Often at night, I comfort my body. With gentle words and caresses, I make it smile and put it to sleep. There are two of us in the room now, me and my body,” says Delhi-based artist Anjum Singh, whose show of drawings, watercolours and oils titled “I am still here” announces a relationship which is often unpredictable but always finds its centre.

Singh’s time as caregiver to her body started in 2014, when she was diagnosed with cancer. The artist had studied the human figure as a student in Santiniketan and Delhi, but now makes its complex internal universe, the object of her gaze. A universe with its own network of demands and supply which was revealed to Singh as she navigated hospitals, doctors, investigations and surgeries over the next five years. “Throughout this period, I was closely observing. The machines, instruments, medical reports, test slides and more, all mapping the human anatomy and monitoring its ebb and flow fascinated me, even though I felt trapped by them.”

From here, the artist went on to construct a storyline which tries to make sense of the body in many different ways. “It’s been a deeply personal journey, marked equally by a strong feeling of detachment,” says Singh.

Body art: Exhibits from cancer survivor and artist Anjum Singh’s exhibition Shikha Trivedy

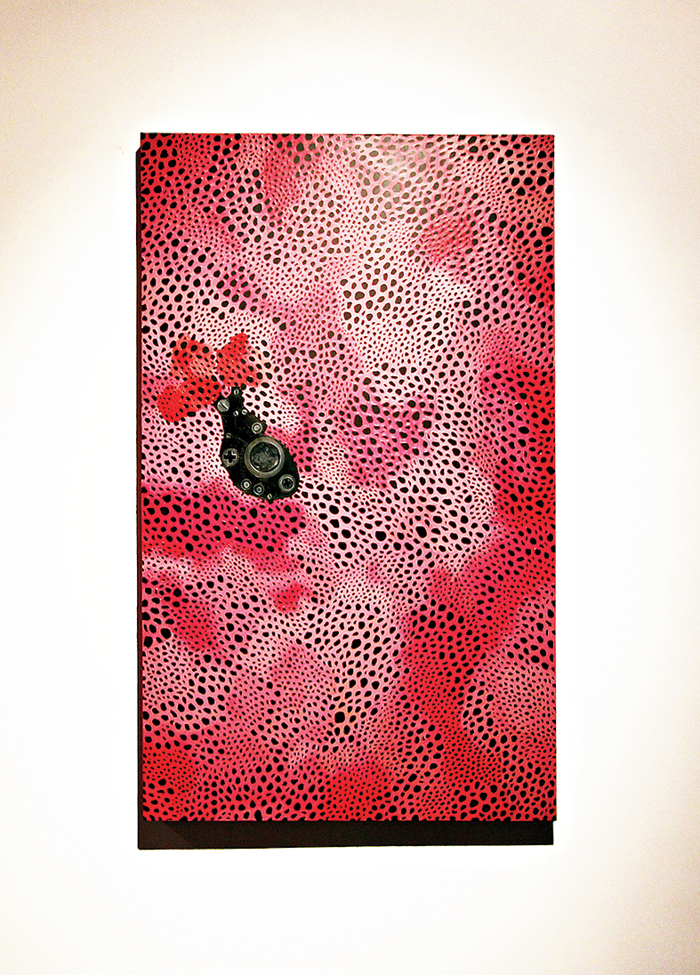

Some images speak directly to the viewer; a roll call of preening organs in My Body Candy Floss, a group of ethereal cells floating beneath the skin’s surface in Skin. But in Broken, asymmetrical patches in sinister black are bits and pieces of the heart, torn from the body by the artist and then randomly put back as separate entities. Creating an uneasiness which dissolves in the Heart Machine where a mesh of cheerful pink cells fill up the canvas. “The heart continues to beat and remains deeply in love with life. But on the other hand, it is just another gadget. I had fun doing these paintings, specially Broken,” says Singh, who has always liked to mix the organic with the artificial in her visual narrative.

A few works carry traces of the turbulence in Singh’s situation — the deliberate, almost angry strokes of a black pencil zigzag their way across the paper when the body becomes the site of contestation between medicine and the artist. But she is adamant, they do not define the show. The liberal use of startling reds and pretty pinks in Belly Button come simply from her love of these colours and have no hidden meanings. “For me, Belly Button is all about the sheer joy of finding the right shade of red after hours and days of searching. The pleasure of making art and nothing more.”

The show builds on the artist’s career-long exploration of chaos in a city and the manner in which an individual criss-crosses its emotionally and physically fractured spaces. Where the yearning for order can be the most fragile obsession. In “I am still here” — the first words spoken by Singh on waking up one morning after a very dark night — she finds some of that elusive calm. The energy and movement infusing the works show no urgency in getting anywhere or proving a point.

“I am still here” is many things at the same time — disturbing, bold, moody, reflective and playful — but mostly a life affirming experience.