The birds chiselled on the rock surface of Purulia’s famed Pakhi Pahar have captured the attention of travellers for some time now. Part of the region’s Ayodhya Hills, this is but a small section of the growing canvas of artist Chitta Dey’s work. My Kolkata spoke to the 65-year-old about his journey and his work.

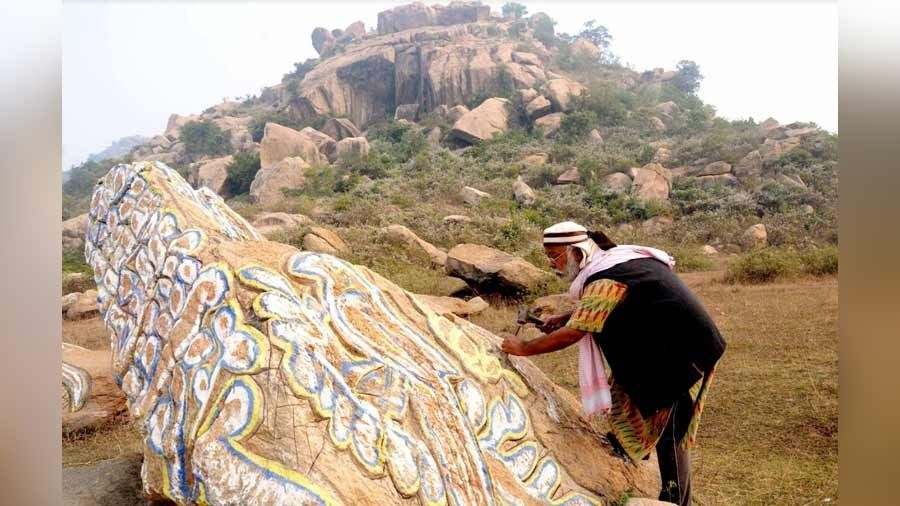

Winged masterpiece

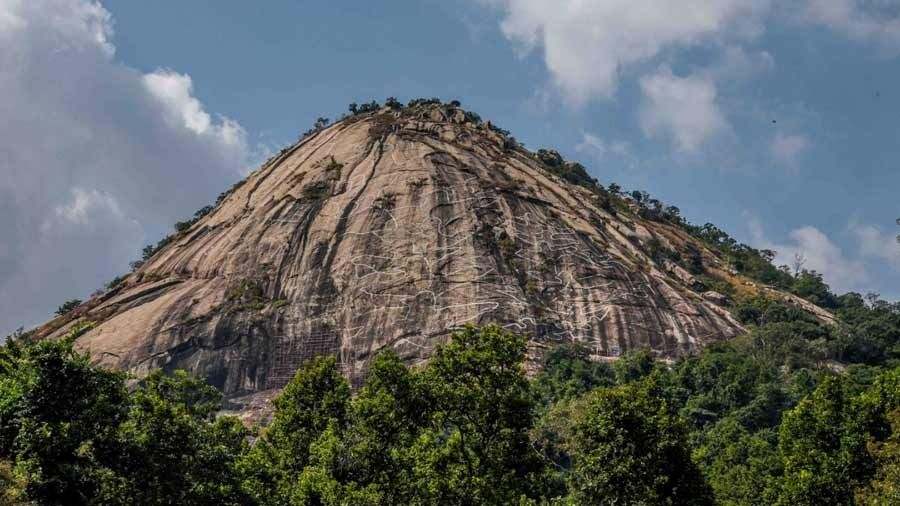

Pakhi Pahar, that carries Dey’s in-situ carvings of birds, is a well-known part of Purulia’s landscape Amit Datta

It was over three decades ago, in 1989, that Dey began to draw his Pakhi series. Birds, with their freedom to fly, always inspired awe in the artist. Growing up in Taki, he’d watch flocks take to the air after pecking on paddy fields, and the imagery has remained with him since.

Speaking about his inspiration, Dey recalled the last exhibition he participated in — in 1992. He created an artwork of a bird, which was too large to actually fit in the gallery space and he had to cut off parts from the wing to accommodate it. Later, on the request of the patron who bought his piece, he restored the wings of the bird to their original size. The experience planted the idea of wanting to give his art a bigger canvas. The sky was the limit and he wanted to showcase his work in a way that people could view without restriction — and the idea of Pakhi Pahar was born.

Humble beginnings

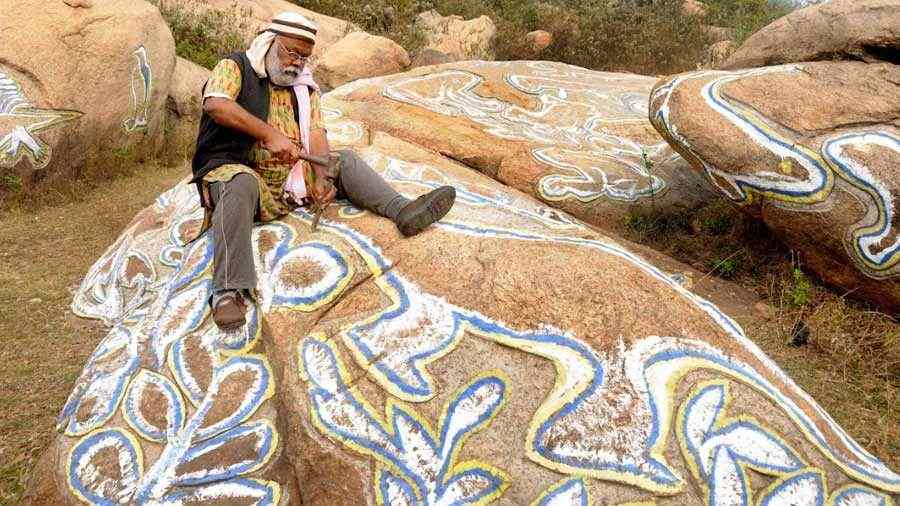

Dey believes that rocks inherently have images and once the extra bits are chipped off, the imagery is revealed Amit Datta

Born in 1957 to a lower middle-class family, Dey had an inclination towards the arts from a young age. His passion and interest in studying art at the Government Art College was not supported by his family. So, he left home and joined theatre artist Bibhash Chakraborty’s theatre group.

He took charge backstage for over a decade and also worked as a make-up artist for a long time after training under veteran make-up artist Shakti Sen. His work with Sen laid the foundations for his interest in sculpting.

It was an exhibition held at the Natya Mela in 1977, showcasing posters, photographs and set models of various theatre productions, which changed the course of Dey’s life. He created a set model of the play Chak Bhanga Madhu, which he fitted with fairy lights. The models on display were covered with a shade and thus only clearly visible when studied closely, making his lit-up creation stand out.

Along with Pakhi Pahar, Dey has also creating a series of carvings at nearby Kana Pahar Amit Datta

A decade later, in 1987, Chitta Dey became the art director of the first Bengali television serial aired on Kolkata Doordarshan, called Tero Parbon. Following this, he worked as the art director of other hit serials such as Sei Shomoy and Uranchandi. Offers for movies also came in, but Dey didn’t get much satisfaction. He had something larger than life in mind, and soon left his job designing sets to concentrate on painting.

Carving a niche

In the kilometre-long stretch at Kana Pahar, Dey has etched out artwork inspired by nature, including renditions of Triassic-era creatures Ashim Paul

Once the idea of Pakhi Pahar took off, and Dey decided to pursue the art of rock carving, he travelled to Barabar caves, Kalra caves, Ajanta-Ellora, Unakoti and many other sites to research.

The carvings of Pakhi Pahar and Dey’s other work in nearby Kana Pahar are in-situ rock carvings, which are a long-surviving subcontinental tradition. Unlike carved stone structures like the Konark Temple, where stone slabs are transported to a designated site and then carved, the in-situ carving involves creating sculptures where the rock is carved out in its own place.

Dey looks at his work at Pakhi Pahar as a means to protect the natural topography of the region from being destroyed or vandalised Amit Datta

At the heart of the concept of Pakhi Pahar are the ideas of peace, harmony and freedom. The project also focuses on preserving these naturally beautiful areas and the hills through art. Dey chose Purulia’s Ayodhya Hills as the site of his project after travelling across the country. He was given permission by then-Bengal chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharya and the project took flight.

Art in stone

The colours used to fill in the carvings at Kana Pahar are derived from naturally occurring sources at nearby Rang Pahar Ashim Paul

Dey’s more recent venture, that began in 2019-20 are the carvings on Kana Pahar, on Ayodhya Hills. In the kilometre-long stretch are colourful etchings of squirrels, elephants, frogs, 49 million-year-old Ambulocetus, or the Triassic Age Longisquama.

Five boulders in the area have been selected to carve out a cave and Dey plans to spread out his canvas with carvings on the hills of Charpaniya, Marble lake, Bamni and Shimatar, all along the Ayodhya Hills.

Rang Pahar in Purulia’s Mali village is locally called ‘malti khudan’ for the sources of natural colours found here Ashim Paul

An important part of this project is the Rang Pahar. The small hill in Purulia’s Mali village is a reservoir for natural dye sources. The colours on the region’s mud-wall houses usually come from here and the hill is popularly referred to as malti khudan (mine) by the locals.

Dey used the lime and stone derived colours from Rang Pahar to paint his own home.When the paint did not last long, he used a natural binder made from the leaves and stems of the panialata plant and mixed them with some chemical colours to create a stronger paint. It is this paint in shades of white, blue and yellow that colours his creations on Kana Pahar.

He is studying his creation and is hopeful that a chemical analysis will help him come up with a stronger natural binder.

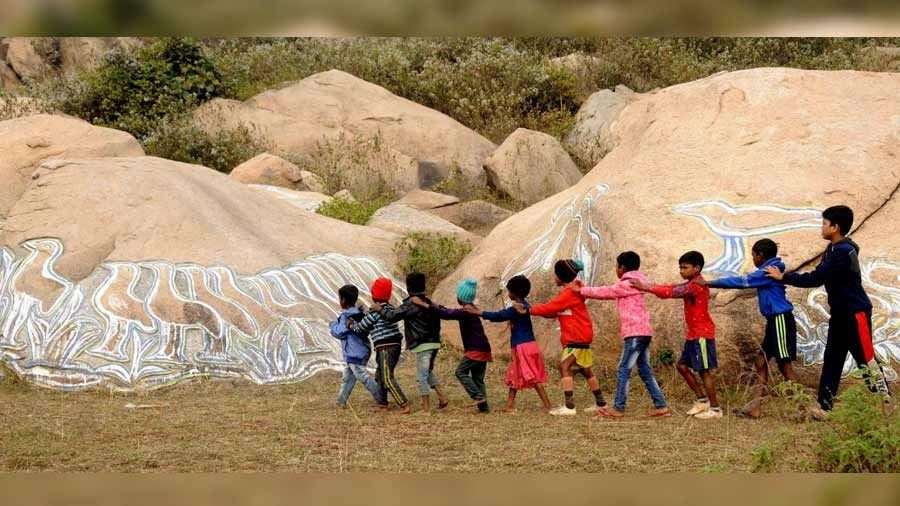

Dey wishes to pass on his skills to future generations, so they see his work not only as art, but also a means of conservation Ashim Paul

Passing on a tradition

Chitta Dey wishes to open a training centre in Purulia to pass on the skills he has learnt in the decades pursuing his art. He wants to appeal to the government to train the guides of Pakhi Pahar and to limit the movement of vehicles so these stone mountains can be preserved.

Dey hopes that future generations will see this work not only as art but also a step in conservation — protecting these natural mountains from desecration.

”I might not be able to finish the work of carving rocks, but the rocks that have been carved will be preserved,” he adds.