It is only in the past couple of decades that I have realised that the most important photographer on earth is someone I have easy access to — my father. The more I go through old family albums, the more I find my mother slowly moving out of the frames to give my sister and I more room and the Alsatian that managed to escape all frames of life decades ago — Poppy. But that one man is missing in almost every photo — the entire stash of seven or eight boxes. After all, he is my greatest photographer, always standing tall, at times lying flat on the floor, pointing his Nikkormat all over the place. The story is the same in almost every family.

My father was immensely proud of his Nikkormat — it was almost a family member. Frankly, I can’t recall a moment of the now

71-year-old without his turntable, carrom board or camera. A couple of weeks ago, I found that same level of passion in Aditya Arya during a recent visit to Gurugram.

In an image-saturated world, Aditya has managed to achieve something priceless. He is the force powering Museo Camera, Centre for the Photographic Arts, the largest not-for-profit photography and camera museum in South-East Asia. But adjectives like largest, biggest, grandest don’t interest him. He is at his best with an audience of school students who want to know the importance of photography and cameras; people who want to know about the process of capturing memories. He feels great to be alive at a time when photography has been democratised to the point that we are all photographers, thanks to the smartphone in our pockets.

Museo Camera is an oasis of visual nourishment in the middle of business-savvy Gurugram.

The four pillars of photography

A few phone calls later, I reached Aditya’s den where he is always busy running around the 18,000sq ft Museo with a walkie-talkie in hand, continuously calling colleagues to keep things in order, or answer an endless stream of phone calls from the who’s who, enquiring about the collections that are being showcased or about workshops. The only time he is free is while staring at the collection. After a quick greeting, he whisks me away for a tour of his museum. It’s a beautifully planned-out space with perfect lighting.

He doesn’t give away his sadness (or perhaps anger) when asked about the first days of the museum, which was around five-and-a-half months before the first pandemic-induced lockdown was announced. What’s on his mind are possibilities with the space in the coming months and years. (The idea for Museo Camera started formulating in 2009 in Aditya’s basement as a personal collection of photographic equipment.)

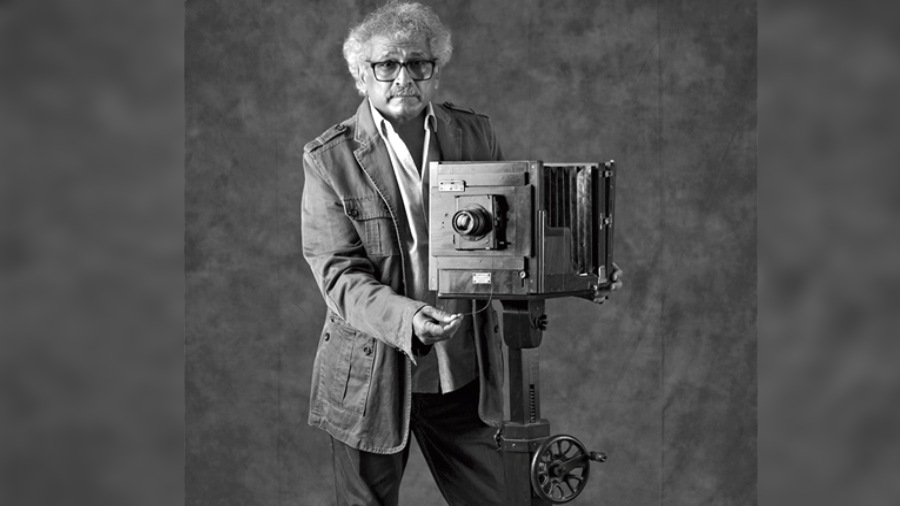

Aditya Arya is director, Museo Camera. Picture: Dinesh Khanna

Museums are places that ignite minds. Museums inspire. Somebody has defined museums as a cabinet of curiosity

Aditya Arya

The journey began with the room housing a pinhole camera. “Everyone knows the pinhole camera. It is the ultimate idea of a camera, which evolved from the pinhole,” he says with a lilt in his voice.

“It’s camera obscura. It is an ancient optical device, which comes from the Latin word ‘dark room’. So when the judge says the proceedings will be held in a dark room, he means in his room or his chamber. And camera comes from ‘kamara’ or what we call ‘kamra’, meaning room. In many languages you will find that camera and ‘kamara’ have a similarity,” says Aditya, who could well have had a career in the Mumbai film industry. After doing still photography for Kundan Shah’s legendary Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro, he thought films were not his, well, language.

The excitement is infectious and makes one forget all other appointments for the day. He quickly points out that in the 16th and 17th century, some of the most famous painters in the world, like Johannes Vermeer, actually used the device. They used to put a tracing paper over what was being seen through the pinhole camera and then trace it out before filling in the colours. “They had issues with perspectives and forms.”

“There are a lot of people analysing how people like Vermeer and other Realist painters came up with such perfect paintings. They used this device. Some of these famous painters who came to India, like (Thomas) Daniell, would do sketches and then take these and fill in the colours.”

It was also the age of alchemists and the golden age of discovery. “Inventors wondered: ‘Why can’t we have some kind of substance that will react to the light and make an image appear.’ That led to the discovery of photography.”

Soon we reach a part of the museum with pictures of the four people who matter in the world of photography. The first is Joseph Nicephore Niepce. “He created the world’s first image, which took him eight hours to register. He got an image. Subsequently, another Frenchman, Louis Daguerre, who was his contemporary and sometimes his business partner, created the Daguerreotype camera. He was the man who created the most perfect images and said ‘I have seized the light. I have captured its flight’. He went to the French government to get it patented.

“On August 19, 1839, the French government said it was too important a discovery and couldn’t be given to one man. They paid him off and made it a gift to mankind.”

But the word ‘photography’ wasn’t born yet. “We have an ad from that era and it read ‘Get your likeness done.’ You will not find the word photography. It is the third gentleman, John Frederick William Herschel, who said this is photography or in Greek: Writing with light. Then he pointed out to the world that there was a problem — the system doesn’t have a negative. And if you don’t have negativity you won’t have multiplicity. His colleague, William Henry Fox Talbot, established photography as a negative/positive process. So these are the four pillars of photography.”

The cabinet of curiosity

Aditya’s love for photography is entwined with his respect for history. “The purpose of this museum is that it traces the history of photography. It tells how technology has been evolving. What led to what,” he says while pointing to cameras and camera parts. Also a big part of the museum is the story of different camera brands. “Once the French removed the patent, Americans were there. So the French invented it, the Brits perfected it and the Americans marketed it. They made money,” he says.

Once at Museo, you are certain to spend at least two-three hours there. There are experts to help you understand everything about photography.

In fact, before my visit to Museo, I often wondered what kind of concoction people drank before posing for photographs. In 20th century photos, expressions were as tight as Mick Jagger’s leather pants. There’s a reason behind it, something I understood soon after Aditya started talking about the People of India project, which Lord Canning had commissioned. Eight volumes were dedicated to understanding the different castes and tribes of India.

“Why are these people not smiling? Why is it that in Victorian images people are not laughing or smiling? Because technology did not allow them to laugh. The exposure time was 15 seconds to half a minute to one-and-a-half minutes. So you had to stay absolutely still. It’s not that people didn’t want to smile but technology did not allow,” he says.

Aditya has dedicated around 40 years of his life to photography during which he also collected cameras and stories about photography. Almost everything seen at the museum is from his personal collection and an equally strong collection still resides at his home.

“I studied history in college (St Stephen’s College) and what interested me a lot is visiting important places to see different objects. They excited me more than reading that Babur went from here to there. I thought, can I go there and see how it is? These are stories that excited me; to connect the dots. History comes alive. So this is the history of photography and of my profession,” says the historian and archivist.

Very important to his sphere of interest is interacting with children. “Museums are places that ignite minds. This is how it happened? Why can’t I think of this? Museums inspire. Somebody has defined museums as a cabinet of curiosity,” says the 61-year-old photographer.

Museo is certainly igniting young minds. Take for example its ‘The Art of Storytelling’, a week-long mobile photography workshop in collaboration with the Murthy Nayak Foundation at village Churi Ajitgarh in Mandwa, Rajasthan. Twenty-two children from an underprivileged background were chosen and provided with iPhone 12 phones to create a photo series. The final results are simply joyous.

Democratisation of photography

Soon we were face to face with a section dedicated to how negatives are developed. “Today everybody thinks in terms of instant gratification. This used to take hours… to shoot and to learn. Analogue (35mm) gave you 36 exposures. Today, digital gives you endless possibilities. Back then you had to create an image here and you had to be perfect technically. Now you can create ‘n’ number of mistakes and fix it on Photoshop,” he says.

Quickly he points me to this collection of the K-20, which was used by Americans to document Nagasaki and Hiroshima. It was meant for aerial reconnaissance and documentation. “Where do you think American photographers were trained during the Second World War? Kharagpur. I have pictures of darkrooms there. Recently I got an archive of a British soldier from 1941. A few thousand negatives. He shot these photographs between 1941 and 1944 before he left India.”

As we kept talking and moving around the museum and the exhibition space that’s attached to it, calls continued to pour in. Obviously, what does he think of the camera in our pocket? “Everything will converge here and it will converge more and more. We conduct classes for village children, teaching them how to create stories through their phones. I have nothing against it. If you are a painter, there are many ways to express yourself. How you express yourself is all that matters,” he says with a smile.

The man had spoken. Let’s stop mocking people who like to document lives and their surroundings with a smartphone. It was also the perfect note on which Aditya took leave for an important meeting in Noida. I decided to stay on and take a look at the exhibits and I soon realised that even though the technology of taking photographs has undergone a change as complex as sand dunes, something remains unchanged. The idea behind photography was, is and will remain simple — telling it how it really is.

Everything will converge here (the smartphone) and it will converge more and more. We conduct classes for village children, teaching them how to create stories through their phones. I have nothing against it. If you are a painter, there are many ways to express yourself. How you express yourself is all that matters

Before electricity arrived, curtains were moved in different directions to get maximum light into a frame

Process camera, also known as copy or repro camera, was used for graphic art photography and plate making

Vageeswari was known as one of the best field and studio cameras in the world, manufactured in India by K. Karunakaran. The first camera was priced at Rs 250

The K-20, a hand-held manually operated aerial camera used during World War II. It was used for reconnaissance imaging and post-bombing documentation