India’s struggle for freedom has been the country’s most defining phase. The hubs where much of the revolutionary attrition played out were Bengal and Punjab. Bengal represented the markaz of this struggle; of all prisoners in India’s most isolationist correctional home — the Cellular Jail in Andaman — two of every three were from Bengal.

One would have expected that such a decisive contribution towards a defining movement would have been archived in built form in Kolkata. In any other country, a befitting institution would have been commissioned before a generation passed and voices stilled. For instance, within eight years of the Second World War, Israel’s Knesset created the iconic Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre, across 45 acres. Ironically, Kolkata — with possibly the highest number of inquilabis per sq metre than any other part of the country — had to wait 77 years for such a monument to become a reality when The Alipore Museum was unlocked in 2023.

Der aaye durust aaye (better late than never). I will also say this: the handicap of a considerably delayed regard for a rich multi-decade legacy has been more than made up by this museum’s built environment.

The Alipore Central Jail museum has taken the stories of our forefathers from books to bricks and rekindled the revolutionary spirit

It is not just good; it is outstanding. It is not just stately; it is infrastructurally befitting. It is not just presentable; it is pride-enhancing. It is not just a museum; it is a shrine. If you go merely to see what is inside, I suggest that you cast off your footwear and walk barefoot. If you go merely to see, I suggest you venture to the gallows and matha teko (touch your forehead to the floor). If you go as just a usual visitor, I suggest you read up on the trials of all those imprisoned. If you go as a citizen seeking to plug entertainment hours, carry some gratitude that it is because of those who perished inside that you can exercise this freedom.

The Alipore Central Jail (ACJ) museum has not come a day too soon. It has transposed the stories of our aaba-ajdaad (forefathers) from books to bricks; it has rekindled the inquilaabi jazba (revolutionary spirit) that could have dissolved in the rozmarra or the everyday of cynicism; it has deepened an understanding of what it means for a mind to be without fear and the head held high, a privilege denied to our ancestors. It has — at a more mundane level — created a landmark that should attract tourists to soak our city’s contribution to the world.

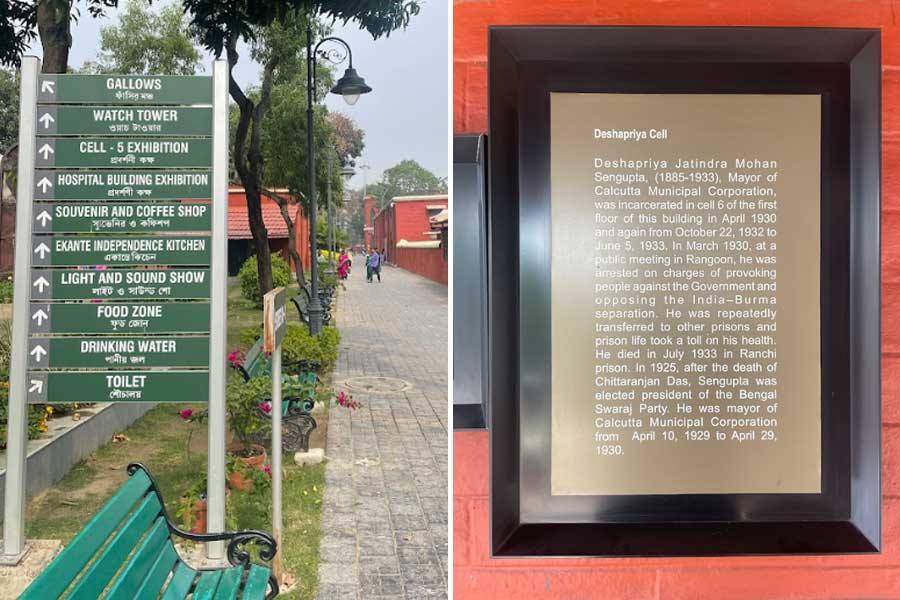

What I found pleasantly inviting at the ACJ was a sense of order. What has been curated by the Bengal government (more specifically HIDCO along with heritage architect Partha Ranjan Das) is world-class. I could not locate on-site tackiness; no blue and white; no signage misspellings; no ‘Monday first hour aashben’. On the contrary, I chanced upon disciplined colour coordination; I saw manicured presentability. I found myself saying to no one in particular, ‘This could have been anywhere in the developed world.’

All the things to appreciate at The Alipore Museum

The colour coded signage, and the factoid boards are among the things to appreciate at the museum

One, the presentability of the staff. I did not find anyone in home clothes, chappals, buttons opened or betel-chewing; no inattentive security guards on cell phones. This sent out a positive signal from the time I bought my ticket.

Two, the general hygiene of the place, which includes no plastic litter, no overflowing bins, no flags on the premises announcing trade union political affiliations, no graffiti, no uneven grass and no brown patches in garden areas.

Three, the citizen-friendly signage, the colour coding, the factoid boards, the standardised framing, the frame mounting and the distinctive typefacing (it is amazing how much can be gleaned about a premises from this detail).

One of the best rooms in the museum is the one showcasing the story of Bengal’s women freedom fighters

Four, the coffee house, food court and a baby feeding room on the premises — acknowledgements of the fact that people being people will have diverse needs and as opposed to the usual ‘Eikhaane to oi-shob possible noi’ (this is not possible here). Someone actually curated this into the museum design. The unspoken message that the curators transmitted was that ‘We want you to come, relax, enrich — and come again.’

Five, I walked longer in the room that archived the story of Bengal’s women freedom fighters. The prudent use of visual illustrations (often flippantly referred to as comics) is likely to appeal to audiences overdosed on text; the use of life-size statues of Sri Aurobindo, Subhash Bose, Chittaranjan Das and Kazi Nazrul — it looked as if he would abruptly rise and shake my hand — enhanced a lived-in feel.

The use of life-size statues enhances the experience of knowing the stories of Bengal’s revolutionaries

Six, the combination of the amphitheatre, seminar room and the technology rooms where it is possible to narrate, discuss and visually simulate the stories of our freedom fighters – extending ‘something I read’ to ‘something I saw’. There is an attempt to graduate ACJ onto the lecture circuit through the prudent utilisation of its modern lecture room. I find this refreshing.

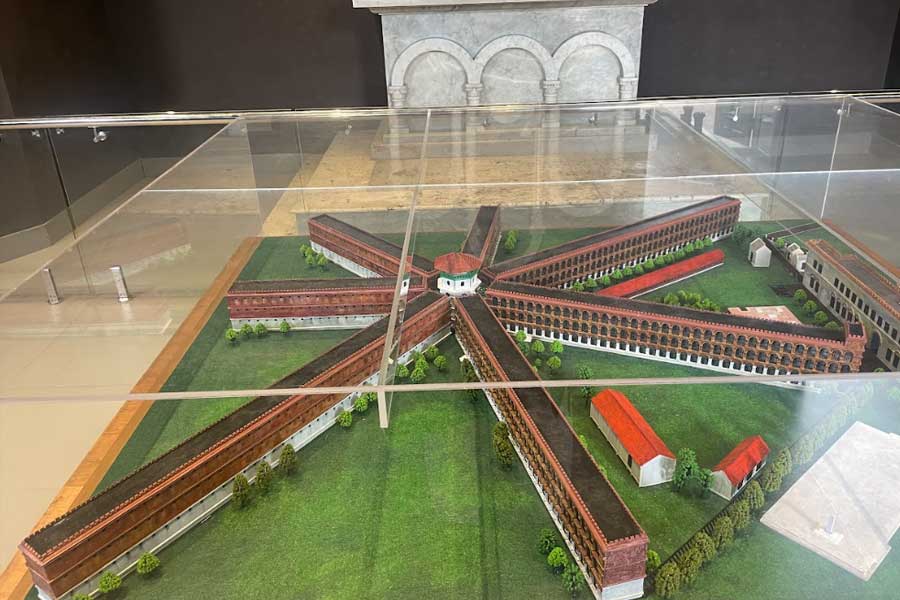

Seven, the panopticon spread of the radial premises that was captured in a mini-model in one of the rooms indicated just why this jail had no shadow zones that made it increasingly difficult to escape.

What I did not like

The toilets. I judge the integrity of a location and management pedigree by the toilet hygiene. A number of people may insist that this is almost impossible to achieve in a country with a varied audience profile. I disagree. What toilets need in a public place like the ACJ is an airport-like ongoing cleaning activity as opposed to a cleaner materialising with a mop at the end of the day and ticking a box.

The mini model which recreates the panopticon spread of the radial premises of Alipore Central Jail

The guides. I did not find a single one on the premises. Without guides, the ACJ will be largely brick and mortar for most. If young multi-lingual history interns from prominent colleges weave stories of lives in these prisons — the European rank and file inmates would be ‘encouraged’ to assault Indian political prisoners or how the absence of lights after 6pm in these jails sharpened the hearing of prisoners to the point that they could identify individuals by their footsteps — then there would be an audience willing to pay top rupee for the narrative. I dream of a day when these informed guides earn a good living, widening the tribe of Kolkata storytellers.

The research. What one saw in the jail was limited and indicative; the larger part of the story remains to be researched, archived and communicated. There is a wealth of Freedom-centric material lying disaggregated; this would need a dedicated wing of full-time researchers to bring into active narrative.

The amphitheatre, seminar room and the technology rooms attempt to graduate ACJ onto the lecture circuit, though the blue-and-white lighting is off putting

The book centre. The museum lost an opportunity to create a comprehensive book centre on the premises dedicated to India’s freedom struggle, stocking biographies of freedom fighters and the histories of revolutionaries. If competently curated, this could become the most authoritative book corner on the subject in the country, feeding off and into the museum walk.

The photo ambush. I appreciate the vision of the Bengal government in relocating the erstwhile correctional home to Baruipur, and turning this facility over for adaptive reuse by a competent HIDCO. Full credit. However, there is evidence that the government might have swung the pendulum to the extreme by reserving an entire room to showcase all its awards and achievements (who cares?), including framed pictures of the lady who must not be named with Juhi Chawla and Shah Rukh Khan (what the hell). When I saw the Biswa Bangla store on the premises, I refused to enter on principle. The ACJ must remain an apolitical ‘island’; I see the political ambush as a slur to the memory of the Boses, Khudirams and Aurobindos.

The Biswa Bangla store on the premises

The lights. The ACJ is illuminated in blue and white tuni lights, the kind used in semi-urban shaadi baris and para onushthaans. Another insult to the memory of the incarcerated if the first recall in my mind is that of ‘Pintu weds Pinky’.

There is something that transpired the other day in a different context that I should end this piece with. In my role as a heritage facade illuminator, I chanced upon Holy Trinity Church on Amherst Street. I would have left after seeking permission from Reverend Saikat Nath for illuminating the spire of this church at a cost to be funded by an anonymous group called The Kolkata Restorers.

While walking out, I chanced upon a reference to Reverend James Long, an Anglo-Irish priest of the Anglican church in 19th-century Calcutta, who had presided over the adjoining school, college and church. Reverend Long had studied the exploitation of the indigo farmers; he published the English translation of the play Nil Darpan by Dinabandhu Gupta and for this act of defiance against the prevailing Angrez hukoomat, he was prosecuted, fined and jailed.

There was something else I noticed when I walked out — a hole in the spire of the church. Reverend Nath indicated that decades ago a two-faced clock had indeed existed; the disused equipment was discarded. I asked if a part of the equipment still existed; he said yes.

Na samjhoge to mit jaaoge ai Hindustan waalo. Tumhaari dastan tak bhi na hogi dastaanon mein

— A ‘kalaam’ by the poet-philosopher Iqbal

The long and the short of it is that The Kolkata Restorers have embarked on the restoration of the clock and a couple of months down the road, the Holy Trinity Church will resound hourly to the strike of the gong. I have a sneaking feeling that the memory of my visit to the Alipore Central Jail with its subconscious whisper ignited a floating sentiment that ‘We must save what we still possess.’ There is a kalaam by the poet-philosopher Iqbal: ‘Na samjhoge to mit jaaoge ae Hindustan waalo. Tumhaari dastan tak bhi na hogi dastaanon mein.’ (Without an understanding [of your past] you will slip into oblivion, people of Hindustan. Your tale will not even appear in the story of the world)

And that is why a pilgrimage to the baitul muqaddas (sacred place) of the ACJ is not just being suggested as a means of discovering some people you barely knew; it is about discovering yourself.