Continued from here.

Geological Survey of India

The unusuality of this often-ignored edifice adjacent to the intimidating sprawl of the Indian Museum is that it was constructed at an angle (‘diagonal defiance’) to the arterial Chowringhee by the otherwise fastidiously pucca British. The reason: the structure would inhale the sweeping Maidan breeze and distribute it judiciously across the building in the days when the British complained of the oppressive tropical heat and central air-conditioning was still un-invented. The Chowringhee driveway is perpetually barred. When you get to the Kyd Street entrance for a dekko, the gate security is likely to ask ‘Permission?’ That is how the story of a remarkable architectural edifice does not make it to even the longlist of the longlist of must-see places — even for those who live in Calcutta.

The trick to appraising its carat quality is to walk around with accompanying literature. Read and respect. A former member (select British class, not boxwallah) described: “On the ground floor, the four arms of the Cross housed the billiards room, the administrative offices, the library, and chambers for the accommodation of temporary visitors. The octagonal space, from which the arms of the Cross radiated, was used as the members’ bar. On the first floor, the arms of the Cross were occupied by the dining room, the kitchen, the card room and the reading room. The space above the octagonal bar was open to the roof and provided an entrance lobby at the top of the main staircase to the public rooms.”

To go to see this relic today — disused, what a waste — is to admire what that ‘octagonal space’ must have been in its prime time with the light tunneling down the atrium; the extended marbled stairway that must have been the creation of a Mackintosh Burn architect who had never heard of ‘osteo-arthritis’; the underground surang (as Asrani in Sholay would have startlingly referred to the tunnel) that was used by the angrez to dispense justice and allocate the evidence for anonymous transportation to the river (so goes the unverified whisper). I dream that one day the top person of Geological Survey of India will open the doors of this showpiece on Saturdays for public access so that I may be able to post pictures on social media and then you may come to the conclusion that ‘That fellow who wrote in My Kolkata was not fibbing.’

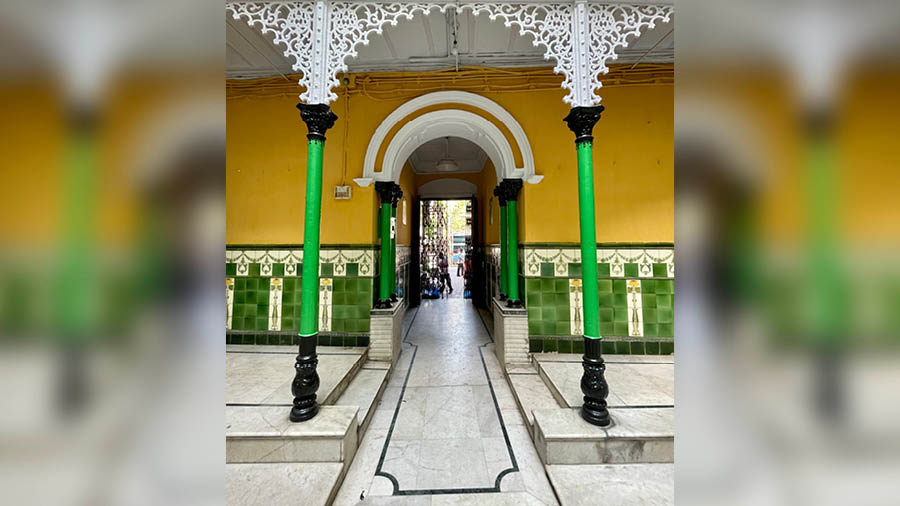

Sen Bari

Closer to the intersection of Amherst Street and BB Ganguly Street are the twin showpieces of the descendants of the legendary Gauri Sen (‘Laagbay taaka, debey Gauri Sen’). One is a residential premises; the other a mandir (not contiguous but a short walk from each other). The first thing that may strike a visitor is the state of perpetual maintenance; the premises is painted virtually before virtually every Durga Puja, so it looks as if it was housewarmed just the other week; the squareness of the property; the two vertical mosaic design representations at the entrance; the cryptic name plate (‘Sen’), the friendless of the owners (I have never heard ‘Ekhon na! Porey aashben!’); the immaculate condition of the properties that provides me an insight into the aesthetic refinement of the homeowners; the ability to get a perfectly symmetrical picture of the mandir when you look at the sky from the courtyard centre point. I have done it a few times already but there is a voice inside that keeps insisting ‘Go shoot and see whether your neurons are still steady. Each time I pass Amherst Street, I tell Jhaji my chauffeur ‘Sirf ek minit’, run in with the phone in camera mode, arrive at the centre point, shoot, examine the results and conclude: ‘Wow. I am perfectly healthy of eye, neck, nerve and arm!’

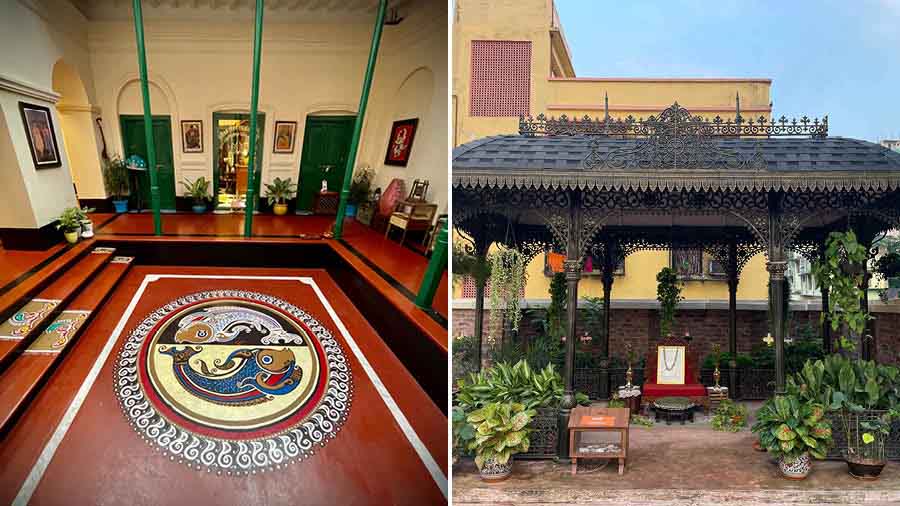

ISKCON House

The mandatory ritual at ISKCON House off Raja Dinendra Street (not to be confused with other ISKCON properties) is to examine the pictures of what this property was five years ago and what it is now. It is a primer on what owner’s pride can do for all of us; it is a primer on how crumbling properties can be turned around; it is a primer on how stories can be re-ignited to paint pictures on what must have been; it is a primer on how specific spots can be transformed into ‘quasi-shrines’ (the spot on the terrace where Swami Prabhupada seeded the concept of the ISKCON movement in the Twenties); it is a primer on how the red oxide zameen can be brought back into circulation if one cares to look around for this endangered skill across Bengal; it is a primer on how one may create real-life feel in rooms where the Swami lived by putting a real-sized installation of him on the bed as if he is about to say something. My recommendation: sit in the ‘well’ of the property and meditate. Once you are ready to open your mortal eyes to the world, walk three minutes to Shree Parsvnath Jain Mandir to be morning-dazzled by the chipped mirrorwork and then on to Calcutta Bungalow another few minutes away to soak in the spirit of the 1900s.

The Che Guevara wall

In Calcutta, the remarkable sits alongside the mundane waiting to be discovered. In the bylanes alongside The Bhawanipur House (restaurant) there is a CPM local office. On the pavement-facing wall of this premises is a commissioned painting of the universal poster boy of egalitarian society (‘aamader Che-da’) by Sanatan Dinda. For all those who flit between art galleries or attend wine-cum-cheese parties expounding on ‘The latest Paul Klee show in Paris the other day…’ do ask your Jhaji-equivalent to de-accelerate, take a picture without getting off the car, capture the signature and send our man a message: ‘Sanatan! Have not seen you in a long time. What lovely work on a Bhowanipore street! I spent hours watching it. Can you do a similar kind on our external wall?’ Sanatan will message in less than four minutes. Guarantee.

Bengal Chamber of Commerce and Industry

One of the better-told stories of Dalhousie (I must get around to referring to it as ‘BBD Bagh’, what to do) is that of the BCC&I showpiece. Most visitors will be wowed by the marbled staircase as soon as one enters the building. There are other jewels secreted away: the room of the President on the second floor with a grandfather’s clock in mint condition; the framed documents signed in longhand with a quill that make blink-worthy reflection pictures; the polish on black wood with golden door knobs; the woven cane seating of old world chairs; the pictures of the ex-Presidents angled meticulously parallel to the stairs; the reflection of the overhead lighting of the conference rooms on long tables (I couldn’t find any table that seats less than 24); the two staircases at the back-end of the premises that provide multi-storey top-down shots; the frosted glass through which one can shoot blurry silhouettes; the humidity clock in one of the conference rooms (never knew such a thing existed); the brass plaque on the ground floor with the name ‘Clive’ in the middle and closest to the eye so that it figures prominently in every symmetrical picture (I love the British).

My only recommendations: if only they could remove the vinyl plastic advertising the Lunch Room from the main entrance and started a service that enabled social media photographers to shoot the premises three days a week. That would be a service to the tourism sector, which in turn would benefit commerce and industry. Think of it.