Parsis celebrate New Year (Jamshedji Navroz) on March 21. Now hardly five months later we are celebrating New Year again!

As a community we love to argue and the story goes that if there is no one to argue with we will happily argue with our reflection in the mirror.

The calendar controversy is the story behind the many New Years, and it unfolds from the time of King Jamshed, whose birthday was celebrated on the day of the solar equinox, March 21. This day was celebrated as Nav (New) Roz (Day).

Ancient Zoroastrians observed a 360-day calendar. When the Sasanian King Ardeshir I ascended the throne, he changed the 360-day calendar by adding 5 extra days dedicated to the Gathas of Zarathustra (ancient Avesta texts attributed to be the words of prophet Zarathushtra). This Zoroastrian Calendar uses the suffix Y.Z. (Yazdegerddi era) indicating the number of years since the coronation of King Yazdegerd III in 632 AD.

But a solar calendar is 365 and a quarter days. Hence, the solar calendar and the Zoroastrian calendar began to diverge.

In 1096, the Solar calendar and the Zoroastrian calendar coincided. It was resolved that every 120 years an extra month would be added. This calendar was called the Shenshai or Imperial calendar. But in the course of several years (120), this was forgotten and the New Year which was supposed to be celebrated on March 21 is today being celebrated on August 16.

Now the fun begins.

The Parsis of India added the extra month only once, in 1096 CE. But the Parsis in Iran did not. In 1720, a priest from Iran, Vilaiti Jamaspi, came to India and discovered there was a month’s difference in the two calendars. A number of Parsis decided to follow the Iranian calendar which was called the Kadmi calendar.

So now we have three New Years.

Jamshedji Navroz on March 21.

Kadmi New Year (floating date) on July 16.

And, Shenshai New Year (floating date) is on August 16.

[Read here for more]

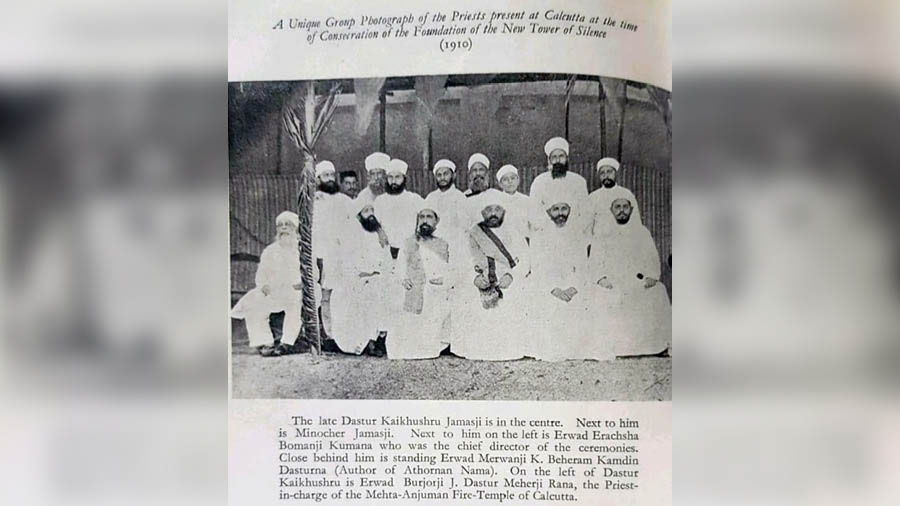

The Kadmi and Shenshai priests consecrating The Tower of Silence in Kolkata, 1910

Five days before New Year are the Gatha days and we also call them the Muktad days or Farvadegan. We believe that on these days the Farvashis or guardian angels of our ancestors come down to earth and are welcomed by us with prayers, flowers and food. The Farvashis bless us and wish us happiness in our homes and families. These are days to remember our ancestors.

We Zoroastrians never lose any opportunity to celebrate. As we say, “khao, peeyo, ne majha karo (eat, drink and have fun)”.

We are a small (360 members) ageing community in Kolkata. Around 220 of us are over the age of 60 and only 33 children are under the age of 20. However, memories of Navroz of our old and young revolve around the community, enjoying an evening of entertainment and, of course, dinner which must have GPD, that is Gos Pulao Dal, and Patri ni Machi (fish wrapped in banana leaf), Salli Marghi and Lagan nu Custard.

Of new clothes, a visit to the Agiari (fire temple) and the century-old ‘natak’ tradition

Across generations, for both Zenobia Dalal and (right) Dravasp Meherji, the ‘natak’ is a primary part of the celebrations. The Calcutta Parsi Amateur Dramatic Club has maintained its tradition of performing a Gujarati play free of charge for the community for over a 100 years

My aunt, who is closing into her century, recalls the nataks (play) at the Corinthian Theatre where Byron’s drinks were free for all, and the children got a slab of chocolate. She remembers that there were no women acting at that time, and the men would play the women’s parts. My uncle, Homi Jila, being short in stature, would always be a girl in the play. Aunty says, it was always a full house and a noisy happy audience.

My young friend Dravasp Meherji writes that on Navroz day, he garlands the pictures of his ancestors and then visits the fire temple. He enjoys the chasni (consecrated food) and the breakfast laid out for the community. More than anything he loves Sev (vermicelli pudding) which they make at home. Then relax in the afternoon and off to the Gujarati Natak followed by dinner. “That’s how I spend my Navroz every year,” he shares.

For Raizan Vatcha, Navroz means being with friends and family. “How such a small group of people have had such a huge impact on my life is an extremely humbling experience,” he tells me. Yes, as a community, we are very close. The centre of the community is the Calcutta Parsee Club in the Maidan where we meet to play and socialise as often as it is possible.

Zenobia Dalal, a much-loved teacher of Pratt Memorial School, recalls, “Navroz meant new clothes, the mandatory Agiari (fire temple) visit, meeting friends… but most important was the natak with its race for seats, packets of sweets and cold drinks.” Today, she is in her seventies and the chanting of prayers, hugs and wishes of friends once again recreate the unique magic of Navroz. Some enjoyments never change. Our Calcutta Parsi Amateur Dramatic Club has maintained its tradition of performing a Gujarati play free of charge for the community for over a hundred years. As a Calcutta Parsi, it’s a day that stands out months ahead in the calendar.

‘Khao, peeyo, ne majha karo!’

‘Navroz to me is all about the smell of fresh flowers and prayers in the morning,’ shares Tehnaz Punwani. For (right) Cyrus Confectioner, it is a day to ‘forgive and start afresh’

It’s a day to be with family and friends and a day to forgive and start afresh to leave all bitterness and bad thoughts and words behind, says Cyrus Confectioner. Pray for forgiveness and at the end of the day, sit with family and friends and have a few drinks and a hearty tasty meal.

Ratan Postwalla, the young and dashing trustee of our agiari says that Navroz is one of those days “when I feel unquestionably Parsi”. “The day begins with a community prayer at the agiari. More than the significance of the ceremony, I look forward to the breakfast right after because that’s where we meet and wish each other and truly feel like it’s the start of a special day.” After a large family lunch, a tradition started by his mother, he rushes off to prepare for the evening natak where he is always the lead performer. The day ends with a large group of friends drinking several cups of tea at the Russel Street Punjabi Dhaba.

Aban Confectioner recalls that Navroz would always start with new clothes and a small gift made lovingly by her mom, our universal Arni aunty. Then it was meet-and-greet time at the agiari followed by doing the ‘relative rounds’ meeting close family. Lunch would be granny’s super amazing mutton pulao and large jalebis and sutarfeni (sweet made out of vermicelli). Evenings were for the natak and chatting, hardly aware of anything happening on stage. (Our youngsters today can be seen at the natak today doing exactly this). It was always a special day of being a Parsi and part of a community.

Tehnaz Punwani, our newly-elected first lady trustee writes, “Navroz to me is all about the smell of fresh flowers and prayers in the morning — starting with either sev or ravo or mitthoo dahi for breakfast, prawn patio for lunch and chicken pulao for dinner. Yummm! Yes, Navroz, for me, also means feasting with my favourites. Navroz for me is also having a jolly good laugh at the annual natak – either watching it or acting in it and of course meeting friends and family and wishing everyone the very best for the day and the years to come.”

The spirit of embracing change and growth

Young Yasna Buchia looks forward to going to the ‘natak’ in the evening followed by dinner with family and friends at the OMT Hall. (Right) Samara Mehta Vyas is excited about the stories from Granny, lighting ‘divo’ and ‘tilli’ time

Navroz signifies the importance of embracing change, honouring heritage, and embracing the positivity that accompanies new beginnings. Young Yasna Buchia writes, “Navroz is the one festival that I always look forward to. I’ve made so many memories… going to the natak in the evening followed by dinner with family and friends at the OMT Hall. Navroz embodies the spirit of embracing change and growth. Navroz prompts us to shed the past, embrace new beginnings, and foster connections with loved ones.”

At my granddaughter Samara Mehta Vyas’ home, the house is decorated with flowers and a special garland (toran) is placed on the front door. ‘Chalk’ is then put on the floor outside the door and everyone enjoys making different designs (rangoli). It’s a fun traditional bonding time. “On a holiday just before Navroz, we light divos (diyas) in front of the pictures of our loved ones who are no longer with us. Then Granny makes us all tell our favourite stories about our dear departed and they are remembered with lots of love. It makes me sad and also happy. On Navroz, Papa makes us say a prayer, we all light a divo and then it’s tilli time and all of us are garlanded and we get a tilli (tika) on our forehead and rice is put on the tilli with a blessing of ‘Ghanna sal jeevi ne ghanoo ghanoo sukh joojo ji’. (Live a long and happy life). Then everyone will inspect the forehead to see how many grains of rice are stuck to see how many children we will have — each grain denotes one child as per the legend. In the evening, we wear our new clothes and go to the natak and go to 52 Chowringhee for dinner,” she tells me with gusto.

Who is a Parsi?

Navjote ceremony of Mehta's three grandchildren

I quote from Mr Fali Nariman’s foreword in Who is a Parsi?

‘What today keeps this small and diminishing body of persons together is a faith that does not demand too much from its adherents: somewhat reminiscent of the Chief of Protocol, who had accompanied the then Queen of the Belgians on her visit to Warsaw in the nineteen hundred and fifties; it was at a time when Poland was still dominated by the Soviets. The Belgian Queen was a deeply religious person, and the Chief of Protocol was assigned to accompany her to Mass on Sunday.

“Are you a Catholic?” the Queen asked him.

“Believing, but not seriously practising, Your Majesty”, the Protocol truly replied.

“Of course,” the Queen said, “then in that case you must be a Communist.”

“Practising, but not seriously believing” was his frank reply. We are like that Polish Functionary. Most of us are believing, not truly practising Zoroastrians. Belief in the faith is what loosely keeps us all together. It is the social interaction which binds us close together.

Hence the importance of the traditional natak and dinner organised each year by our Calcutta Parsi Amateur Dramatic Club. They put in a tremendous amount of time and effort to make this performance. Their reward, in a manner of speaking, is being an institution that binds the entire community in rejoicing and celebrating together on a very special day.’