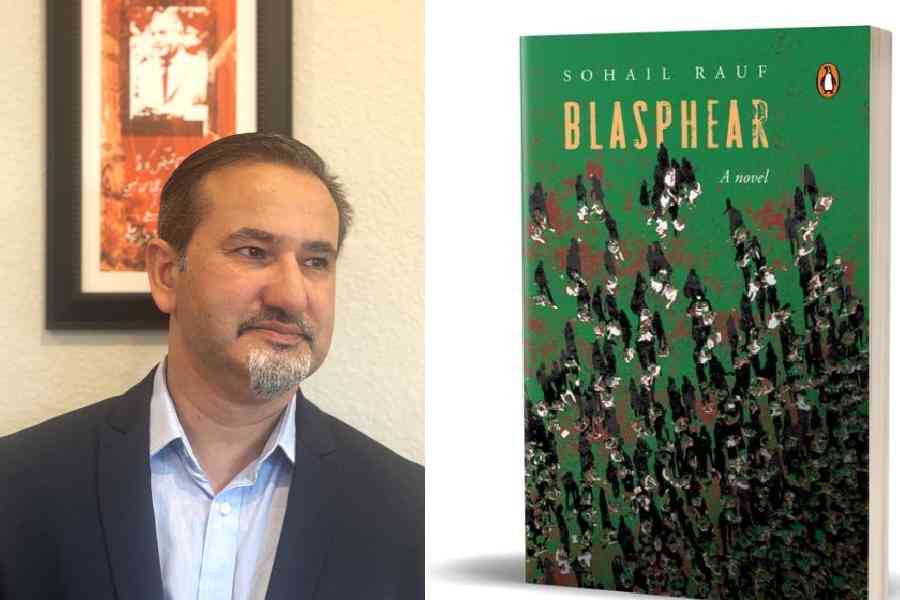

Sohail Rauf draws affirmation when he says he considers the violation of human rights in the name of religion as the ugliest form of manipulation. While the population at large chooses to be a mute spectator of this manipulation under the stringent blasphemy law and the animal-like instinct of a crowd lacking any rationale, the engineer-turned-writer talks about it. In his debut novel, Blasphear, devised from the words ‘blasphemy’ and ‘fear’, the Pakistan-born and US-based Rauf who always had a knack for writing, spins a page-turner, set in Pakistan, that starts with a case of apparent suicide investigation, unravelling the rigid and narrow functioning of religious groups destroying friendships, spreading animosity, and paralysing society. A t2oS interview with Rauf.

Blasphear connects at so many levels to a reader outside of Pakistan. The theme of religious bigotry, the dominance of the majority over the minority, religious fundamentalism, and more. What was your intention in writing the book?

I find the usurpation of human rights in the name of religious sanctity extremely repugnant. It is probably the ugliest form of manipulation. According to one report by the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, more than 2,100 people have been charged under the blasphemy laws in Pakistan since 1987, with 40 on death row and another 89 killed by vigilantes or mobs. Many of them are ostensibly wrongly accused. For me, another worrying aspect of this sorry state is that people are either afraid of talking about the issue or they brush it aside, saying that this is not religion. Well, yes, this is not religion but some people are using religion to further their agenda and the least we can do is to talk about it. This is what motivated me to write this novel.

You have been an engineer for three decades, what prompted you to explore the literary world?

I have been writing short stories in English and Urdu ever since I was a teenager. Some of them were published. Literature has always been my number-one passion. But as Faiz Ahmed Faiz says, the worries of earning are more bewitching than love. To survive as a writer, you have to have another source of earning unless you are as good as Stephen King. This is not to suggest that electrical engineering feels like a chore to me. In fact, for me the charms of signal-processing engineering are not far behind those of literature. When I was a kid, I wanted to be a scientist and a writer. I think with a PhD in signal processing and this novel, I have realised both dreams and I’m loving both.

Is the book a work of pure fiction or are there some realities to the stories? Are the characters of Mohan, Ram, Furqan and Hasan inspired by any real-life persons?

Real-life blasphemy-related incidents inspired me to write this novel. But this work is entirely a product of my imagination. Although like most authors, I have borrowed traits of living people, including my own. Furqan is a bit like me, an introvert and an idealist. Hasan to some extent takes after a friend of mine.

Tell us about building the titular character of Waqas, the inspector investigating the case.

Waqas’s fixation with his failures is what I was aiming to depict. I wanted to show him as a person stuck in the past. He is a very nostalgic person; memories intervene amid his day-to-day work. He wants to undertake a brave thing, tread where not many want to go, but he feels he is not up to the task. He is haunted by his failures.

Religious fundamentalism has been a scourge in every society and that is what we see in your book. You left Pakistan and have settled abroad. The incidents that push the story in the book and similar ones keep making headlines and seem contemporary. What is your view on that?

I think religion, besides being a source of solace and hope for mankind, can unfortunately be a tool of exploitation also. As I said above, Pakistan has seen countless incidents of the blasphemy law exploited by people to meet their evil designs. India has had its own share of religious-minded people playing into the hands of politicians. We have seen a US Congressman asking Columbia University’s president, as part of the investigation into pro-Palestine protests, if she wanted the university to be cursed by God; I could not believe what I was hearing. I think all religions, as a package, must have compassion, tolerance and rationality, if we have to stop them from being exploited.

The book has a poetic flavour as well. You start off with Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s poetry and then move on to Meeraji. Meeraji, in fact, becomes a part of the book. How much have they influenced you?

One key message I want readers to take away from the novel is that poetry (and art) can provide that unifying force that sadly has been missing in religions or whatever religions have morphed into. Therefore, poetry is an important element in the story. I have also tried to portray Meeraji as a symbol of a misunderstood artist. Like Manto, he has been known more for his outrageously obscene poetry, whereas the real genius that he was is conveniently forgotten. Nasir Abbas Nayyar’s book on Meeraji helped me understand his modernist poetry and I found that some of his themes are relevant to my novel.

Who have been your literary influences?

Faiz Ahmed Faiz, I’d say, has been the biggest influence. I’m not a poet so I can’t say he influenced my writing, but his fearless idealism and resistance poetry have inspired me, as they have inspired so many others. I admire George Orwell for his strong political messages delivered in simple, elegant yet hard-hitting prose, which I want to emulate. I also mimicked Arundhati Roy’s style of quoting Urdu poetry in English fiction. In Urdu fiction, I have been a fan of Abdullah Hussain’s bold exploration of socio-political themes.

Post Blasphear, what can we expect from your pen?

I am working on a military legal thriller about the Baloch insurgency with a bit of espionage. I am waiting for feedback from some friends who know Balochistan better than I do. I hope the book will be ready by the end of the year.