Zaika aur kahaniyan! That’s what defines my Sunday evening in and around Zakaria Street. So, what was it that took me there? Iftar. I was born on the day of Id and was nick-named Eidu. So, my connection with Id or Meethi Eid as we used to call it, is many moons old. But now being a chef, I look at this festival differently and food is, of course, central.

Even though Id shifts by 10 days every year, thus falling in different seasons in different years, the food eaten for Iftar is almost the same. This shows that food of iftar is culturally deep-rooted, has a meaning and thus, has stories. Hence, I planned to go somewhere to listen to and experience some of these stories.

One area in Kolkata which transforms into a hyper hub of activities just before Maghrib (the call to prayer and breaking of the fast), is Zakaria Street and around. I was sure I will find many stories here to hear and taste.

So I took help of a new-found friend, Amir Ali, and took a foodie companion, my daughter, Mishthi. Amir was born and brought up in the area and thus knew each and every gali, koocha and dukaan. He knew shopkeepers by their first names and they all called him Amir bhai. This is not the first iftar walk that I have done, but I wanted this to be different . I wanted to explore the lesser-known places of the area. Not lesser known in terms of popularity, but in terms of branding in the larger world .

Our first stop was at Md Salahuddin’s Adam’s Kabab Shop in Phears Lane, Chuna Gali. A small shop serving the same kebabs for 105 years, as the poster claimed. They have only two shops, the main on Zakaria street and another new one in Park Circus. The iftar menu had three kinds of kebabs and rumali roti. That’s it! Super specialisation and it showed. They specialise in suta kebab and boti kebab though they make biryani and rolls too. What fascinated me was the suta kebab. It takes a lot of skill to put the meat mince on the seekh and then tie it all up with a thread or suta. The seekh is then slow-cooked on an open charcoal grill. When done, the suta is removed and the kebabs are served with some chutney and onion. The flavours of meat and fresh aromatic spices are still printed on my memory. It was mildly spicy but very pleasant to the palate. It had a mysterious sort of floral aroma too. But what made me ecstatic is that it just melted in the mouth. A great first stop and chapter of a story.

Our second stop was at Haji Allauddin Sweets. A 100-year-old shop or rather shops. Interestingly, he has two shops opposite each other. Both serve the same dishes. In one, everything is made in pure ghee and in the other, normal oil. The owner of the shop told me that his great grandfathers believed that good food should be affordable and available to all so they had two shops. They specialise in imarti and gulab jamuns and are mostly sold out by 6pm. He said that there are many people who break their fast only with his imarti. The rush at the shop ratified the claim. He also specialises in samosas (veg and non-veg). But what he offered to me first was something I had never had before. He offered me fritters of potato and spinach. They were semi covered in a batter made of gram flour and probably some rice powder, as they were very crispy. What made them stand apart was that they were fried in desi ghee, and the ghee used was very very aromatic . The heady mix of spices and the umami flavour of ghee turned the humble pakora into a piece de resistance, which I could not resist having in plenty. If the pakora was divine, the imarti was surreal . Perfectly fried, filled with just the right amount of sugar. Imarti straight out of the karahi can be a case study for the number of boxes it ticks in terms of taste, texture and flavour. Specially flavour as it is again made in pure ghee. I could have had the samosas, too, but Amir bhai told me that if we do not rush to our next shop, he will be sold out. I packed the samosas!

While going to the next shop, I learnt the difference between firni and seviyan. I also learnt that fish and chicken fry are now becoming popular for iftar, which was evident from the number of shops selling the same, each in their own style and colour. I saw heaps of dates being sold in grams and kilos. Another unique thing I came across was ladwa biscuits. These look like burger buns from a distance but when you hold them they are absolutely dry and kadak. They are like rusk or dry toast and usually had with tea. I was told that this was an import from Bihar.

So we reach our next destination, Bashir Hotel, a place, I was forewarned, would run out of its haleem if we reach late. There was a huge rush at the shop. While the owner Ahmed was busy at the cash register giving out tokens, there was this gentleman who I can describe more as a ‘dramatis personae’ standing proudly with a huge deg of haleem and pouring out boxes after boxes. This shop serves haleem only during the month of Ramzan. The haleem I tasted here was perhaps one of the most balanced ones I have ever had. A perfect blend of meatiness, spice and wholesomeness, it was a very satisfying and gratifying bowl of goodness. It had a soul. Maybe that is why Bashir bhai does not make it throughout the year. Rest of the year it will just be another commercial dish. But here, in this one month when you make it while fasting, you put emotions in it. You have to have experience it to see the difference.

Haleem is one dish which particularly stands out in this month. There is scientific reason to this. Haleem gives instant energy as it is high on calories. Most of its ingredients are slow digesting but high energy providers. Some types of haleem have dry fruits also, which are great anti-oxidants. The combination of ingredients keeps the person satiated for a longer time. It is because of all these properties that it has become the signature dish for Ramzan. Do you know that Hyderabadi haleem got GI status about 12 years back? It became the first meat product of India to receive a GI certification.

Commercially, haleem was first served in Madina hotel in Hyderabad in 1956. It is said that the Arabs got haleem (or harees as they called it) to Hyderabad. A particular Arab community called Chaush were called from Yemen and appointed to safeguard the Nizams. It is this community which brought in haleem during the rule of the sixth Nizam, Mahbub Ali Khan in 1884. The later Nizams popularised this dish further. Some historians, however, say that haleem came at the time of Aurangzeb when he was conquering the Deccan areas. So the biryani which the Awadhs got changed in Kolkata… did the haleem of the Nizams change in Kolkata too? That’s another story to narrate someday.

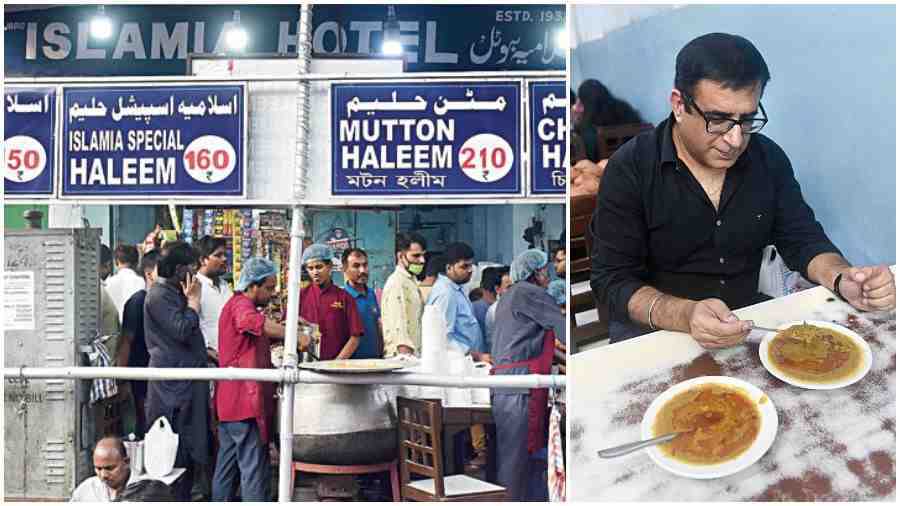

Amir bhai then told me that the haleem trail cannot be complete till we visit Jadid Islamia hotel. This was one place where we took a breather from the swelled-up rush on the streets. It was an honour to share a table with the current owner, Zubair bhai, of the 90+-year-old hotel. He is perhaps the fourth generation running the place. He served us two types of haleem — the original recipe, which was milder but more meaty, and the the evolved one, which was spicier but ticked all your senses in a unique manner. You kept on wondering what would be the spice mix, but the blend is so good that you will keep going back for more. As we heard stories of the place and the people who have visited this place, we were treated to an exquisite saffron firni. It was light as air, just about right amount of sweetness and the whiff of saffron is just what you needed to end your iftar meal. We were about to leave and then it happened. Zubair bhai mentioned that if I, being a chef, would like to visit his kitchen. How could I say no to this offer? Unlike modern kitchens where the restaurant is bigger than the kitchen, he had a kitchen larger than the restaurant. A very hygienic and well-planned kitchen but what surprised me is that the only cooking medium in the kitchen was coal. All the food made at Islamia hotel was slow-cooked on charcoal fire in brass and copper vessels only. Simply surreal in this modern world. Now you know the secret as to how food from such kitchens tastes different from modern kitchens. Talking of secrets, he also showed us the place where he blends the spices in the night, alone.

Our last stop was at Dilli 6. A modern-looking shop but nevertheless crowded. I was wondering why Amir has got me here after taking me to some historical places. We settled down on a couple of plastic chairs on a quieter side of the pavement and saw the whole swarm of people going by, the excitement reaching its peak perhaps, as the iftar time was just 15 minutes away. As I was speaking to Raza Qureshi who worked in Delhi for a few months before opening this place few years back, I realised that the new generation has different tastes and preferences. Having said that, the signature dish of Dilli 6, the chicken fry, was a perfect blend of flavour and science. Science because the chicken was fried to perfection , without temperature gauge pressure friers with automatic cut-offs, and that too in such large quantities. The other most tempting dish in the shop was Asal Tawa Changezi, stewing on a huge iron tawa. The best way to enjoy it is with a sheermal or Irani roti. It’s a makahani gravy… no, it’s a qorma… no, it’s a masala gravy… no, it’s all of the above. Maybe because it’s so formidable, it’s called Changezi.

Well that was my Sunday evening. Well spent listening and tasting stories. I personally believe that these are all part of our cultural heritage. Unique because they are both tangible (the dishes) and intangible (stories and recipes). We need to protect them. We need to talk about them. We need to bring these stories out to the public. We need to create a stage where such storytellers and performers could come and perform and showcase their culinary skills. I am definitely going back again, maybe for Suhur this time. If dusk had so many kahniyaas to tell , I wonder what dastaans will dawn behold.

Pictures: Pabitra Das