The Ahilya Fort Hotel at Maheshwar in Madhya Pradesh is not for the faint-hearted. You reach Maheshwar town via Indore, by train or plane, then board a car that carries you through the heart of India with its wheat and maize fields and tiny tinkling temples. You cross into the centre of Maheshwar town and wind up a narrow lane going up to the fort, a muddle of sari, utensil and jewellery shops on either side, till a boom barrier separates the more public areas of the fort from the boutique hotel that lies behind the black wooden doors.

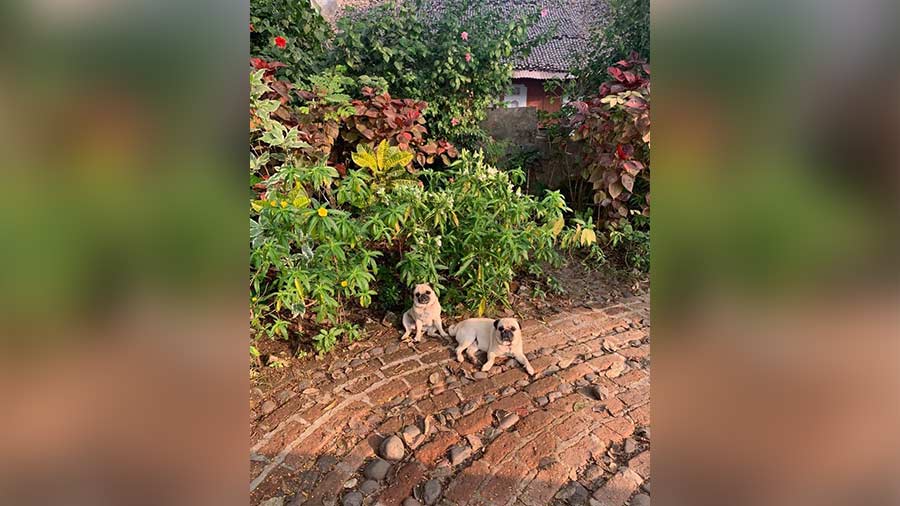

You climb up steps that are really blocks of stone — hewn hill, now fringed by asters and chrysanthemums, the royal pugs greet you with a sharp volley of woofs, you are welcomed with garlands by the graceful Aimee Junker (guest relations) and Kunta Bai of housekeeping (the resident Mrs Danvers in a sari and bindi) and suddenly you are standing three hundred feet above the River Narmada in a quadrangle shaded by neem trees, signing the guest register on a period table.

The royal pugs Monabi Mitra

Above is a framed portrait of Yeshwant Rao Holkar II, the last Maharaja of Indore and father of Prince Shivaji Rao, better known as Richard Holkar, the present owner and host of this hidden gem. You catch your breath and close your eyes and 2023 seems far away. Here, under the shade of a towering neem tree tumbled over by a climbing Flaming Glory, parakeets screech, a robin whistles and there sits a langur, soaking in the sun and watching quietly from the stone-tiled roof.

For those who want the ugly paraphernalia of gyms, business centres, strong wi-fi, 24-hour room service and an array of exotic massages, stop reading at once. For others (a dwindling number, alas) who are willing to dine alfresco on gourmet cold soups, light salads, home-made banana upside-down cake and Glenburn tea, who are willing to clump up and down stone steps and winding verdurous ways for breakfast and dinner, heralded always by a short burst of drum beats as a stand in for a dinner gong, who can stare down for hours at the great river flowing beneath, teeming with life, strains of temple bell and devotional songs floating up — the Ahilya Fort Hotel is the place to be.

The reception area of the hotel Monabi Mitra

Ahilya Fort was built by Queen Ahilya, better known as Ahilyabai, in the 18th century. Ruling from 1767 to 1795, her reign was a time of peace in the Holkar territory, while beyond its walls Indian history was seething with a power change. The Mughals were on the wane and the new colonial powers, especially the British, were pushing through. Ahilyabai herself led a saintly and devout life, becoming queen at the age of 30, after the demise of her husband and son, choosing to be close to the river and the holy shrine of the Omkareshwar Temple. The fort was built as a defence establishment, but the rani made it more in the style of a private home. Just beyond one of the dining areas is the queen’s prayer room, filled with scores of stone lingams fashioned from the stones of the Narmada. At the entrance to the palace stands a palanquin and visitors stream in to stare at the areas where Ahilyabai held court. To its left is the temple complex containing the chatris or cenotaphs, including the Vithoji Chatri and the Ahilyeshwar Chatri, both restored during the filming of Mira Nair’s Netflix series A Suitable Boy, many of whose scenes are shot here.

Many scenes of the Netflix series ‘A Suitable Boy’ were shot in Ahilya Fort Netflix

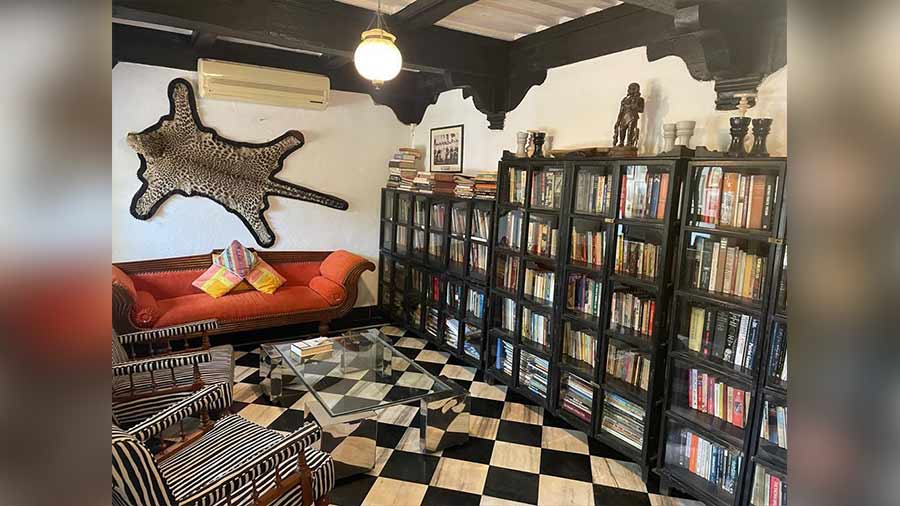

The hotel itself is a maze of courtyards and quadrangles, the rooms are bundled according to their location with evocative names such as Badam Chowk, Naqarra Wada, Lingacharan, Poshak Wada. There is a flowing Wonderland feel about each part of the hotel. The central quadrangle or Poshak Wada houses the reception area, as well as a long room housing the library. Inside the library is a chaise-lounge and two wicker chairs, a leopard skin is nailed on the east wall (we are in a Maharaja’s home after all) but the other walls have bookcases lined with the homeliest of books — Ford Madox Ford, Wodehouse, A.S. Byatt, Shaw. A television set has been placed discreetly in an anteroom, a concession to the travails of modern living but it stood disconsolate and silent and I didn’t see anyone turning it on.

The library Monabi Mitra

Exit library and take a walk! Turn a corner of a cobbled path and find a courtyard where water tinkles down into a stone urn; take another turn and you chance upon the swimming pool in a small grove of bamboo and banana, go further down and you are in the vegetable garden with rows of cabbage and turnips, climb up a steep stone staircase and you are suddenly on the top of the fort, flag fluttering before you, turrets and battlements around you and far, far below the Narmada curving away. So must it have looked to the sentries on guard at the top 200 years ago, scanning the shimmering horizon for a bit of enemy sail or mast!

View from the terrace of the Ahilya Fort Hotel Monabi Mitra

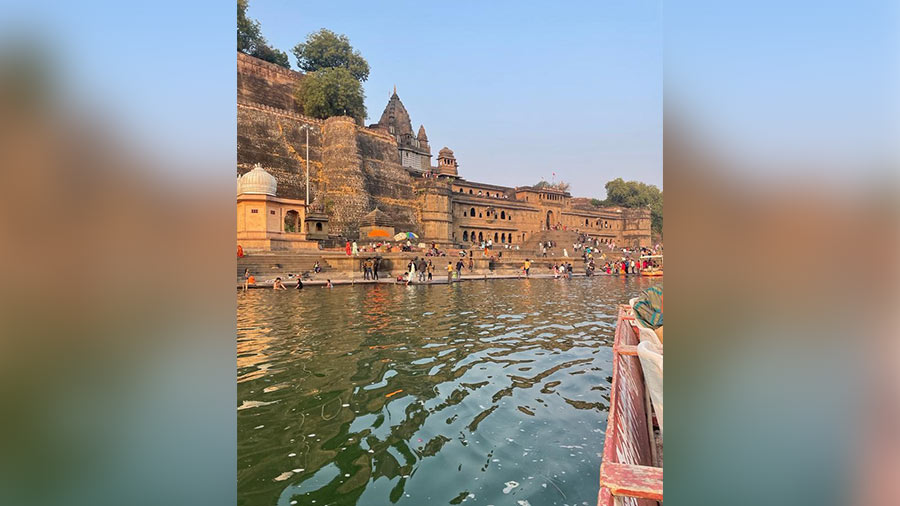

On the eastern ramp of the entrance quad is a black door, low and wooden, leading outwards onto a cobbled path. Here, the hotel merges into the shallow stone steps that lead down to the ghat. Here is a microcosm of Maheshwar, out to enjoy a winter sun on a weekend. A sadhu sings in a cracked voice keeping time with a chimta, a pair of tongs. A ragged boy sells pellets of mashed flour to feed the fish, a family buys three platefuls and watches happily as carp and snakehead fish snatch the pellets greedily in great loops of bubbling water whorls. Three women take a dip in the holy water, muttering incantations. A family have spread out a picnic of namkeen and samosas on the pier as they watch the boats chug in and out with tourists. Lovers sit on the ghat steps, taking selfies. Vendors with cameras slung around their shoulders take photographs of larger groups. Stately looking goats with long, sleek dachshund-like ears sniff out chickpea curry from abandoned paper plates. Three cows snag a sprig of coriander from a man selling snacks. A woman enters a Shiva temple with flowers and proceeds to bedeck the lingam with flowers.

Tourists and locals on the ghat steps Shutterstock

We wait for a boat to take us out to the Baneswar Temple on a tiny island in the middle of the river, built in the 15th century. Our boatman deposits two cane hampers with tea and biscuits on the ghat as he poles his boat in. He uses a combination of hand hauling, rowing and punting to take us to the middle of the river and I am glad, for this must have been the way Ahilyabai was rowed to the temple. I imagine her, sitting in her barge, listening to the gentle slopping sound as oar hits the water, perhaps it is an orange dawn, a casket of flowers beside her. Better this way than the monstrous hooting of the fuel driven motorboats that unfortunately, also roar up and down alongside us.

Baneswar Temple, locals say, sits on an axis that connects the centre of the earth to the north star Monabi Mitra

The Baneswar Temple, as locals tell us, sits on an axis that connects the centre of the earth to the north star. Dasarath the boatman stops the boat dexterously as passengers climb up the steps that rise out of the water to the shrine. I use the time to lean out over the boat and plunge my water bottle into the water to collect a little bit of Narmada to take home with me. Later on I cannot tell the difference between a bottle of Bisleri and a bottle of Narmada- the latter being crystal clear. As we pole away the sun has sunk low and suddenly dips over the horizon. A couple of egrets and herons sit on the temple top; a moorhen puts out an anxious face from a clump of reeds as we pull away. The walls of the fort glow red and orange in the twilight.

Ahilya Fort from the water Monabi Mitra

At night, we have Maheshwari iced tea on the terrace overlooking the river. The sky is brilliant with stars, Orion hangs low and Jupiter twinkles from between the branches of a mighty gulmohur that overhangs our table. We are wearing the stoles and scarves we have purchased from the Rehwa Society, the weaving community put together by Richard and Sally Holkar in the late seventies which saved the Maheshwari loom from potential oblivion. Maheshwar had always been a centre of handloom weaving from the fifth century, while Ahilyabai supported the craft by bringing in weavers from the South and creating the look of the modern ‘maheshwari’ textile. With the passing of time the handloom was dying out and it was only due to the Holkar patronage that it survived. Most of the fabrics used at the Ahilya Fort Hotel use the Maheshwari textile in one way or another.

A boat has anchored midstream. A long line of diyas, paper lights with a single wick is being set out from the boat. The line of floating lights is surprisingly steady, no teetering or drifting randomly away but a clean straight arrow of bobbing wicks. The stars twinkle down at this firm line of beautiful diyas drifting away down the river, a flock of white cranes fly across the sky and from afar we hear the sound of a bhajan, strains of songs of praise. Then the thrum of a dholak announces dinner and we wind our way down to the Poshak Wada. Another day at the Ahilya Fort Hotel has ended.

Monabi Mitra teaches English at Scottish Church College, Kolkata, writes crime fiction and is a heritage enthusiast. You can connect with her on her blog at www.monabimitra.blog.