At a time when furniture was mostly straight lines, the iconic American sculptor-woodworker of the 20th century, Wharton Esherick, found comfort in flowing forms that captured the beauty of nature. That left an indelible mark on modern furniture designers.

Even though Esherick was a well-known name in woodworking and furniture circles, he remains sort of a hidden gem for most of America, let alone the world. It’s like people don’t know about things in their own backyard.

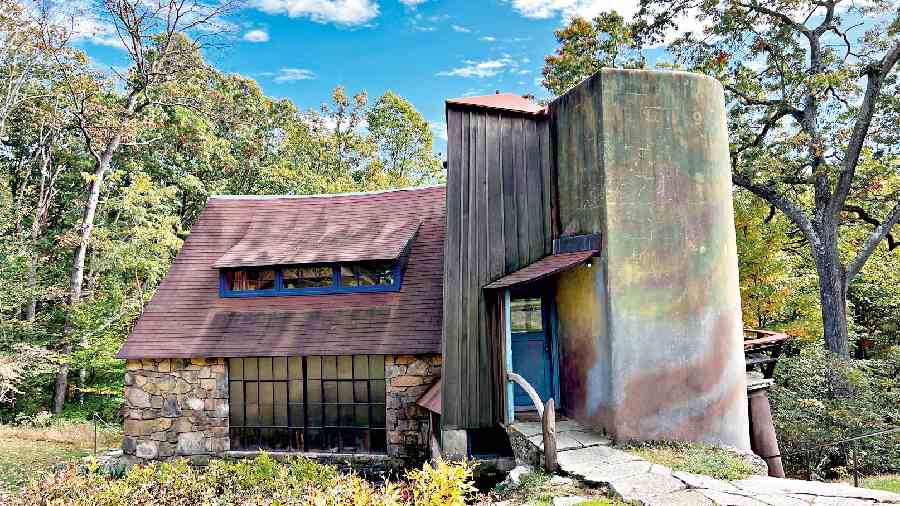

About an hour’s drive from Philadelphia brings those curious about architecture and designing to the Wharton Esherick Museum in Horseshoe Trail, Malvern, cutting through beautiful village scenes, especially when autumn is in its full glory.

Getting lost in nature

Esherick remains among the most influential in American furniture design. It’s just that he wasn’t making designs that were sent off to manufacturers who could make thousands of it. He was an artist who was making one piece at a time.

A few designs by Wharton Esherick

Born in 1887 and died in 1970, he was part of a generation that left the big city life to live amongst nature. Esherick and his wife Letty found a ticket out of Philadelphia to a place that was once mostly deserted. It was back to nature in every sense. In no time, they were growing their own food, leading a very bohemian life. Letty did a lot of dancing and weaving while Esherick was painting at the time. That’s one of the most interesting aspects of his design. He studied fine arts and he took that knowledge to furniture designing and architecture… things he didn’t study.

Small sculptures like ‘The Race’ were among the first three-dimensional objects Esherick made after his initial experimentation with carving wood for frames and printing blocks

His early career days were dedicated to that of a painter and book illustrator. In 1910 he came across Henry David Thoreau’s book Walden, which became his inspiration. In the footsteps of Thoreau, he moved to the country and bought a farmhouse on a wooded hillside to lead a simple life.

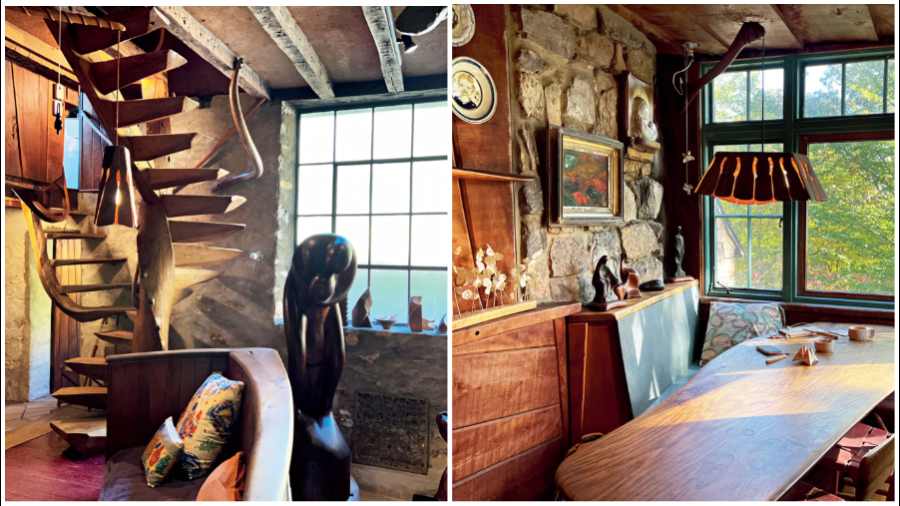

(Left) The twisting spiral staircase draws much of its impact from a series of cantilevered steps supported by tenons mortised into a central column; the steps seem to float, lending the staircase a seeming precarity despite its sturdy construction. (Right) The kitchen space at Esherick’s studio/home

It was only in the 1920s that he developed an interest in wood. He perhaps looked at the entire exercise from the perspective of a sculptor. The designs he came up with always had an element of fun. “If you take the fun away I don’t want anything to do with it,” he said.

His passion for woodwork came at a time when furniture was typically defined by its use and to consider it as sculpture was a breakthrough. He used the material most readily available — wood — and employed the hand tools of the wood-carver and carpenter. In 1926 he started building a new studio and filled it with his own furniture. His first new furniture was “influenced by cubism and German Expressionism”. By 1928 he had built a five-sided table with splayed legs, the top pieced together from tapered planks. A set of chairs had backs carved into facets, with triangular openings. He was practical and so each chair has a “cutout underneath the crest rail so it could be lifted easily”. He soon received commissions, like from judge Curtis Bok.

(Left) Inside Wharton Esherick’s studio. (Right) Drop Leaf Desk (it looks like a cupboard but it can be opened up) features representational surface decoration, or “literature”, that links Esherick directly to the arts and crafts movement although it was the last piece of furniture he made in that style

Once he took up designing furniture, it was a life dedicated to chairs, desks, tables, bookcases and what not. Like social reformer and architect Rudolf Steiner, whose books had a deep impact on Esherick’s outlook, there was emphasis on curves.

A mention needs to be made of the wood chisels he bought around 1920 to carve frames for his paintings, acquainting him with the magic wood offered. This was also the time he was perhaps not happy with his paintings because he was still looking for his creative identity. Wood was like playing in the park. He didn’t study woodwork, so his understanding wasn’t stuck within a frame.

Living among curves

He believed that humans were not born into a world of rectangular things, so why live in those. Let’s live among curving shapes, he wanted to say. Furniture to him was like sculpture that had a practical purpose. No wonder, a spiral stair or a free-form table were the results of his imagination.

His studio-home is in itself a marvel. Started in the 1920s and gradually developed over the decades, it grew organically, accommodating the artist’s needs.

The object that highlights his approach to furniture the best is a staircase he built in 1930. It ascended from the studio space in his new building to living quarters on the second floor. He carved a tree trunk into a twisted sculptural form, to which he attached prismatic steps in a spiral. The staircase was removed from his studio for display at the New York World’s Fair in 1939-40.

Browsing through an old issue of American Woodworker, one gets a fair idea of the process he employed. He always considered the proposed location for his woodwork. The article notes that before making a commissioned dining table, for instance, Esherick would lay paper on his client’s floor, sketched a tentative outline on it, and then asked family members to sit and move around it. When satisfied that it suited the spatial context and traffic flow, he would roll up the sketch and go home to select the boards from his woodshed.

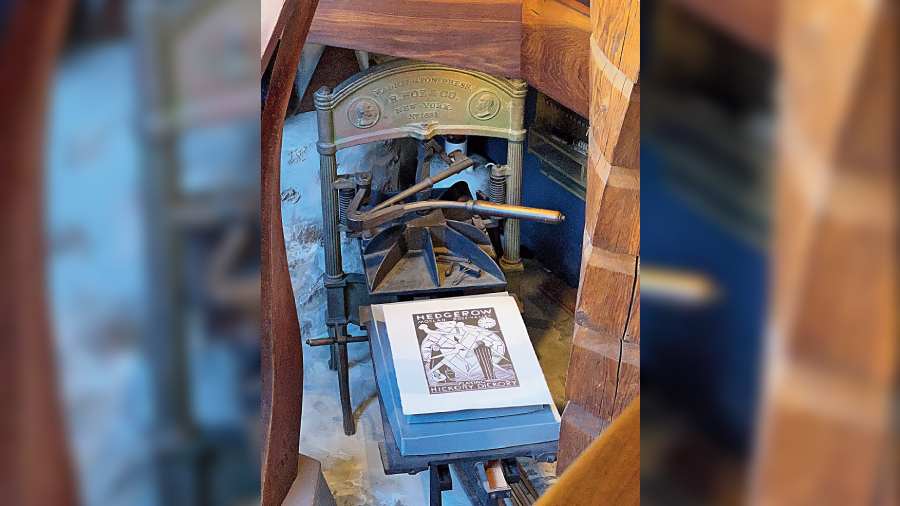

Printmaking was a pivotal medium for Esherick, providing him the freedom and experimentation he had not felt as a painter, and a window into working with wood

Equally interesting are the finishes he employed. When he was making his early pieces, he used a mixture of boiled linseed oil, turpentine, and beeswax, which had to be applied at a very critical temperature. The technique changed over the years.

Whatever he did was for the sake of art and not always money. “He rarely made any money,” Mansfield Bascom, Esherick’s son-in-law, wrote in the biography Wharton Esherick: The Journey of a Creative Mind. “He refused to talk about his art, or any art. He thought artists only made fools of themselves doing that,” Bascom wrote.

‘Dean of American Craftsmen’

Esherick’s work had a three-dimensional effect and a meticulous attention to detail. Sadly, his approach to woodwork died with the man himself as he rarely accepted apprentices. What he left behind has been worthy of praise from greats like Sam Maloof and Wendell Castle.

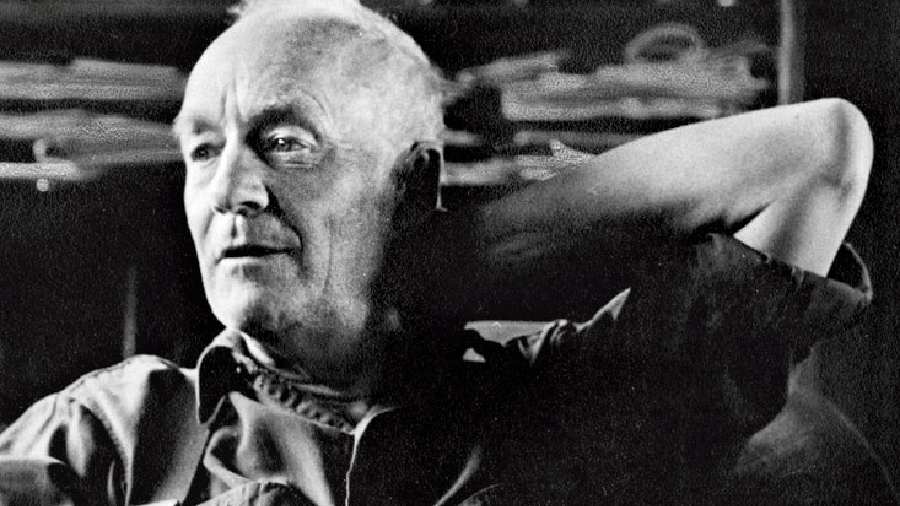

Painter and designer Wharton Esherick Picture: Susan Sherman

In a way, he had an influence on another legend — the architect Joseph Esherick, who sort of apprenticed with his uncle. The architect believed that buildings should be designed from the inside out and said: “Beauty is a byproduct of solving problems correctly.” Reading those words, one can’t help but remember Wharton Esherick’s approach.

Returning to the museum, it’s surprising to find out that Esherick made exceptional designs using mostly hand tools and only later in his life did he use a bandsaw built with bicycle wheels. By the time he passed away in 1970, Esherick was heralded by the national art and design community as the ‘Dean of American Craftsmen’.Going through his studio and house one can’t help but wonder how he led the movement to re-establish the value of hand craftsmanship. He did and the world is grateful for it.