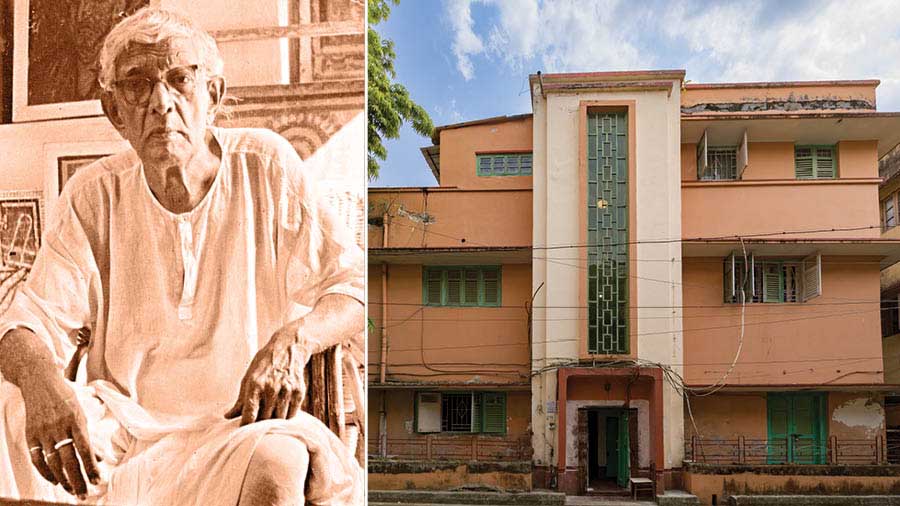

Three seemingly disparate minor events translated into one of the most extensive marine heritage restoration projects in Eastern India.

A few years ago, the chairman of the Kolkata Port Trust was taken on a conducted tour of the port’s premises. In the dry dock, he came across a parked red-brown paddle barge. He was advised, ‘Pandrah-bees saal se yahaan sarr raha hain, sir.’ The chairman interrupted his walk, calculated the notional national loss (sub-optimal space utilisation and lost cash flows). His cryptic diktat: ‘Buyer dhundho.’

Sometime later, on a trip to Bangladesh, he saw a paddle barge in action and ‘parked’ that memory.

And just when one would have thought that the coincidences would end, he was presented an invoice for the maintenance of the atrophying paddle barge in the Kidderpore dry dock. His signature was required before the accountants disbursed. ‘Isn’t this the same paddle barge that we had seen a few days ago?’ he asked.

The atrophying barge

These ‘events’, scattered across locations and weeks, kickstarted a sequence. A KoPT tender was issued to lease this ‘hopeless’ vessel. One of the only two firms that applied, advocated preservation over commercialisation (on the grounds of rarity value). The Port Trust liked that proposal and the firm was handed a multi-year lease to restore and operate. In an industry where water-unworthy vessels are methodically disassembled and sold, the vessel’s owner was telling the lessee the reverse: ‘Thou shalt protect and preserve.’

This explains how the Singhees – possessing decades of Port Trust familiarity – acquired the lease. They possibly (privately) regretted.

One, the vintage barge had not moved in 50 years, so the transaction was based on the optimism that when rusted metal cruised through alluvial water, the same tolerances would remain relevant. If they did not, then the vessel would slip off the platform or extensive water ingress would cause it to subside.

The barge at Kidderpore dry dock

Two, the vessel was ‘prepared’ for 40 days by a team of more than 50 so that it could be nudged out of the dry dock (‘chalne layak’) and be hauled two-and-a-half nautical miles en route to a marine hospital bed to be dissected. The engineers on the tug boat heard a series of cracks during two hours of cautious sailing time (‘That sounds like a break in the crankshaft’ and ‘That was loud, must be machinery giving way inside the engine’). Someone added: “Gayaa.”

Three, there were no blueprints to decode the vessel’s design. This was like a surgeon saying, ‘Let me open her up, study her, understand her and then decade what I would like to do.’ The decision to lease was made on looks and without looking within. Almost like an actuary writing out a health insurance on the basis of how the customer looks.

There were no blueprints to decode the vessel’s design

Four, the Singhees had been shipbuilders and marine service providers, focusing on the buyout and assembly of built components. What they now had sitting on their books warranted systemic re-engineering instead (replacement of the legacy coal-based system, for instance) and then components re-engineering, both competencies that were then beyond the company’s knowledge bandwidth.

Five, the more the restoration team ‘opened’, the more unusables it encountered. There were problems inside problems inside problems. The result is that a 200-tonne vessel gradually became a 450-tonne restoration challenge. A team comment that became active currency was “Jitna kholo utna loha kheenchta hain.”

Six, the project was driven with corporate savings pulled out of a predictably profitable business for onward allocation to a hazy capital allocation opportunity, so every rupee ploughed into the restoration (often interchanged with that dangerous word ‘dream’) could be – and probably was – interpreted as wealth destruction. The Singhees stopped tracking budgets after a point; if they didn’t know the transforming numbers, then they could not be intimidated into immobility.

The restored engine room

Seven, the challenge warranted multi-disciplinary competencies, which delayed the speed with which decisions needed to be taken. This, in turn, affected the return on employed capital, which, tested the promoter’s resolve.

Then, the pandemic. The vessel was being restored around the optimism that when complete, it would be a suitable place for personal banquets and corporate events. When the pandemic forced users indoors, there was an ambiguity over whether at all the world would re-congregate (however far-fetched this perspective may now appear), in which case every invested rupee would have to be written off the family balance sheet.

The pandemic put another spanner in the works

The Singhees pitched in for four battles.

One, the test of their consensual family decision making. Members held divergent opinions on restoration scope and scale now that the pandemic presented a multi-month implementation delay. Opinions ranged from ‘Can we go back to the KoPT and ask for a force majeure clause and exit the arrangement?’ to ‘Now that we have given our word, we may delay, but not dismiss, and so will treat this project like we have treated every customer – without compromise.’ Family juniors questioned elders. Debates attracted dissent. However, of the family stayed with the project it was because of ‘family values’. They held on. The emerging consensus stumped the accountants: ‘It is the only paddle barge of its kind in India. If this project and vessel are scrapped for metal value – Rs 30 per kg – it will be a step backward for national marine heritage. We will play this game for pride.’

The controls of the barge

Two, the battle of project commencement. Following the first couple of pandemic months, the Singhees recognised that every day of inactivity would enhance project cost and defer commercialisation. It launched a counter-offensive instead: it constructed portacabins inside its shipbuilding premises; 60 team members volunteered for on-site work away from their respective families; this team worked fortnightly shifts interrupted by brief leaves and pandemic testing.

Three, the extent of restoration. During the pandemic huddle, the Singhees could well have gone ‘kaam-chalao’ on the restoration extent, balancing the interests of the balance sheet, KoPT and paying customer (through a lower project cost and hence lower rental). The Singhees took a contrarian call; they said, “Let us do our best because such an opportunity may never recur.” The result is that family members accessed all available paddle barge reading material; some focused on examining hundreds of vessel items for onward recasting; some leashed costs and outgos. By the time the vessel was river-ready, an indicative 450,000 person-hours had been deployed, 10,000 rivets ordered, 450 tonnes of mild steel invested and eight tonnes of Burma teak re-fitted. No corners pruned. Without a rupee’s income.

On the deck

Four, merely putting the vessel on water would reduce it to the level of a ‘water bus’. The vessel – by the virtue of being the only one in India – represented a slice of marine history. The Singhees voluntarily extended the restoration agenda; they carved out underbelly vessel space to curate a museum that would not only showcase marine transportation history on the most commercially important river stretch of the country but also the history of the vessel and its restoration. The story would extend the experience from the ‘here and now’ to the ‘holistic’.

After nearly half a century, the vessel sailed in May 2022. This restoration represented a heritage win. It widened the ‘built heritage’ definition from facades to vessels. It extended restoration from the functional to the premium. It transformed the vessel from near-scrap position to ‘good for another century.’ It adapted re-use from passengering to entertainment.

By the time the vessel was river-ready, an indicative 450,000 person-hours had been deployed

The jury is still out on whether the returns from the restoration will even match the prime lending rate prevailing in the country. Even as returns may lag the conventional ‘post tax 6 per cent’ minimum acceptable, the emotional returns have already transformed the family’s public standing. Even as the Singhee family built 65 vessels from scratch in its multi-decade existence, it is the restoration project of the last three years for which they are now publicly known.

When G20 event location scouts chanced upon this vessel, they asked, “Where have you been?”, cancelled their bookings at a city-based five-star hotel and hosted two events on water.

A visitor from the British High Commission called her 87-year-old wheelchaired father: “I have seen something so crazy here that we might fly you down to see what your generation left behind and how someone has restored it.”

The vessel is an object of awe. The vessel is in the process of redrawing the city’s dining entertainment landscape. The vessel is shifting the needle of the city’s heritage attention to terra aqua. The vessel is graduating the rust recall of vessels to chic. The vessel is a showcase of how the city’s heritage movement is broadbasing. The vessel represents an opportunity to entertain against the backdrop of the two night-lit bridges.

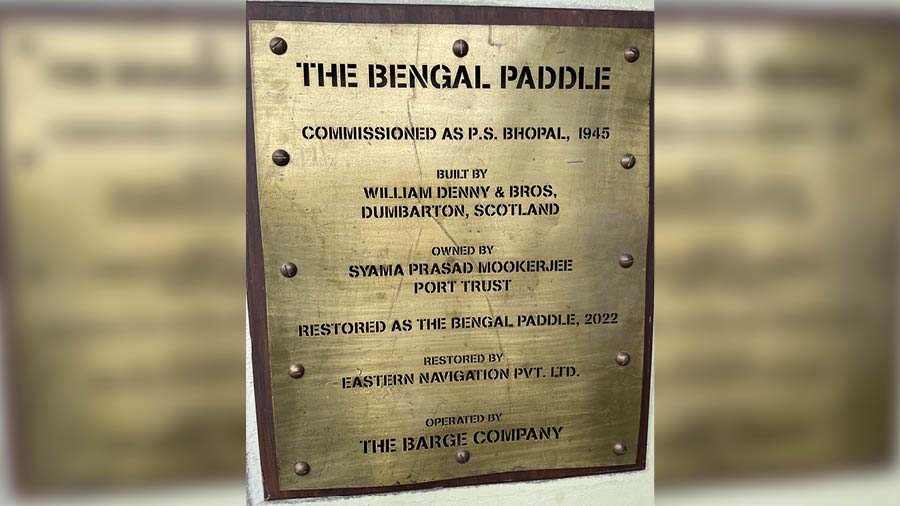

Perhaps it is also time for me to start referring this Dumbarton (Scotland) vessel by its proud name. It is called PS Bhopal 1945. And that it how it shall always be.