The wind was in excess of 50kmph. Krishna stepped on a 3-inch bamboo scaffolding 60ft in the air. Even after having been in the business of lights installation for more than 10 years, Krishna whispered to no one in particular: “Jo bhi ho, neeche nahin dekhega!” And having just uttered these words, Krishna felt safer. It was going to be just another day at the office.

Except that even he knew that it was not. The road below was 40m wide. It was long enough for one to see at least a kilometre into the distance. Around 50 cars on average passed every 60 seconds on one side of the road. Another 50 on the other side. Then there was a car using the horn. There was someone trying to overtake.

Even if he tried to tell himself “Neeche kuch nahin hain”, he knew it wasn’t true. This was one of the biggest challenges in his life as an electrical assistant using bamboo poles to climb to different levels to place lights.

The bamboo scaffolding

He clipped his safety belt to the bamboo scaffolding; he said a silent prayer extracted from the Hanuman Chalisa and climbed; one step closer to the top of the St. James Church spire.

He could feel a series of changes happening within. A rippled nervousness through his intestines. The knees trembling. The feet freezing every step before he could summon the courage to put the next step forward. The mind telling him “Bach ke!” in repeat mode.

On top of this, he had to work. By going into his memory of all his practised motions. He bit into the electrical cable from the side of his mouth. He held the cable between the thumb and index finger. Then climbed, one bamboo rung after another.

One would have concluded that this Everest-like expedition would be to install a range of lights. And that is the irony. All this for only one last light on this 162-year-old church. “Badmaash bhara wala!” he hissed. “Why couldn’t he add just four more feet of bamboo so that I could have climbed higher?”

He got both hands off the vertical bamboo, balanced himself by habit and instinct, extracted tools from his jeans pocket, fastened the clip to the façade and then — like a grandmother threading a needle — inserted the power wire through the arched clip. Then Krishna took the 1,000mm linear grazer (a 1,000mm light with a special lens to throw a narrow powerful beam over a long distance) that had been tied to his back and placed it across the base of the spire. Until it was settled there. Until it would not move.

By night

Then Krishna went through his discipline. Fastening checked. Angle checked. Connection checked.

Krishna whistled to his counterpart Akshay watching 60ft into the sky checking his every move. The counterpart hoped that the angled light would be just right so that it could illuminate the top of the 15ft spire.

He wiped his sweat. Then hit the MCB. And then! The 15-degree 45-watt grazer LED shot a beam to the top.

For the first time in 162 years, the metal crucifix atop the St. James Church was now visible. It could be seen by thousands each time they looked up at the church.

Krishna began the climb down. “Dheere dheere!” he kept telling himself. He would not look at the road. He would not hurry. He would not think this was easy.

History of ‘Jora Girja’

St. James Church — between St. James’ School and Pratt Memorial School — dates back to the 1860s. This Gothic church is possibly Kolkata’s only twin spire church rising to 174ft. Better known as ‘Jora Girja’.

The façade of the church represented an irony. Only the top of the church — the spires — were visible to passers-by. The rest of the façade was covered by unplanned tree growth. We (Mudar Patherya’s The Kolkata Restorers funded the illumination and Tushar Bhala, head lighting designer at Kolkata-based Hind Lighting, was the chief lighting designer of the project) took an entrepreneurial gamble. On the one hand, the illumination of the complete church facade represented a waste as it would never be visible; on the other hand, there was optimism that whenever the municipal corporation pruned the leaf cover, the façade would be visible. The latter optimism prevailed; a gamble was taken.

The spires of the church

The first architectural element that we noticed was the flower-shaped window backed by circles of stained glass on the church façade.

The front façade was segregated across levels. Level 1 comprised the windows. Level 2 comprised the verandah. Level 3 comprised the spire and a crucifix atop each spire.

This segregation enhanced the clarity on what needed to be illuminated.

Approach plan

The triangled façade that supported the two spires needed to be illuminated. The lighting team used simple blasters to cover a large spatial spread without compromising lighting intensity. However, the light was not adequate to illuminate the crucifix above the triangle. It was lost in the blackness of the night. We couldn’t place a small light immediately in front of the crucifix as it would have affected the visual design. So the lighting team did the next best thing — and here it becomes interesting: they placed a powerful beam on the railing of the church that was angled upwards on the crucifix. The counter arguments were two: what if the beam did not reach the top across a distance of 40ft; what if someone accidentally nudged the light and no one realised that the beam was not reaching its intended point for days or weeks.

Making sure that the crucifix was not lost to the blackness of the night was a challenge

Eventually the crucifix was illuminated with a long throw from the first floor using a 20-watt fixture — only 20 watts! — with a 5-degree beam angle and specialised lens; this empowered the light to travel approximately 120ft and be focussed only on the crucifix.

The execution challenge

The challenge of illuminating St. James Church lay in its diversity and complexity. The church was large at one level — broad and high. The church is unusual in its frontal façade, which is not a straight-faced façade but one which is triangular and relatively low. The church has two active sides — the front and side facades — making it imperative to illuminate both. The church façade is embroidered with a sequence of stained glass panels, ensconced on the outside by vertical arches. The church is supplanted by two large spires, which are not the usual slim rounded types; these are structural square solid-type, sending out a dominating message that ‘We stand for strength and firmness.’

The church is unusual in its frontal façade, which is not a straight-faced façade but one which is triangular and relatively low

The illumination of such a church required more than a simple halogen-driven approach: place one large light at the bottom and blast light onto the facade. The façade needed to be ‘embroidered’ — different lighting approaches for different points.

The challenge lay in the execution. The bamboo structure had to be raised to the top of the spires. Linear grazers needed to be placed beside the facade for dramatic uplight that would run across the façade surface; this warranted a 140ft climb for installation. Some scaffolding climbers took one look at the street below and felt a creeping nausea, some ventured ahead but had their knees tremble, some prayed and simply said “Hum se nahin hoga!”. Eventually only two climbers could climb and install 15 lights across the two towers. This is what we eventually settled at: for the first spire level, we used a linear grazer with a 45-degree angle; for the second spire level, we reduced the linear grazer beam angle to 36 degrees; for the third level — the 45ft high spire end — we used linear grazers at an angle of 15 degree to ensure that the beam reached the top after travelling the angled facade.

Challenge of the stained glass

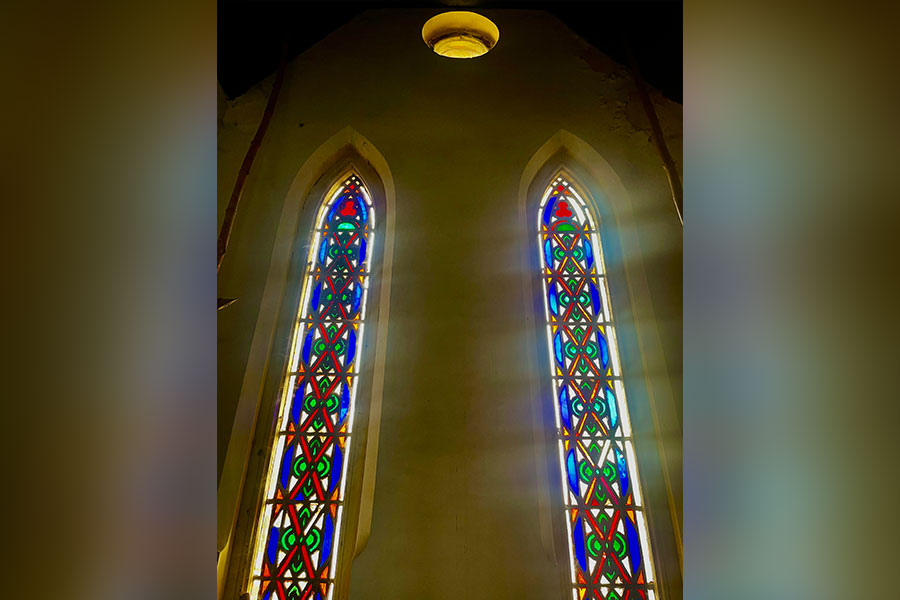

For more than a century and a half, the stained glass at St. James Church served an internal function: it was installed for the benefit of the devotees who came for Mass during the day. As dusk descended, the power and the glory of the stained glass declined and faded into the blackness of the night.

This was a tragedy; the right side of the church has 10 French windows with stained-glass panels with a circular aperture between each window that completed the integrated design. What the church needed was a reinvention; even though electricity was a growing Kolkata reality from the start of the 20th century, any probable illumination suggestion would have been shot down on grounds of cost.

Light streams in through the stained glass

Until February 2024. The Kolkata Restorers recognised the irony; the LED revolution of the last decade now provided a light for every application across a range of sizes and prices, moderating recurring costs. All that was now required was to shift the attention from the outside-inside to the inside-outside. When complete, this would make the church’s stained-glass panel collection a potential 24-hour illumination attraction.

Here came the next challenge: whether to graze these panels from the top or the bottom as the illumination would never be uniform — closer to the panel and less the further the light travelled along the vertical line. Any attempt to illuminate the stained glass from outside would only prove to be a reflection — counterproductive to someone seeking to observe the façade (making it imperative to illuminate the stained-glass panels from the inside).

The stained glass at night

This is how we responded: we hung vertical steel angles from the ceiling inside the church on which we could place angled lights that would illuminate each vertical stained glass. To illuminate the stained glass from the inside to create an external impact warranted a strong light source. The challenge lay not in increasing the power or wattage (which would have been easy but would have increased recurring electricity costs). The solution that arrived at was the use of only 24 watts per stained glass panel but with a difference — a concentrated beam instead of the usual wide sweep. Here, too, we could have taken one light but that would have proved ineffective given the vertical 10ft height of the stained glass. We addressed this challenge with two 12 watt spotlights concentrated into a 15 degree angle, ensuring that all the light wattage would be focused only on the stained glass and not on stray on the adjoining walls (‘light spilling’). One spotlight would highlight the upper end of the stained glass; the second would be angled on the window middle and bottom.

The complexity of getting the right angle had been addressed. We now needed to arrive at the right colour temperature. This was a critical challenge: the presence of around half a dozen colours within each panel made it imperative to arrive at the right temperature that would reflect the faithfulness of each colour type (neither too red nor too blue). After trial and error, we zeroed in on 2700 Kelvin: this would enhance the red within the stained glass derived from the copper content within the stained glass without over-tinting the other colours. The result was that the red of stained glass did not bleed, but sent out a controlled output instead. When the 12 stained-glass panels were illuminated in a sequence and one stood outside the church to appraise their impact, the result was a pleasing-to-the-eye impact that could emerge as the next night tourism driver.

Work never ends

Our work at St. James Church never quite ended. There was a nagging feeling that perhaps the clock face on the right spire could do with a little more illumination; the intricate metal work running across the roof in the shape of miniaturised crosses was illuminated well after everything had been completed and we felt that we had not done justice.

We have stopped going to St. James Church following project completion for this very reason. It is such a fascinating edifice that we will keep discovering new things to do, we will keep finding spots and corners where we could have done better, we will keep going to Father Shreeraj Mohanty with the line “Father, but I have this different idea that perhaps we should…”

It has been time to move to other addresses of this wondrous city and its heritage-rich monuments.

The last word

(Bhala’s) Kolkata-based lighting company Hind Electric has been in business for more than 50 years. What did we learn at St. James Church?

One, lighting a structure with all faithfulness is like peeling an onion; the more you peel, the more of the different emerges; the more of this different needs to be addressed in different ways faithful to its character, shape and scale; the more you customise with light intensity or extensivity, beam throw, colour, lens and temperature, the greater the ‘embroidery’ and the stronger the public recall that “The façade looked so stylishly pleasing!”

Two, the cost. It would have been easy placing five light blasters (my term for halogens) and burning light into the church façade that would have stood out as a neighbourhood neon light. This would have resulted in considerably higher wattage and recurring electricity cost. We did the reverse; we curated lights around corners and applications; we balanced the need for illumination effectiveness with recurring cost and the result is that we covered more than 15,000sq ft with a recurring illumination cost of Rs 103 a day (based on four illumination hours).

That we can do so much for so little at a single location is not the message; the message is that we can transform Kolkata by night at an aggregated cost that may be less than the cost of an upmarket apartment.

Just think.