Hyderabad is known for its mighty Golconda Fort and the towering minarets of the Charminar. But the medieval Deccan city has even more to offer — including some amazing colonial architecture. The British Residency, the seat of British India’s power in Hyderabad, stands out among them. The main building of the Residency is a colonial style palatial building, popularly known as kothi. The kothi was an initiative of James Achilles Kirkpatrick, popularly known as the White Mughal and immortalised by author William Dalrymple.

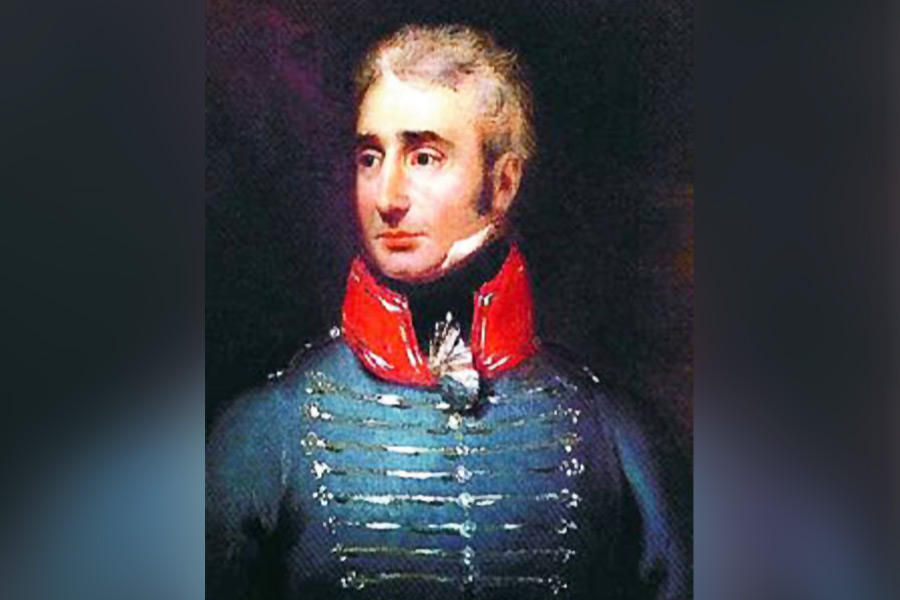

Kirkpatrick was a soldier of the British East India Company. He was also an excellent diplomat and rose to the position of British Resident of Hyderabad. But history remembers him for his love affair and marriage with Khair un Nissa, the grandniece of the Nizam’s prime minister. He adopted the Indian style of living and preferred to dress in Mughal style and smoke the hookah. He was the central character in Dalrymple’s best-selling White Mughals.

The ‘kothi’ was an initiative of James Achilles Kirkpatrick, popularly known as the White Mughal and immortalised by William Dalrymple Wikimedia Commons

The main building of the Residency was the first colonial-style building of Hyderabad and served as the British Residency from the early part of 19th century till Independence. The Palladian-style kothi was complete with a long flight of stairs with ornate pillars supporting a giant pediment. It was designed by Lt Samuel Russell, with funding from the Nizam. Although European in style, it was constructed by local artisans using locally sourced material. Lime and mud plaster covered the brick and stone and masonry with teak wood beams providing the structural support. Located north of the Musi River, the kothi was surrounded by a sprawling campus covering an area of 63 acres.

The northern side of the British Residency Rangan Datta

After Hyderabad joined India in 1948, the Osmania University College for Women was shifted to the Residency campus. Later, the college was renamed as Telangana Mahila Viswavidyalayam and still operates from the historic campus. The majestic kothi started serving as the college auditorium and several rooms were modified as class rooms. Later, the condition of the building deteriorated and the authorities were forced to stop all activities in the building.

William Dalrymple, who visited the kothi during the turn of the millennium, mentions in White Mughals: “Inside the old Residency building, I found plaster falling in chunks the size of palanquins from the ceiling of the former ballroom and durbar hall. Upstairs the old bed rooms were badly decayed.” He further adds: “On the northern front a pair of British lions lay, paws extended, below a huge pedimented and colonnaded front. They looked out over a wide expanse of eucalyptus, mulberry and casuarinas trees,…”

A 1900 photo of the main building Wikimedia Commons

In 2002, the World Monuments Watch programme declared Hyderabad’s British Residency as one of the 100 Most Endangered Sites in the World. No wonder it attracted a lot of global attention. The department of heritage of Osmania University and the Government of Telangana went on with the restoration under the guidance of the World Monuments Fund. After a painstaking restoration work spanning over two decades, the Residency was restored back to its former glory. The restored building was officially inaugurated on April 7, 2022, and was later open to the public.

The grand staircase of the main building and (right) the papier-mâché ceiling of the durbar hall Rangan Datta

Being a women’s college, a prior online booking is required to visit the Residency, which also provides access inside the main building. A long flight of stairs leads to the grand durbar hall. The hall has been restored to perfection and illuminated chandeliers have brought back the former glory. The wooden flooring and decorative mirrors remind one of the colonial days. But the star attraction lies on the ceiling. The intricate floral and geometric designs are the result of a 19th-century European technique known as papier-mâché. A laborious restoration project has brought the art work back to its original grandeur. The durbar hall is flanked on either side by two oval rooms.

An illuminated chandelier Rangan Datta

A grand staircase leads to the first floor, which once housed the bedrooms and guest rooms. This has been turned into an interpretation centre along with an audio-visual room. The audio-visual room screens a short documentary, focussing on the restoration of the Residency. The interpretation centre displays a series of photos, maps and diagrams along with a detailed write-up describing the history of the Residency and Hyderabad.

A British-era cannon on the college campus Rangan Datta

Relics of the British Raj are scattered through the college campus and even include cannons. The Roberts Gate and Lansdowne Gate stand on the east and west of the main building, respectively. On the south is the grand Empress Gate. Several other buildings that have survived have been turned into classrooms and labs.

So, the next time you are in Hyderabad, do visit the Residency for a colonial flavour in the land of the Nizams known for Charminar and biryani.

Visitors’ information

Booking: Online here

Entry fee: For Indians: ₹100; ₹50 for students (ID card required) and children below 5: free. For foreigners: ₹300. To be paid online

Photography: Allowed. ₹100 for camera and ₹50 for mobile. To be paid on spot

Time slots: Monday to Saturday: 10am – 11.30am, 11.30am – 1pm, 2pm – 3.30pm and 3.30pm – 5pm; Sunday: 9am – 10.30am and 10.30am – noon

Location: Located 2km from Mahatma Gandhi Bus Stand (MGBS). Metro access from Osmania Medical College (red line) and Sultan Bazar (green line)