A new awakening of India emerged from Bengal and there is one place in old Calcutta — College Square — that can easily claim to be the epicenter of this revolution.

The educational hub of undivided Bengal

The area around today’s College Square once witnessed a wave of iconic educational institutes that went on to break a new dawn in westernised English education and became the backbone of Indian nationalism. It started with Hindu College in 1817, followed by Sanskrit College that came up in 1824.

Soon, Asia’s first modern medical college, named Calcutta Medical College, was established in 1835. Another iconic institute, the School of Tropical Medicine, also added in line with Hare School. A few miles away, near Cornwallis Square, Bethun College and General Assemblies came up. It was later renamed as Scottish Church College. In 1855, with the establishment of Presidency College and Hindu School, the area around College Street became the education hub of India.

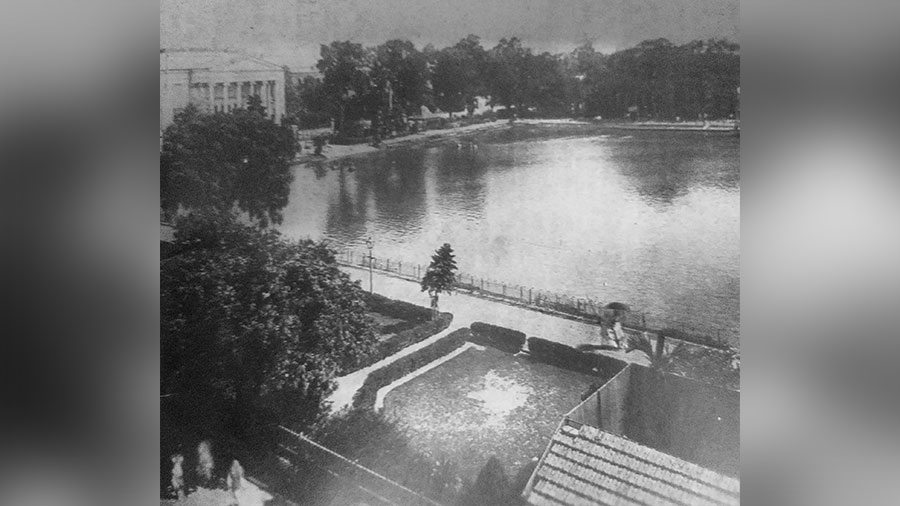

An old picture of College Square from where one could see the Senate Hall and the Sanskrit College

In the year 1854, the court of directors of East India Company proposed to establish modern universities in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras.

Establishment of Calcutta University

University of Calcutta was established in 1857. It was India’s first modern university with a well-structured chamber of councils senate under the leadership of a Chancellor with power to control a large number of schools and colleges covering Punjab to Rangoon. Area-wise, no university of that time had such a huge geography under one university. At the beginning of 20th century there were 82 colleges and institutions under Calcutta University, including nine in Ceylon and two in Burma.

Though the university was formed in January 1857, no official building was allocated to conduct the function of its syndicate and council members.

In the early days, it used the Medical College building and then a rented house in Camac Street. It also used Presidency College and even a room at the Writer’s Building to conduct its operations. The first examination of the university was conducted in Town Hall. According to records, tents were pitched at the Maidan for the next few years to accommodate students during examinations.

Meanwhile, administrative work from Town Hall became impossible because there were offices of a music company and Bengal Race. So the din and bustle of that building was indeed improper for any academic conduct.

By 1861 it was clear that a University could not be run without a proper working place and conducting examinations in tents “under extreme inconvenience” was neither good for students nor for the examiners.

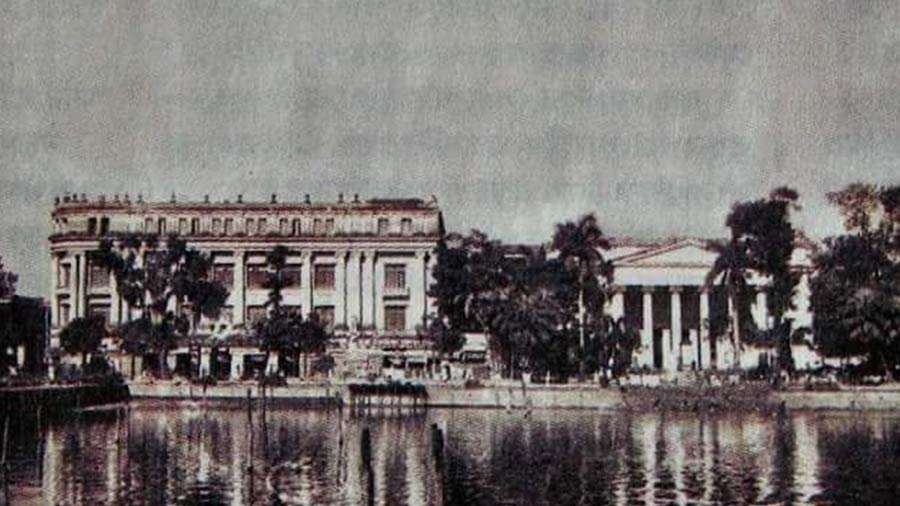

The front view of the Senate Hall on the right

Considering all these difficulties, in 1862, the council decided to build a grand university office that had adequate provision for the vice-chancellor’s office, syndicate and senate meeting room, a grand library, space for a museum, record room, reading room, room for consultation, office of the register and clerks. Above all, the building had at least two grand assembly halls to be used for any purpose of the university.

On January 31, 1862, a committee was formed under Alexander Duff and within a month a gala plan was submitted to the Government. The plan was sanctioned in 1865 and a piece of the land donated by Maharaja of Darbhanga Maheshwar Singh Bahadur was finalised. The land was located between the Medical College and Presidency College and bang opposite College Square.

As soon as the fund was sanctioned by the Government of India, the contract for design was assigned to one Walter Granville who had his signature of excellence in many iconic city buildings, including Calcutta GPO, Calcutta High Court etc.

Plan sanctioned for the Senate Hall

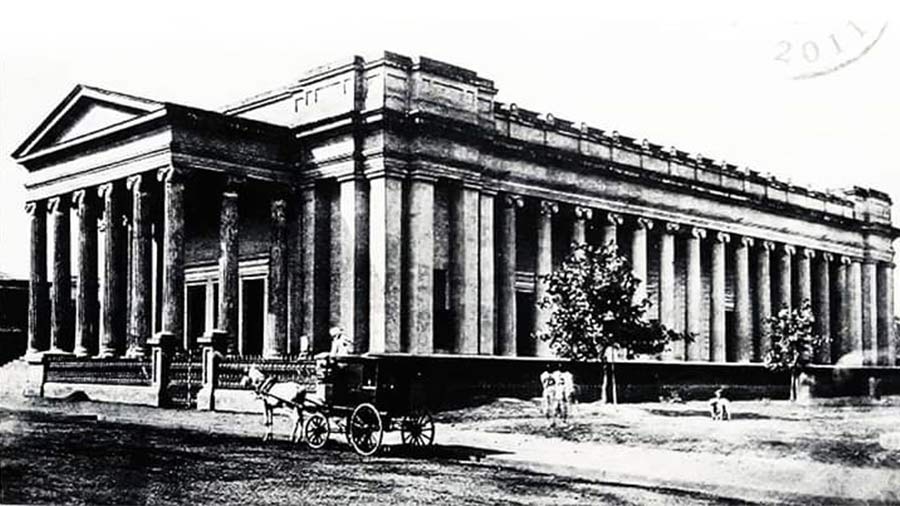

The Senate Hall of Calcutta was designed in a typical Neoclassical style with distinct Baroque elements, and given a form of Greek temple facade on the front, supported by a row of six lightly decorated capital pillars. There were two more pillars on each side to support the extended colonnade or the porch. On both sides of it, a long row of 14 pillars were added for beauty and to demark the corridor that used to run till the end of the building. The hall was equipped with cross ventilation and designed to generate good natural sound flow. A flight of white marble stairs were erected from the pavement. The wide landing was designed before the entry under the temple. Iron railing imported from abroad were used as fences.

It took six years to complete the construction and finally on March 12, 1873, the new building was opened by vice-chancellor E C Bayley, who described the grand edifice as “visible embodiment” of the university and described the day as “new epoch of the career” of the university.

The grand architecture of the Senate Hall

The Senate Hall changed the landscape of College Street overnight. Its mind blowing aesthetic added a European touch in the line of buildings that the street used to house. Later, the Ashutosh building and Dwarbhanga building also came up next to it and with all these the beauty of the street was largely enhanced. Still photos, published in 1926 Calcutta Municipal Gazette, give testimony of this claim.

Postal stamp representing the Senate Hall

The postal stamp released in 1957

In the next 80 years or so The Senate hall became the signature building of Calcutta University. In 1957, on its centenary year, the Indian Government issued a postal stamp in which Senate Hall represented the institution.

The hall witnessed many watersheds of history. It was the main venue of every single important University functions, including convocation, cultural conference, debate, seminars, examination hall, meeting venue, political meeting and more.

It was here in 1937 when Rabindranath Tagore delivered a speech in Bengali for the first time during the annual convocation. Before that in 1932, a student named Bina Das tried to assassinate Chancellor Stanly Jackson.

A witness to many historic moments

In 1934, it was the venue for All Bengal Music Conference. The event was inaugurated by Rabindranath Tagore. Later, Bala Saraswati performed here.

Satyajit Ray got his first public felicitation here after his debut film Pather Panchali released in 1955. Purnendu Patri himself decorated the stair and floor of the hall on that occasion. On August 7, 1941, the procession with the mortal remains of Tagore had a stop in front of the senate hall as a mark of respect.

Immediately after Independence the need for space for the consolidation of all departments came up and the three buildings in College Street were not sufficient enough. Initially, it was decided that the entire university campus would move to Ballygunge, where one Taraknath Palit had donated huge land to the university. However, that plan was not executed.

Meanwhile, some people with their vested interest suggested demolition of the Senate Hall as its roof went beyond repair. They reasoned that the building was a good piece of art but it did not accommodate enough utility. Based on a number of logics, many debatable, the university management finally derived approval from Dr B C Roy, the then chief minister and also a former VC of the university, to pull down the structure and rebuild a multistoried modern building that can accommodate much more records, people and other utilities.

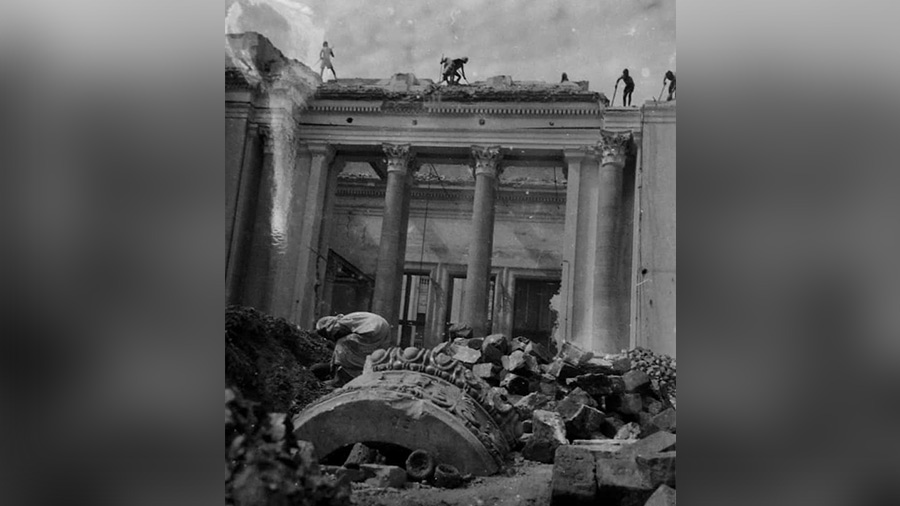

Demolition of the Senate Hall

The Senate Hall being demolished

So the death bell rang during the time of VC Dr Gyanchandra Ghoshin in 1960.

By breaking hearts of many heritage lovers across India, the pillars were pulled down and the grand assembly hall was reduced to rubble. The magical stairs and corridors on both sides soon fell under the ruthless stroke of iron rod and hammer. The agency responsible for demolishing the building found its construction so solid even after 80 years that they found their job difficult. The demolition of Senate Hall became a talk of the town.

With the demolition of the structure, many tangible and intangible memories of Bengal’s awakening were also lost. Many paintings, books, furniture and small memorabilia were misplaced or lost during the time. The archives of ABP and Hindustan Standard issues can reveal the pathetic sequence.

It is believed that lack of people’s awareness to protect heritage and Dr Roy’s lack of interest in preserving history culminated in the demolition of such a superb piece of colonial architecture in the second city of the empire.