The stolid façade of the two-storied mansion stands in solitary white splendour in the wispy morning mist. A few peafowls amble about in the neatly-manicured, verdant lawn that fronts the sprawling house. In a corner of the checkered marble verandah, an elderly man, a white wrapper draped around his frail frame, chants from a holy scripture that looks as old as him.

We are at Belgadia Palace in the north Odisha town of Baripada. It was the capital of the princely state of Mayurbhanj – ruled by the Bhanj Deo dynasty for more than 1,200 years. We arrived late in the evening at Belgadia, after a four-hour drive from Kolkata. “This palace has a storied past,” said Mrinalika Bhanj Deo, one of the two sisters who have launched the royal homestay, over dinner.

The royal homestay at night Courtesy: Belgadia Palace

The next day starts off with a drive to Simlipal Tiger Reserve. For most part of the 72-km journey to the entry point to the forest, the drive is through a pastoral landscape dotted with small villages – till we take a sharp turn a few kilometres before Pithabata checkpost. An ancient forest of sal trees, their tall heads in the sky, close in both sides of the untarred road, forming a thick overhead canopy, from which only thin streaks of sunlight filter through. The jungle, even at noon, looks dark and forbidding. The drive is uphill, negotiating serpentine bends. We are amazed to see a handful of tribal hamlets inside this primitive forest, smoke emanating from the humble homes – an assortment of tin, wood and straws. The driver informs that we are passing through elephant corridor, but we only spot hordes of monkeys, red junglefowls and catch a dazzling glimpse of a peacock in the middle of the road, its feathers spread in gay abandon, before it fleets off with an annoyed hoot.

A stream threads its way through Simlipal National Park Courtesy: Mrinalika Bhanj Deo

We arrive shortly at Barehipani Falls. From the upper-floor balcony of the log hut that overlooks it, the cascading waters of the third-highest waterfall in India look bewitching. On the way back, we drive through Nawana valley, its green expanse looking lovely in the mellow afternoon sun, and take a pit stop at Joranda Falls, plunging over a towering cliff in a single drop, spreading out slightly as it falls into the dark valley below.

Joranda Falls, in the core area of Simlipal Courtesy: Mrinalika Bhanj Deo

Back in the palace, we find ourselves in the blue library, lined with ancient cabinets stacked with leather-bound editions of 19th and early 20th-century titles. We gather around a mahogany table and Mrinalika begins the story of her ancestral palace, whose history is entwined with a turbulent love story.

The library of Belgadia Palace Courtesy: Belgadia Palace

In 1889, the crown prince of Mayurbhanj, Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo, met Sucharu Devi in Darjeeling. She was the third daughter of Keshab Chandra Sen, one of the pioneers of social reform in 19th-century Bengal. After a brief courtship, they got engaged.

However, the match was denied by the prince’s conservative family. It was sacrilegious for the heir apparent of Mayurbhanj to marry the daughter of a social revolutionary. The teenage prince had to tie the knot with the princess of another royal family. Fifteen years later, in a sad turn of events, the queen died and the widowed man (now the Maharaja of Mayurbhanj) came back to ask the hand of his boyhood sweetheart, who had remained single.

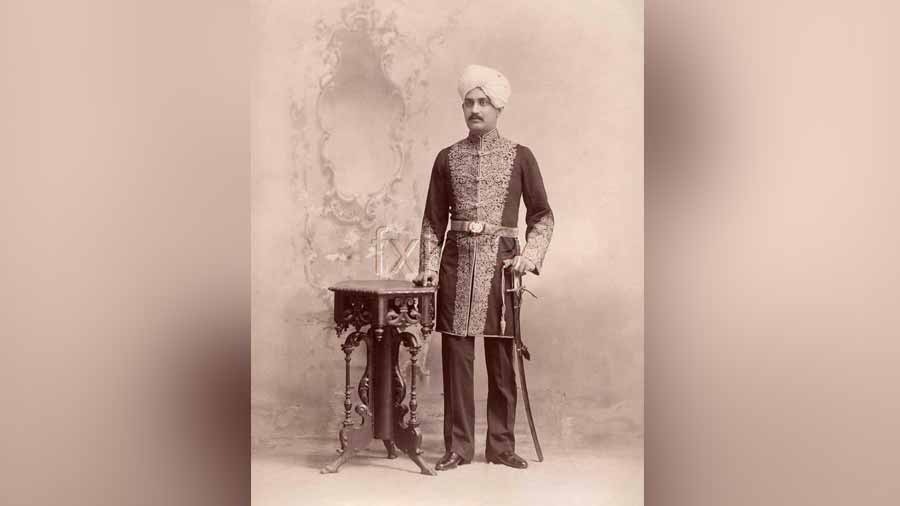

Maharaja of Mayurbhanj, Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo @OdiaHistory/Twitter

“But the new queen was still not accepted by the royal family,” says Mrinalika, continuing, “and though Sriram Chandra remodelled the Belgadia Palace to suit her subtle and refined taste, she only visited the palace after her husband’s untimely death in 1912, and only at the behest of her step-son, who was the new king.” Her visits were more frequent thereafter and some of her guests were eminent painters like Jamini Roy and Hemen Majumdar, whose commissioned works now adorn the walls of the palace.

Next morning, we set off early to Guhaldiha. The tribal village, about 12 kms from Baripada, is home to a community of women weavers of sabai grass, a natural fibre, which grows abundantly in Mayurbhanj district. An untarred road leads us through the village to the cooperative-owned shed where about a dozen women artisans deftly turn the braided bundles of the organic fibre into crafty utility and decorative pieces with their nimble fingers. This eco-friendly tribal art of Mayurbhanj is now a major cottage industry of the state and even the e-commerce behemoths have now joined the bandwagon to merchandise the sabai craftwork.

Women weave sabai grass, a natural fibre, which grows abundantly in Mayurbhanj district Sugato Mukherjee

On the way back, we make a brief stopover at the temple of Haribaldev Jeu, the presiding deity of Baripada. Built in 1575, the laterite stone structure is an exact replica of the more-famous Jagannath Temple in Puri, and houses the sibling trio of Jagannath, Balaram and Subhadra. It has lost some of its old-fashioned charm in the white façade and brightly-painted interiors. The temple hosts a colourful festival during the annual Rath Yatra, when the chariot of Subhadra gets pulled by the town’s women. The next stop is Mayurbhanj Palace, the ancestral palace from where the Bhanj Deos ruled their state. The façade has a resemblance to Buckingham Palace, but most of the 126 rooms now are off limits.

Mayurbhanj Palace, from where the Bhanj Deos ruled their state www.similipal.in

We are back at Belgadia Palace by 11am, its leafy grounds drenched in the mid-morning winter sun. A motley band of young men are waiting for us holding shields and swords, their sinewy frames clad in white dhotis. On a slightly raised stage hemmed in by thick groves of trees, they begin their chhau dance – stomping their bare feet rhythmically, their choreographed movements synchronised with the resounding drum beats. Unlike their Seraikela and Purulia counterparts, Mayurbhanj chhau dancers don’t wear masks, but the movements seem to be more orchestrated. “They are performing the War Dance for us,” Mrinalika informs, and then adds, “this particular dance was composed by Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo for a special show in honour of King George V, when he arrived in Kolkata in 1912.”

Unlike their Seraikela and Purulia counterparts, Mayurbhanj chhau dancers don’t wear masks Sugato Mukherjee

After a sumptuous lunch, where the highlight was a tangy mutton curry spiced up Odisha-style, we set off for Haripur, the previous capital of Mayurbhanj. The morning sun has been replaced by scattered clouds and the last leg of the 15-km drive is through dense woods with a slight drizzle. We walk past a large gate with ASI signage warning visitors against defacing the heritage site and wade through thick undergrowth. A magnificent brick temple stands in the distance, its chiselled architecture oozing a faint crimson glow in the pale light. This is Rasika Raya temple and we are standing right in the middle of the ruins of a massive fort built in 1400 AD, which was so impregnable that it found mention in the Akbarnama.

The Rasika Raya temple in Haripur Sugato Mukherjee

The brick foundation around the temple lead to huge underground chambers, which had a subterranean tunnel – an escape route for the royal family in case of an invasion. “The royal palace, which was inside the fort, has not yet been excavated,” Mrinalika says and points to the open alcoves on the walls of the temple. “These were used to keep fire torches on special nights, when dance performances were held in the temple courtyard.” Darkness descends gently on the fort grounds of the ancient capital of Mayurbhanj, as we try to imagine how magical the night would have been more than half a millennium ago.

How to reach: Baripada town, the base to explore Mayurbhanj is 222 kms from Kolkata (4.5 hours’ drive away). Baripada can also be reached directly by train.

Where to stay: Victorian in its provenance, Belgadia Palace in the heart of Baripada is an 18th-century mansion offering a heritage experience with modern amenities.

Sugato Mukherjee is a Kolkata-based photographer and writer whose work has appeared in The Globe and Mail, Al Jazeera and Nat Geo Traveller, among other places. He is the author of a coffee-table book on Ladakh and a book on the sulphur miners of East Java.