He could be a conquistador, or a tango dancer, although he sat worlds away from Central or South America, at the royally luxurious Mandarin Oriental Bangkok hotel. Endowed with the effortless ease of a prince, he turned what looked like kohl-lined eyes to me. This was the great Peruvian novelist whom I both loved and had some discomfort with. Loved because of the courage of his pen, where he unashamedly wrote angrily about the brutal self-aggrandisement of American interests — corporate and the CIA — in the Latin American countries; and was uncomfortable with his representation of women’s bodies.

I remembered the explicit lines from his book Feast of the Goat as I returned his smile: “Occasionally a man would stick his head out from a vehicle and her eyes would meet a pair of male eyes that look at her breasts, her legs, her behind. Those eyes…In New York nobody looks at a woman with that arrogance anymore. Measuring her, weighing her, calculating how much flesh there is in each one of her breasts, and thighs, how much hair on her pubis, her exact curves of her buttocks. She closes her eyes feeling slightly dizzy. In New York not even Latins — Dominicans, Colombians, Guatemalans — would give such looks. They’ve learned to repress them. Realised they mustn’t look at women the way male dogs look at female dogs, stallions look at mares, boars look at sows.”

As I mull over the great novelists who write about Latin America — Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Zulfikar Ghose — I realise that Vargas Llosa’s representations and creation of the female characters are somewhat typical of the male gaze that reflects the masculinist, dominating culture of male self-gratification in that ethos.

Today, some years after that memorable conversation, as I excavate and re-explore novels such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, with young Masters scholars, who are extremely sensitive about the issues that are unpackaged in the classroom both in Toronto and Kolkata, my comprehension of the keenly polar gender dynamics and objectification of the female body by Latin American writers is much less rabid, especially when examined under the cultural lens.

It is still disturbing though, that although these remarkably gifted male writers point out the abhorrent inequality between the coloniser and colonised, they mostly remain unenlightened about treating the women with dignity that they wish from the white masters. In the representations in their novels, the lack of equality is disturbing. More compassion and respect would be the way to go.

The highly imaginative author, majestically creative, sat upright on a gilt sofa embossed in Thai silk. We were at the opulent The Authors’ Lounge, that emanated literary history like no other space on the planet. This is where Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene, Norman Mailer and so many others had written or visited or arrived for rest, relaxation and recharge. Vargas Llosa was there to deliver the annual lecture at the S.E.A. Write Award (Southeast Asian Writers Award).

Although he had a comfortable upbringing, he was constantly haunted by the spectre of domination and masculinist repression by the US and this drove the engine of all his works. Mario Vargas Llosa was born in 1936 in Arequipa, Peru’s second largest city. During his childhood in Cochabamba, Bolivia, and Piura, a city in the north of Peru, he believed that his father had died. However, this was a lie told by his mother to conceal their tortuous separation.

In 1946, his father suddenly came to take him away from his mother’s parents. They went with him to Lima. This led to an abrupt change in Vargas Llosa’s life, from a gentle feminine environment to the hostile treatment of an authoritarian father. He was to discover fear, injustice and violence first hand. And with the political ethos in Peru sharpening and all bastions of normal life crumbling, the young Vargas Llosa realised his domestic dysfunctionality was reflected in the larger national crisis.

At the time Alexander Dumas and Victor Hugo’s writings kept the young man absorbed. The Peruvian dictator Manuel Odria rose to power in 1948 and over the next eight years, while Vargas Llosa studied law and literature at the University of San Marcos, Odria legislated rigid controls on social life which tried to erase individuality, which, in turn, brought a wave of frustration among Peruvians.

This period later inspired his novel Conversation in the Cathedral, published in 1969.

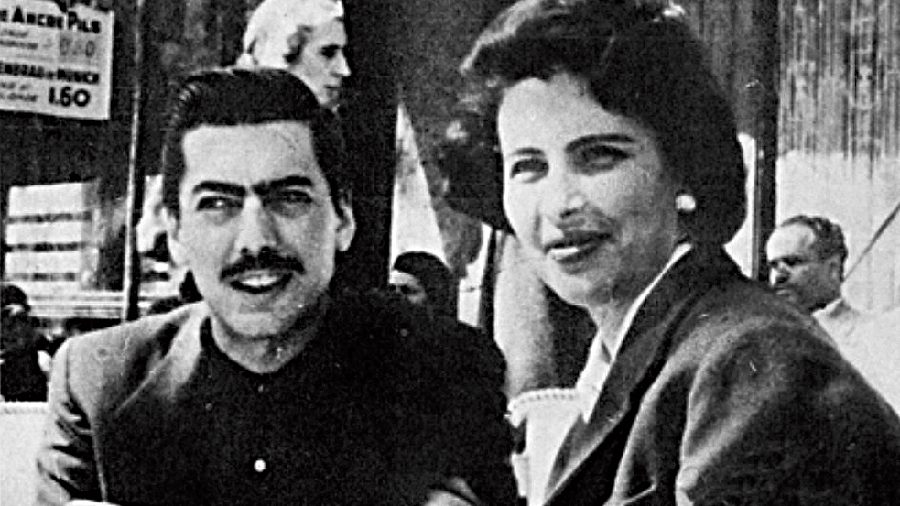

Personal freedom was the first principle of young Vargas Llosa’s life. And all his literary works were a condemnation of systems which tried to stifle personal freedom, The Time of the Hero (1963) evinces his loathing of manifestations of power and the absence of law which enables the strongest to impose their will. The inspiration for this novel was the time he spent between 1950 and 1951 in the Leoncio Prado Military Academy, where he was sent by his father to stifle his literary ambitions through military discipline. However, Vargas Llosa managed to rebel against his father, not only pursuing a writing career, but as signposted by many of his biographers, also marrying his maternal uncle’s sister-in-law Julia Urquidi, who was 11 years older than him and divorced.

Mario Vargas Llosa with first wife Julia Urquidi

I pointed out that his unflinching faith in democracy, with pluralism and a free press, is well known. However, did this kind of steadfast devotion to truth landed him in great trouble? “Oh, without any doubt,” he said with a laugh.

“This is inevitable. If you keep mum, it is no problem but if you participate and defend what you believe then you have to pay the price,” he maintained.

How did he break the publishing ceiling and break through as one of Latin America’s greatest literary exports? Vargas Llosa maintained that it was sprouting wings and moving away from the parochial and financial limits of Peru that changed his life drastically in 1958, when he won a grant to pursue a doctoral thesis in Madrid.

“Before I went to Europe in the ’50s, I didn’t dare be a writer. In the Latin American countries literature was an activity that was so marginal to the mainstream of society that it was impossible to make it financially viable. The thinking was, during the whole week you worked in a proper job as a lawyer, a teacher or a journalist. On Sundays and holidays you could write.

“But I realised quickly that if you keep writing at the margin of your life, and let everything else get in the way, you will never be a writer. So it was in 1958 when I went to Spain that I decided to dedicate most of my time and energy to writing.”

Vargas Llosa as a young writer in the Seventies

Today, happily married for the second time, he devotes almost the entire day to work — conceptualising, organising, and thinking of plot and character. Working in a public library makes him feel most inspired. Vargas Llosa began writing plays in the 1980s, but it was not until 2005 that he decided to take to the stage himself to portray his characters. Aitana Sánchez-Gijón, the actress who accompanies him in this new adventure, has described him as a promising young actor.

I had prophesied in 2002 when we met that he would win the Nobel. At that time he was working on The Way to Paradise, about Flora Tristan, a women’s rights activist and artist. He commented: “Men are not reading anymore. If literature survives it will be because of women. This is a fact I encounter every time I sign books, go to bookshops and encounter readers in libraries.”

I asked him if he expected to be the winner of the Nobel Prize in 2002, which was to be announced just two hours after our conversation and which, in fact, went to Hungarian writer Imre Kertesz. With absolutely no hesitation and with a sweeping wave of his hand he said, “No. That is a lottery, I don’t want to think about that as a writer. And anyway, how can you predict a winner in a lottery.” But somehow, my premonition had proved right.

A story of human tragedy

Hundreds and thousands of readers worldwide have been introduced to the vexed history of Central and South America through the fiction of Mario Vargas Llosa. His most recent novel on the US’s intervention in Guatemala and the volatility that followed a coup orchestrated by the US, packs a punch and traverses the past and present continuously. Written in 2018 in Spanish, and translated in 2019, the story is a masterpiece of historically driven creative fiction.

It is an addictive read because it speaks of the human tragedy that history witnesses. Greed, lies, betrayal, abandonment, brutality, lust — all the X-factors that are causing the present murder of innocents because of the tyranny of a behemoth against a minuscule sovereign state — have a human face in Harsh Times.

The cover of the novel

The Nobel Prize awardee is known for his shooting-from-the-hip technique, where he fiercely tells the story of Colombia, Peru, The Dominican Republic, and other nation states that the US corralled into submission through either creating a corporate hegemony, collusionism or coups.

Vargas Llosa’s truth-telling through his fiction is synonymous with talking back to the centre, even if the centre is the all-powerful United States of America, where, in the ’50s the CIA was a law unto itself. In the course of our conversation the author reminded me that: “Being in a cast and the mastering of a technique is missing the point about being a writer. It’s something moral, a kind of commitment to what you believe to be the truth that makes you passionate about writing.”

“A writer’s job is to defend with conviction and integrity, rigour and imagination, what he believes in. That is the kind of honesty a writer needs to have, ” Vargas Llosa stated categorically when we began speaking about the courage needed by a writer to critique political brutality or disregard for humanity.

“Writing a novel is a ceremony similar to a striptease,” he had once said. “Just as the girl in the spotlight casts off her clothes, and reveals her secrets one by one, the novelist bares his own intimate being through his novel.”

Where Mario Vargas Llosa locates his novel is against the backdrop of the Eisenhower administration’s intervention in Guatemala — one of the most closely studied covert operations in the history of the Cold War. Yet we know far more about the 1954 coup itself than its aftermath. Vargas Llosa uses the concept of “counterrevolution” to gesture towards the instability, mistrust, horror and bloodshed the CIA had created in the ’50s in Guatemala in his fictionalised account of the irreputable Eisenhower administration’s efforts to restore US hegemony in a nation whose reform governments had antagonised US economic interests and the local elite.

As Stephen Streeter, professor of history at McMaster University, Canada, and specialist on US interventions in Central American states suggests in his seminal study, Managing the Counter Revolution 1954-1961, comparing the Guatemalan case to US-sponsored counterrevolutions in Iran, the Dominican Republic, Brazil, and Chile reveals that Washington’s efforts to roll back “communism” in Latin America and elsewhere during the Cold War represented in reality a short-term strategy to protect core American interests from the rising tide of Third World nationalism.

In Harsh Times, the military coup, brought to bear by Carlos Castillo Armas and buttressed by the CIA gets rid of the Jacobo Arbenz government. And behind this brutality is an enormous lie, which is passed off as a truth — that Arbenz encouraged the spread of Soviet Communism through the Americas.

In Letters to a Young Novelist, Vargas Llosa once wrote that the novel is a fictional creation. And even if there is an omniscient narrator, he or she is created, constructed and fictional. The author cannot truly appear in his own book. In our conversation, the writer spoke clearly of how an author cannot actually “appear” in the fictionalised universe: “The fictional narrator and the author can travel in mirrored universes, but there is a kind of prohibition for both their lives to combine.”

Nineteen years after he stated to me the prohibition of character and author becoming one, when he wrote Harsh Times, he wickedly tweaked that ideology. I can hear, like thousands of other readers, the character in the novel reading the story aloud in Mario Vargas Llosa’s voice. There is a visceral reality and fictionality in the merging together of Mario the omniscient narrator in Harsh Times and Mario the author.

Echoing Hayden White, the great historian and theorist, who also wrote in the 60s and who propounded the theory that history is fiction and fiction is history, Vargas Llosa posits that: “History and literature, truth and falsehood, reality and fiction mingle in these texts in a way that is often inextricable. The thin demarcation line that separates one from the other frequently fades away so that both worlds are entwined in a completeness, which the more ambiguous it is the more seductive it becomes because the likely and the unlikely in it seem to be part of the same substance.”

Julie Banerjee Mehta

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Kolkata and teaches Masters English at Loreto College.