What was the signature landmark structure of Calcutta before the Victoria Memorial and the Howrah bridge came into existence?

The answer is a huge cathedral with a sharply pointed spire, which used to rule the skyline of Calcutta across the green carpet of the Maidan. It is, of course, St Paul’s Cathedral — one of the biggest and oldest churches of India, which still stands majestically with its splendid Indo-Gothic architecture.

With it’s political position cemented in India from 1757, the British East India Company and members of the European community of Calcutta were using Mission Church and St John’s Church for all its religious and social events, but thanks to the growing population from the early years of the 19th century, the need for a bigger cathedral was palpable. By that time, the city had grown as a cosmopolitan urban settlement and one of the prime commercial hubs of eastern Asia, overtaking even Hong Kong.

Proposal rejected originally

Thus, a proposal to build a massive cathedral was placed before Warren Hastings in 1819 by military architect William Nairn Forbes, but that was rejected by company officials for its huge cost.

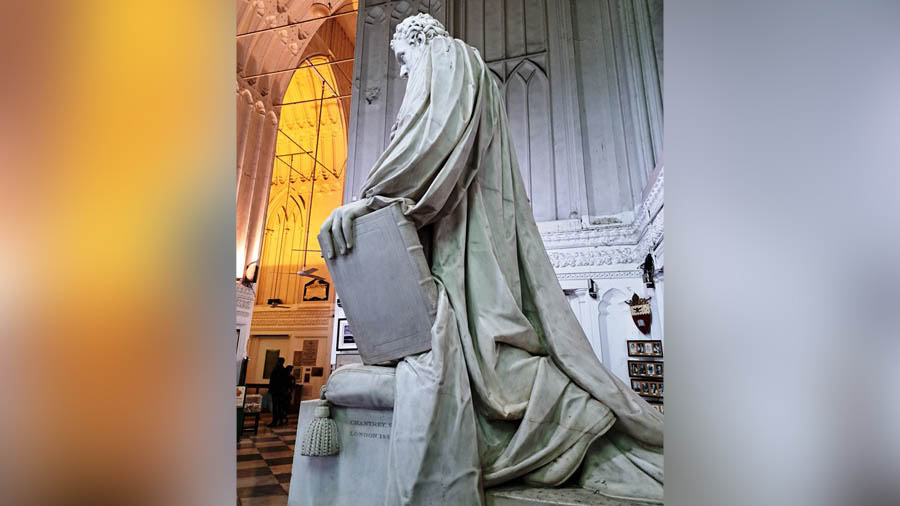

Meanwhile, Rev Reginald Heber came to Calcutta as a bishop, but died four years later in 1826 in Madras. As a token of respect, a plan to install his statue at London’s St Paul’s Cathedral and also in Madras and Calcutta was initiated. The statue finally arrived in Calcutta in 1838 and was temporarily placed in St John’s Church, though it was in need of a permanent home.

The statue of Rev Reginald Heber Somen Sengupta

This need created the demand for a building, in the form of a new cathedral. This time, the bishop of Calcutta, Daniel Wilson, was able to get sanction of a land in 1832 and an architectural design was executed by William Nairn Forbes and C.K. Robinson, two noted military engineers. The design of the new church was done in a revivalist Indo-Gothic style, with a long running nave and a sharp, pointed spire. It was heavily influenced by Norwich Cathedral of London.

Original measurements

The foundation stone of the new cathedral was placed October 8, 1839, and it took eight long years to complete. Finally, on October 8, 1847, the consecration ceremony was performed and it was open to the public. It became the official cathedral of the company. Earlier, St John’s used to play that role. It was inaugurated as the first episcopal church of the east and Queen Victoria sent a Communion Plate to Bishop Wilson for its inauguration ceremony.

Originally, the church was 201 feet tall at the spire, but an earthquake in 1897, and another one in 1934, reduced it to 145 feet. It is 247-feet long and nearly 81-feet wide. The spire, which was damaged in 1934, was replaced by a new attractive design influenced by the bell tower of Canterbury Cathedral. The new revised tower was given several giant clocks.

The tower was renovated after being damaged by an earthquake in 1934 Somen Sengupta

The giant statue of Heber is now on the right side of the entrance. The statue, which is considered one of the finest surviving colonial artworks in Calcutta, was sculpted by Francis Leggatt Chantrey in 1835. There is a huge marble baptismal font in front of the statue.

The main attraction of the church is its grand prayer hall. The nave is wide and decorated with a series of wooden pews that can accommodate more than 1,000 people. The nave ends at the altar, where six candles and a cross are placed. The altar, on its left, has the seat of the bishop, while on the right, it has seats for bishops from other states.

The nave, pew and altar Somen Sengupta

The reredos is decorated with outstanding woodwork and colorful stained glass. There are five arches and the central one is the biggest of them. The stained glasses show various apostles of Christianity and also some events from the life of Jesus. The church has painted stained glass installed on every single arched window, and the biggest is the one opposite the altar. This makes the church interior look elegant and bright, making it comparable to any first-grade church in Europe.

The memorial chapel Somen Sengupta

The cross of the church is called a ‘Coventory Cross of Nails’. Artworks of Subir Kumar Bairagi can be seen on the wall. It is also embellished with memorial plaques of Rev Daniel, the fifth bishop of the church and its chief architect William Nairn Forbes. The northwest entrance of the church is dedicated to Sir William Prentice, who was pastor of the church for 30 years.

Bang opposite of Heber’s statue lies a small memorial chapel, where an exceptionally surprising item of this church is placed at one corner. There is one big cross made of a charred wooden beam that tells a jaw-falling story, which can be read here.

The charred cross of Bangladesh Somen Sengupta

The walls of St Paul’s is nothing but a gold mine for history buffs. They have a plethora of marble and metal dedicatory tablets that in short give us a trip through India’s colonial history. From personal memorials to memories mingled with the Great Mutiny of 1857 and WWI, to various iconic events, the tablets are a delight for any student of history.

A close read of these tablets reveal that almost all major wars fought by the East India Company, and later by the British India government, have a reference on these — be it the Siege of Multan or the Afghan War. The stone tablets also remind visitors that the first pastor of the church was Henry S. Fisher. At the time of Independence, the pastor was Gilbert B. Elliot. The first Indian pastor was Kenneth D. Anad — from 1957 to 1959.

Memorials inside the church Somen Sengupta

The church was visited by Queen Elizabeth on February 19, 1962. Memories of that event are framed on the wall. Many premier educational institutes of the city, like Scottish Church College, St Thomas Day School and St Paul’s schools, come under this church.

Under its roof, the cathedral contains a plethora of history in its dedicatory tablets, memorials, statues, artifacts, paintings and priceless documents — revealing many unknown or little-known chapters of our heritage. In a nutshell a visit to St Paul’s Cathedral is extraordinarily meaningful, if properly curated.