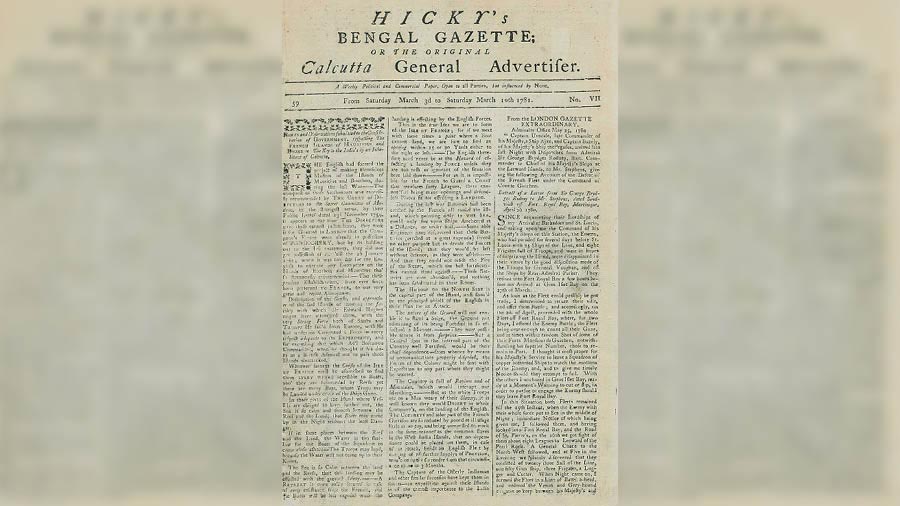

Edward Tiretta also had an intriguing encounter with James Augustus Hickey, the founder of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, often believed to be the first English-language newspaper of the subcontinent. As per contemporary accounts, Tiretta had a fetish for outlandish clothes and was also an incessant talker with a tendency to barge into conversations. In fact, once at the height of the sweltering summer in Calcutta, Tiretta arrived at a party in a suit made of rich velvet. Hickey dubbed him ‘Nosey Jargon’, an oblique reference to his habit of putting his nose in unconnected affairs and it was a sobriquet that stuck.

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette is believed to be one of the Indian subcontinent’s first English-language newspapers Wikimedia Commons

Despite the odd moniker and other things, Tiretta made good of life in Calcutta. By 1788, his bazaar was valued at two lakh rupiah.

Good times, however, often don’t last long. In about three years from that time, Tiretta had lost much of his fortune and was on the verge of bankruptcy. He was forced to sell off large parts of his land holdings, including his bazaar, in a lottery. A gentleman by the name Charles Watson won the lottery for Tiretta’s market but opted to retain the old name.

In his advanced years, Tiretta finally entered into wedlock with the orphan daughter of a French officer, the Count de Carrion. His wife was much younger and was expected to outlive him. Sadly, in those days, life in the Orient was quite unpredictable and in 1796, his young wife fell sick and died. Tiretta was heartbroken. He buried his wife at the Roman Catholic cemetery at Baithakkhana near Sealdah. However, he soon came to know that graves in the cemetery were often dug up for new burials and Tiretta did not want his departed beloved to suffer this fate.

Some of the graves from Tiretta’s cemetery were moved to South Park Street Cemetery (in picture) Wikimedia Commons

He acquired a plot of land on Burial Ground Road (the part of today’s Park Street leading to South Park Street Cemetery) and constructed a private cemetery there. His wife’s mortal remains were dug up and shifted to Tiretta’s cemetery and he gifted the cemetery to the Roman Catholics. A year later, the second person to be laid to rest there was coincidentally another Venetian, Mark Mutty. Over time, many Frenchmen were buried there, but sadly, no trace of Tiretta’s cemetery has survived today. Some believe that the cemetery stood where Apeejay School is located today on Park Street.

Chinese breakfast at Tiretta Bazaar My Kolkata

Just like his cemetery, the end of Tiretta’s life is also shrouded in ambiguity. It is generally believed that the Venetian died of old age in Calcutta and had the honour of being buried in his own cemetery. While his grave and the story of the end of his life might be lost, one part of Tiretta’s time in Calcutta lives on eternally in the city — his bazaar. The market still bears his name, although it has found a different iteration — Tiretti Bazaar — over time and remains a major landmark in the heart of the city. One of the city’s most historically diverse neighbourhoods near Lalbazar, the area is famous for its Chinese breakfast, among other things. Tiretta Bazaar reminds us today of this most colourful man, who made a home thousands of miles away from his birthplace.