Around 2001, a girl named Jaba was born to a family of abject poverty in Piyali, in the South 24-Parganas district of West Bengal. One day, her father told the seven-year-old he was taking her to Kolkata. The girl was excited at the thought of visiting the "big city" and dressed up in her best clothes. When she sat in the train, it began moving in the opposite direction, towards the Sunderbans. Jaba was sold by her father for a couple of thousand rupees to feed the family, and was never seen again.

Jaba was one among many such girl children. Two decades ago, such stories were rampant in the impoverished belt of West Bengal.

Today, the area is home to PACE Learning Center, a school jointly run by PACE (Promise of Assurance to Children Everywhere) and Rotary Club, that has not just transformed the lives of several girls, but the community as a whole at large. My Kolkata paid the sprawling campus – less than an hour’s drive down the Bypass from Ruby Hospital – a visit.

Set up in small shacks near Piyali station, Piyali Learning Center (now PACE Learning Center) has grown to a sprawling campus that accommodates 250 girls

The institute's story begins with Deepa Biswas Willingham, who was born and brought up in Sodepur. In 1959, she left to pursue her higher education in the USA, where she built a successful career in hospital management in California, and retired by 60. That is when a new chapter in her life was scripted.

“In 2001, Deepa began coming frequently to India, and specifically to Bengal, with the desire to do something for her motherland,” says Jayanta Chatterji, president of PLC and a member of the Rotary Club of Calcutta Metropolitan. During one of her visits, Willingham heard the story of Jaba, and was determined to educate girls in the area and empower them. “Her motto has always been, ‘Learning never goes waste',” Chatterji adds.

PLC started as a bunch of rented huts, with just 20 students PACE

Willingham founded PACE Universal and started Piyali Learning Center in 2003 in the residence of her then-cook. In the beginning, the school rented out nearby shacks and converted the huts into classrooms.

She soon realised that the problem went beyond just trafficking, with abuse and child marriage being huge challenges. By 2006, she saw that the school wasn’t growing like she wanted it to, despite regular funding. “Most women here work as domestic help in the city. They leave home at 4am and return at 8pm. The men are either working all day as agricultural labourers, or drunkards living off their wife's earnings. In such a setting, the eldest girl of the family often ends up taking care of her siblings,” Chatterji explains.

An unknown feat in Piyali

In order to combat these challenges, Willingham partnered with Rotary Club of Calcutta Metropolitan in 2007. “At the time, barely 20 girls were attending our school and we had to employ outreach workers to convince parents in the area to send their kids to us for the day. We first pitched the school as a creche to the working parents, where girls would play, and get a bit of education in the process,” he reminisces.

Even in the late 2000s, educating girls was an unknown feat in Piyali and there were no schools for them. To encourage enrolment, the management gave the girls free breakfast and mid-day meals. Gradually, the girls started trickling in and settling down. “We brought in a lot of games, books, art, and music to get them involved. Earlier, they only came for food, but soon they started enjoying coming to school and began showing an interest in education too. In the process, our enrollment numbers also grew,” Chatterji adds.

In addition to food, the school now even provides uniforms, books and free healthcare to its students. “One of our girls had a hole in her heart. We took her to Rabindranath Tagore Hospital for a corrective surgery, and she’s completely healthy now.”

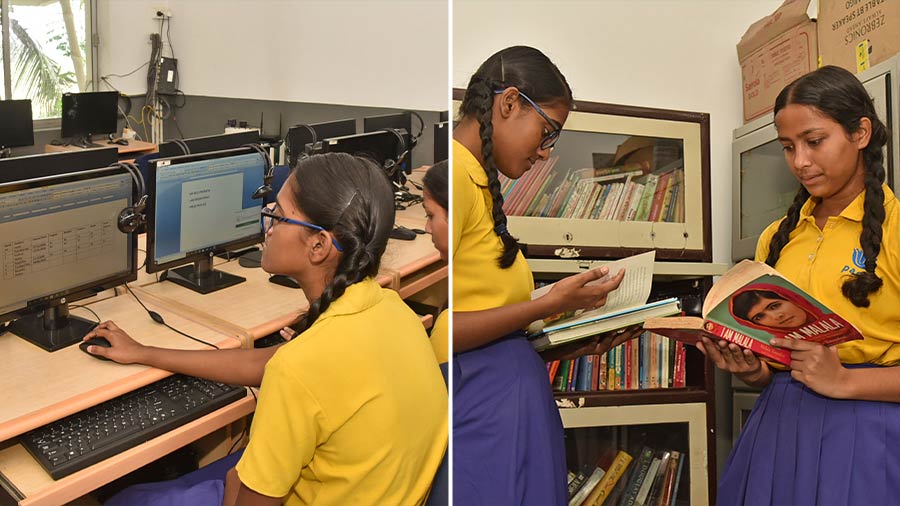

The school tries to provide exposure with several amenities like a computer lab, meditation centre, library and a science lab

By 2009, the school had close to 90 students, and the shacks were getting cramped. Luckily, Willingham had planned for such an eventuality. Even before partnering with Rotary, she had booked the plot of land that the school stands on today. Construction started in 2009, and they moved into their new home of learning in 2013, with 100 students.

In keeping with her vision, the school didn't just want to teach the girls, but empower them too. “We found that just getting girls to school wasn’t enough. Through the girls, we wanted the parents, and through the parents, we wanted the community to undergo a transformation.” After securing the 3-H Rotary Grant that focuses on health, hunger and humanity, the institute helped install 40 tubewells and over 450 toilets for the community.

PACE also started imparting vocational training to parents, and helped scale adult literacy rates in the area. Chatterji also mentions the rise in employment generated by building the new campus of the school. “Through these efforts, a camaraderie grew between us and the community. Seeing our success, more girls’ schools started coming up around here too.”

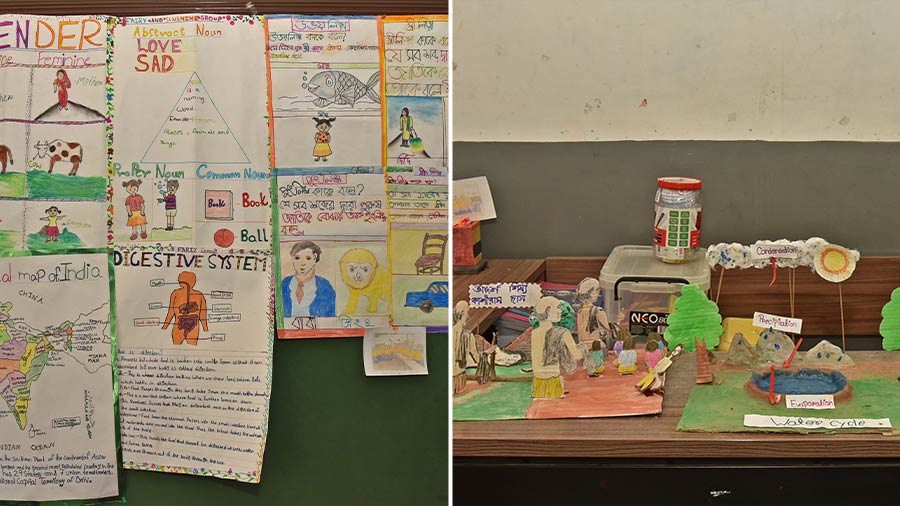

Every classroom in the school has creative projects put up by the students based on their curriculum

Their success also led to an increase in applications. However, the management is firm on not accepting more than 25 girls in the lowest class every year to ensure that the teacher-student ratio remains 1:25. “For 25 seats, we have an application count of around 140. We do multiple checks before granting admission to ensure that selection is fair.”

The system is an elaborate one, which begins with checking if every girl has a BPL certificate. Chatterji adds that since the certificate can’t always be trusted, PACE visits each house and sees their parent’s financial condition. “The girls and parents are interviewed separately, because the parents always talk about how poor they are, but the girls sometimes admit to having TVs, fans and more. The children never lie.” The school gives a preference to orphans, children with single parents, first-generation learners and siblings of students.

‘The girls don’t want to go away’

However, admission is only half the battle won. Chatterji draws attention to the shrinking batch size in higher classes, attributing the dropout to the lure of Kanyashree, a benefits scheme pioneered by the Mamata Banerjee government. “Many people educate their girls here till class 5 or 6, so that they learn English and build their groundwork. After that, they switch to public schools, to avail Kanyashree’s benefits, like the monthly allowance and the bicycle. The girls don’t want to go away, but unfortunately it’s still a patriarchal society.”

(Left) Jayanta Chatterji, the India director for PACE and a member of the Rotary Club of Calcutta Metropolitan, and (right) Jayeeta Chatterjee, principal of the school, both stress the need to educate and empower girls

To combat this, PACE has launched an alternative where they try to provide college education to every girl who passes Class XII. “Last year, four girls availed of this provision. All four are studying in colleges under Calcutta University, and their fees is covered by PACE,” Chatterji says.

His face breaks into a big smile when he talks about a girl from Piyali who cracked the GNM entrance exam and is now being supported in her three-year nursing course by them. “The girl was very soft and shy, but when she met me during Poila Boishakh, I couldn’t recognise her! She has become so confident, and was telling me that she plans to complete this course, take up an internship, do another two-year nursing certification, and become financially independent.”

Tackling cases of elopement

Another frequent contributor to drop-out cases is elopement. The school functions from 8am to 3.30pm. The girls go home after that, but both the parents are still at work. During that time, romeos from the locality are all roaming around, trying to court them, often leading to cases of elopement. In order to combat this, the school has launched a two-point plan. The first was launching a series of after-school enrichment courses, where the students were engaged in activities like yoga, music and sports from 3.30pm to 4.30pm.

The school makes learning enjoyable for the girls by giving them ample greenery to play in

The second was to enhance exposure to the outside world by taking them on field trips to places like Science City, Birla Industrial & Technological Museum, and Alipore Zoo. The more they interact with the outside world, the more these elopement cases drop.

With the help of several matching and global grants, the school has also introduced amenities like science and computer labs, a sewage treatment plant, and a water filter. In order to raise funds for more such reforms, PACE holds an annual Bollywood Night too!

Mid-day meals, and after-school enrichment courses

To try and provide holistic learning, PACE has put together a student exchange programme where pupils from American schools routinely come to Piyali to study. In 2018, Chatterji even took three girls from Piyali to California for three weeks, where they studied in a school and lived in the homes of their peers. “You would assume that girls who have grown up in a village in Bengal would be shocked if they went to California, but they had already made a lot of American friends over the years through the exchange programme, and for them they were just Cliff dada and Sara didi! They adjusted to the culture really well and left behind an unbelievable impression. Before leaving, the girls even gave their American peers a glimpse of mehendi!” The girls learnt organic farming techniques in the USA, and Piyali has encouraged all of them to adopt a tree. They have also raised $56,000 dollars for 56 palm trees on the campus!

Besides the trees, the school routinely encourages them to take the lead. This is visible in how the students have painted several walls and benches on campus, inspired by themes like Abol Tabol. Members of the school’s Interact Club also do a lot of work in the community, including teaching kids how to speak and write in English, and spreading environmental awareness by distributing dustbins.

The students have painted many parts of the campus themselves to reflect their ideas

For Chatterji, the core driving force is seeing the girls becoming the best versions of themselves. “Five of our students completed the GDA course and have been absorbed by Ispat Cooperative Hospital in Sonarpur. The hospital is really happy with them, and wants to hire more such girls. One of our students is preparing for the NEET exam and wants to become a doctor. These dreams aren’t just theirs, but ours too. The reality of how far we have come, is what pushes us further.”

Skill development is the priority

The next big leap for the school is to be affiliated to the WBBSE Board. “The affiliation is a necessity for students now if they want to sit for college exams and compete with other students. The NIOS board can create challenges for admission to CU and other varsities,” says Jayeeta Chatterjee, principal of the school. She adds that skill development is their primary priority, in order to help the students become job-ready.

The management also has an eye on expanding the infrastructure. “Currently, we can accommodate 250 students. If the expansion goes according to plan, the number will go up to 600. If the response is good, we are even open to holding classes in two shifts, so that we can reach 1,000 students. But we still believe in quality over quantity, and don’t want to sacrifice our teacher-student ratio. Our vision is that every girl who passes out of this school becomes independent,” Chatterji smiles.

Since its inception 20 years ago, PACE Learning Center has educated 800 girls. So, 800 Jabas have been saved.