The phone call came in the early hours of December 15, 2020. It was human rights activist Kamal Chakraborty on the other end with the news of the death of Chandradhar Das, a 104-year-old resident of southern Assam’s Cachar district. Das had died of a heart attack. Chakraborty, who had been fighting for Das’s right to be an Indian for the last few years, said, “He died stateless. We failed to fulfil his last wish. He couldn’t die an Indian.”

For the last two years of his life, Das had remained a doubtful or D-voter. I hadn’t heard of the term until I visited Silchar, a city 340 kilometres southeast of Guwahati, three years ago. It was months before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections and the BJP had revived the spectre of the National Register of Citizens or NRC in Assam; the state was in roil. There were over a lakh D-voters who had no place in the NRC, no right to vote and were considered foreigners. Many of them — women, children and the elderly — had been thrown into detention camps.

Soon after that trip I met Chakraborty, who is the chief convener of a group called Unconditional Citizenship Demand Forum, in Calcutta. That day, he was carrying a long list of detainees. “Most of these are marginalised people — rickshaw pullers, domestic helps, daily wage labourers, farm hands,” he had explained. In many cases, frequent floods had wiped out property and other documents. “Usually unlettered, these people can neither appeal nor do they have the proper papers to prove citizenship,” he had added.

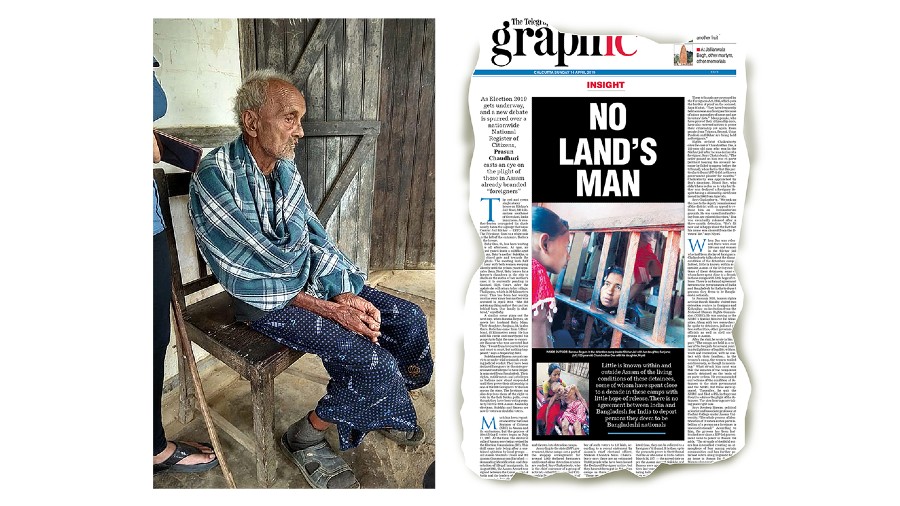

Among the sheaves of documents Chakraborty was carrying, there was one that caught my eye. It had a photograph attached, of a frail old man held up by a middle-aged woman. The man in the picture was Das, who was 102 then, and the woman was his daughter Niyati Roy.

“The authorities put Das in Silchar jail without hearing his account because he failed to appear before the foreigners’ tribunal,” Chakraborty had told me. Roy had reached out to Chakraborty for help. Her father had a citizenship certificate issued in 1966 from Agartala; she had no clue why he had been declared a foreigner. “We took the case to the deputy commissioner of Silchar district with an appeal to release Das on humanitarian grounds. He was unwell and suffering from age-related disorders,” Chakraborty had said. Das was eventually granted bail after a three-month detention.

The day I called up Chandradhar Das, he had sounded dispirited. It was the April of 2019. He had been born with a cleft lip and his voice over the phone was muffled, his accent difficult to decode. Even then this is what I could gather: “They put me in jail... for 80 days... but you know I have a citizen card... we had to flee to Agartala from [East] Pakistan before the 1965 war.” His voice drowned in tears. Roy repeated the rest of what he said — “I just want to die an Indian.” His wife Adarmani, who is in her 90s, added that her husband was convinced that Prime Minister Narendra Modi would grant them Indian citizenship.

On February 22, 2014, the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate, Narendra Modi, had promised at an election rally in Silchar, “As soon as we come to power at the Centre, detention camps housing Hindu migrants from Bangladesh will be destroyed.” He had also advocated the removal of the “D” tag against 1.43 lakh voters in Assam. Thousands of Bengali Hindus applauded him that day and the speech was recorded and widely shared. Das could not go to the rally but watched the video of the speech on a loop on his son Gauranga’s smartphone. Says Roy, “It was a kind of an obsession. He would watch the video again and again.” According to her, for Das, “Modi Baba” was an “incarnation of god” and he was sure he would help him prove his Indian citizenship.

Das had settled in Teliamura in west Tripura in 1965 after fleeing Comilla in East Pakistan, now in Bangladesh. He worked as a daily wager; from being a mason’s assistant to selling vegetables, he had done it all. His three children, a son and two daughters, were born in India. A few years later, he migrated to Silchar in Assam.

In the village of Baraibasti in the Amraghat area, he started farming vegetables and would sell them locally. They were poor but not so their quality of life. Das married off his daughters and Gauranga got a peon’s job in a bank. He did not harbour any doubts about his citizenship as he possessed a certificate of registration that clearly identified him as an Indian citizen according to the Citizenship Act of 1955. A copy of the certificate issued to him at Agartala by a registration officer in 1966 is in the possession of The Telegraph. Das clearly made Assam his home long before March 25, 1971, the cut-off date for detection and deportation of foreigners in Assam, as per the 1985 Assam Accord or Section 6A of the Citizenship Act of 1955. Das and his family members never faced any problems acquiring other identity documents such as ration cards, voter cards, PAN cards and even Aadhaar cards. All adult family members in the household had religiously cast their votes in state and general elections until 2019, when their names went missing from the electoral rolls.

The trouble, however, had started two years before that. In May 2017, all of a sudden, Assam Police asked for documents to prove that he arrived in India before 1971; they suspected that the centenarian was an illegal migrant from Bangladesh. The SP of Cachar forwarded his case to a foreigners’ tribunal, one of 100 semi-judicial bodies that determine whether a person staying illegally in India is a foreigner or not. Human rights organisations and lawyers have claimed in the past that these tribunals deny people citizenship for spelling mistakes in names, inability to provide detailed documents or recall minute ancestral details dating back 50 years or more.

The tribunal served a notice on Das, directing him to offer a written statement and submit documents to prove his citizenship. He was served four more notices. But neither Das nor his family members had any clue about how to handle the situation. Das suffered from dementia and age-related disorders. The family’s request for adjournment of the case on the grounds of Das’s ill health was turned down; it was said that they couldn’t furnish a proper medical certificate. In January 2018, the tribunal declared him an illegal migrant and an order was issued to delete his name from the electoral rolls.

Thereafter, Das was declared a D-voter and sent to a detention camp inside Silchar jail. Says Chakraborty, “The order passed on him was ex parte (without hearing his account because he failed to appear before the tribunal), when fact is that this particular tribunal (Foreign Tribunal-6) did not have a government pleader for months.” Das’s advocate Soumen Choudhury says, “His Citizenship Card, which is the base document, was issued at Agartala in 1966. When we asked the authorities at Agartala to authenticate the document, they didn’t respond.”

Even after being released from the detention camp in April 2019, Das had to visit the tribunal several times. Roy remembers her father’s distress as she ran from court to court, met advocates, social workers and politicians to clear the foreigner tag against his name. After the Citizenship (Amendment) Act or CAA was passed in Parliament in December 2019, the family rejoiced that Das would finally get his Indian citizenship. “The Act [CAA] did nothing for us. My father and all of us in the family are now foreigners in the eye of law,” said Niyati.

She cremated her father three weeks ago.